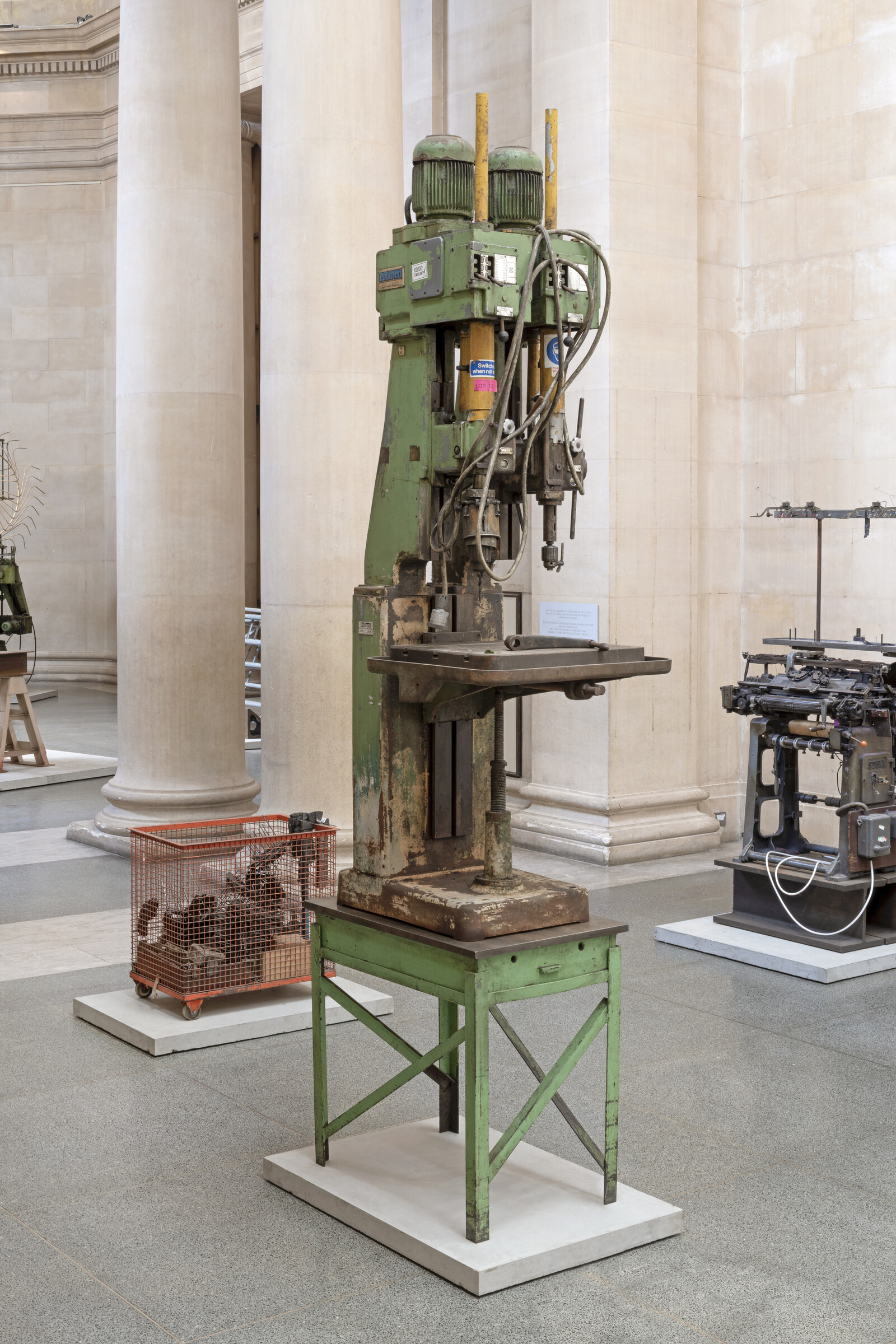

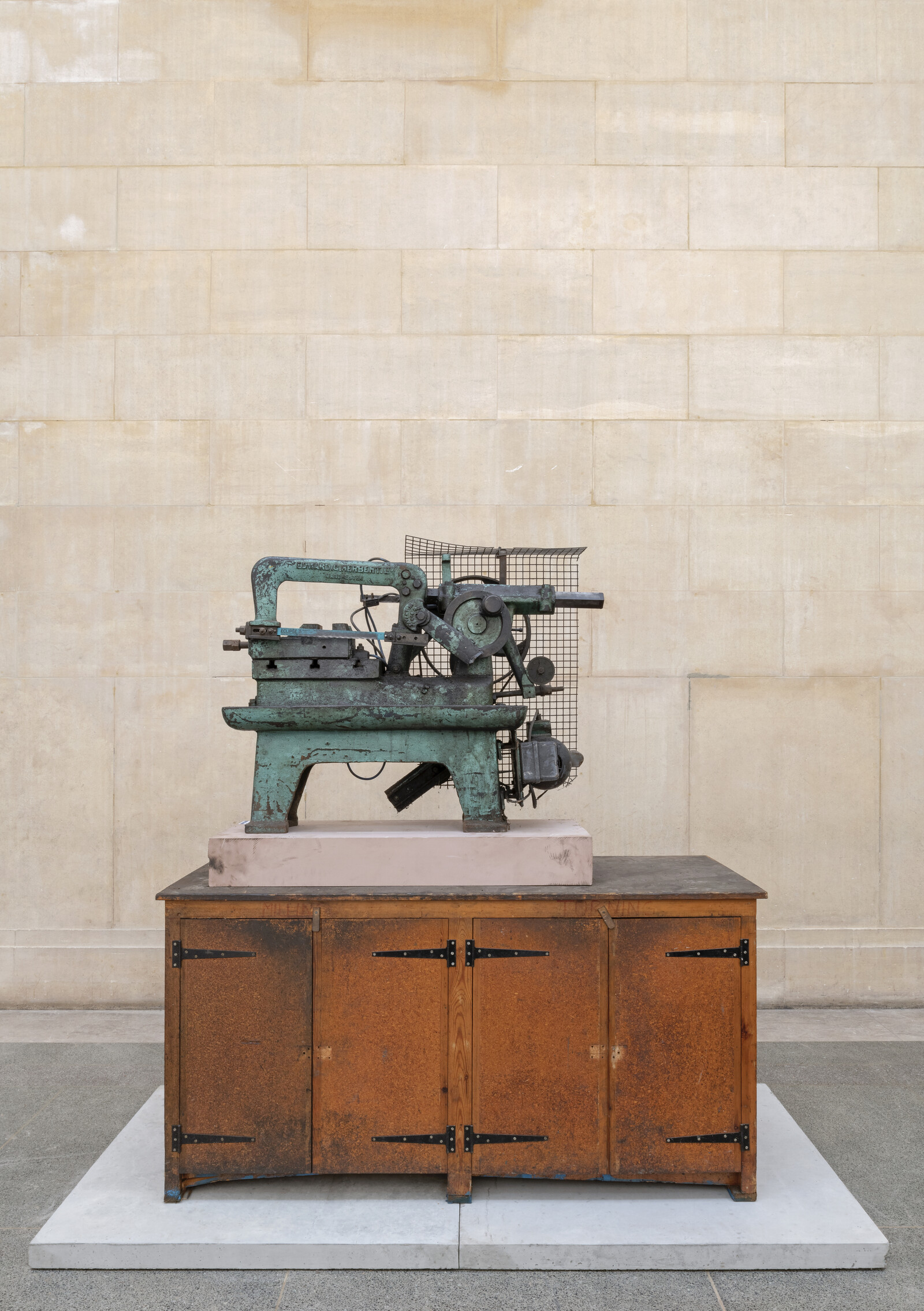

The relationship of sculpture to industry and its processes is a long one, and heroic—think of all those bronze figures emerging from armory foundries, of Marcel Duchamp and Constantin Brancusi wandering jealously through the 1912 Paris Aviation Show, of Richard Serra rolling steel at a Baltimore shipyard—but seldom is it elegiac. Such a description would however be fitting for The Asset Strippers (2019), an extraordinary installation of sculptures by Mike Nelson. The work has been assembled from machinery and industrial materials and fixtures bought from auctions disposing of the assets of UK factories, although Nelson does not simply turn the expanse of Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries into a storehouse, but rather places them in new configurations. Despite the technical difficulties of moving these massive objects—their total weight is estimated to be approximately 40–50 tons, close to the loading capacity of the gallery floor—Nelson’s touch is assuredly light. Often little more is done than stacking objects on top of each other—a cement mixer is placed high upon two wooden work benches, its drum upturned as if yearning to peer even higher—but the effect is transformative. One begins to see them not only for what they once were, but for what else they might be.

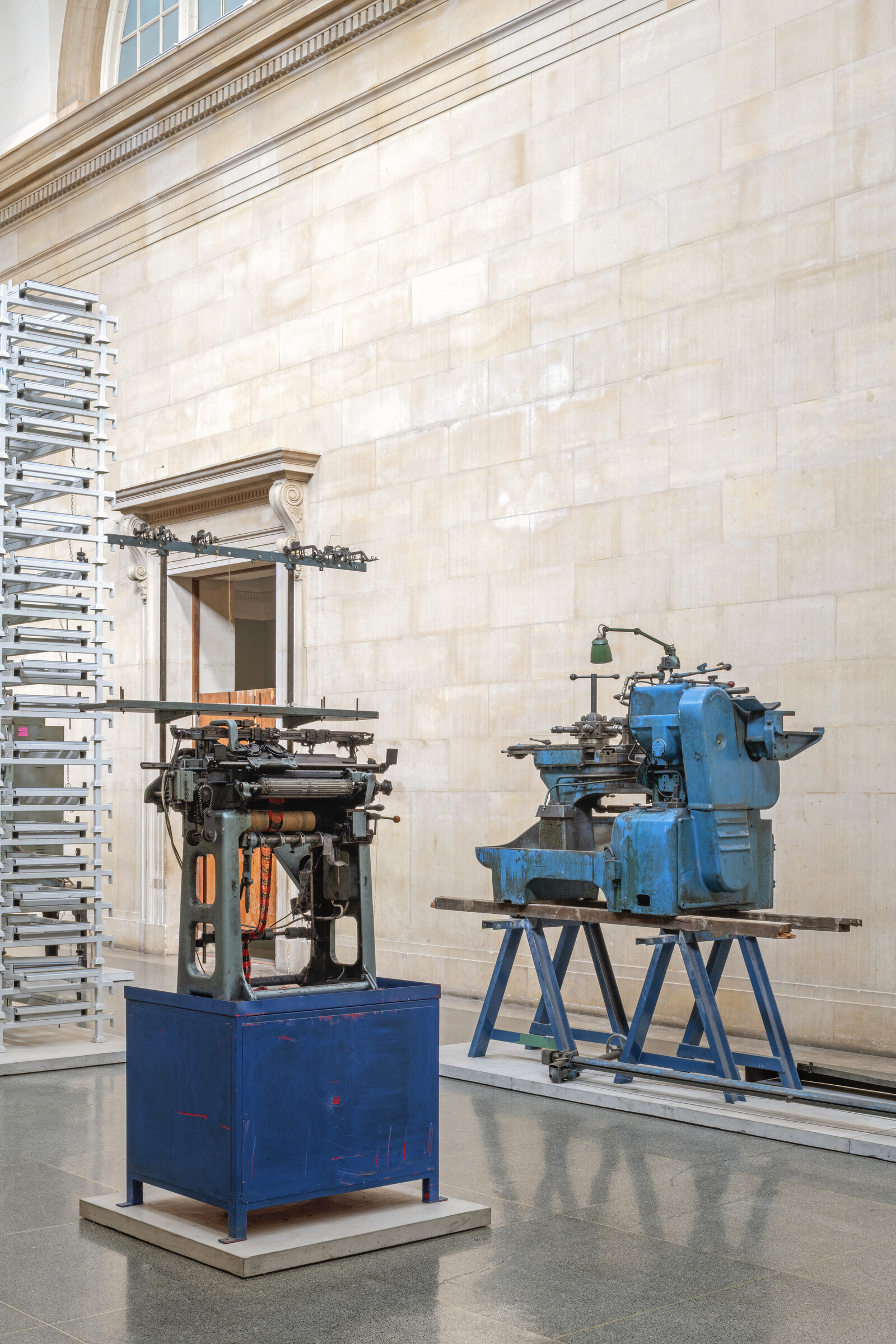

One of those things, of course, is art. Assuming one has a certain familiarity with its modern history, or at least the masculine, Anglo-American variant here evoked, one cannot help but see these artworks in relation to those that have come before. And so that cement mixer becomes an overlooked work by David Smith, its scuffed and worn pedestals derelict Ben Nicholson reliefs which have become somehow deeper; pillar drills become yet another metamorphosis of Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill (1913–16); and the four golden, circular hay rakes an apocalyptic alignment of Paul Nash’s foreboding suns. And, of course, works by Anthony Caro seem to come together out of the corner of one’s eye, often only to disperse again when looked at more directly, although a Prussian blue assemblage of lathe, trestles, rails, and panel best maintains the languid poise of some of the sculptor’s most celebrated mid-1960s works.

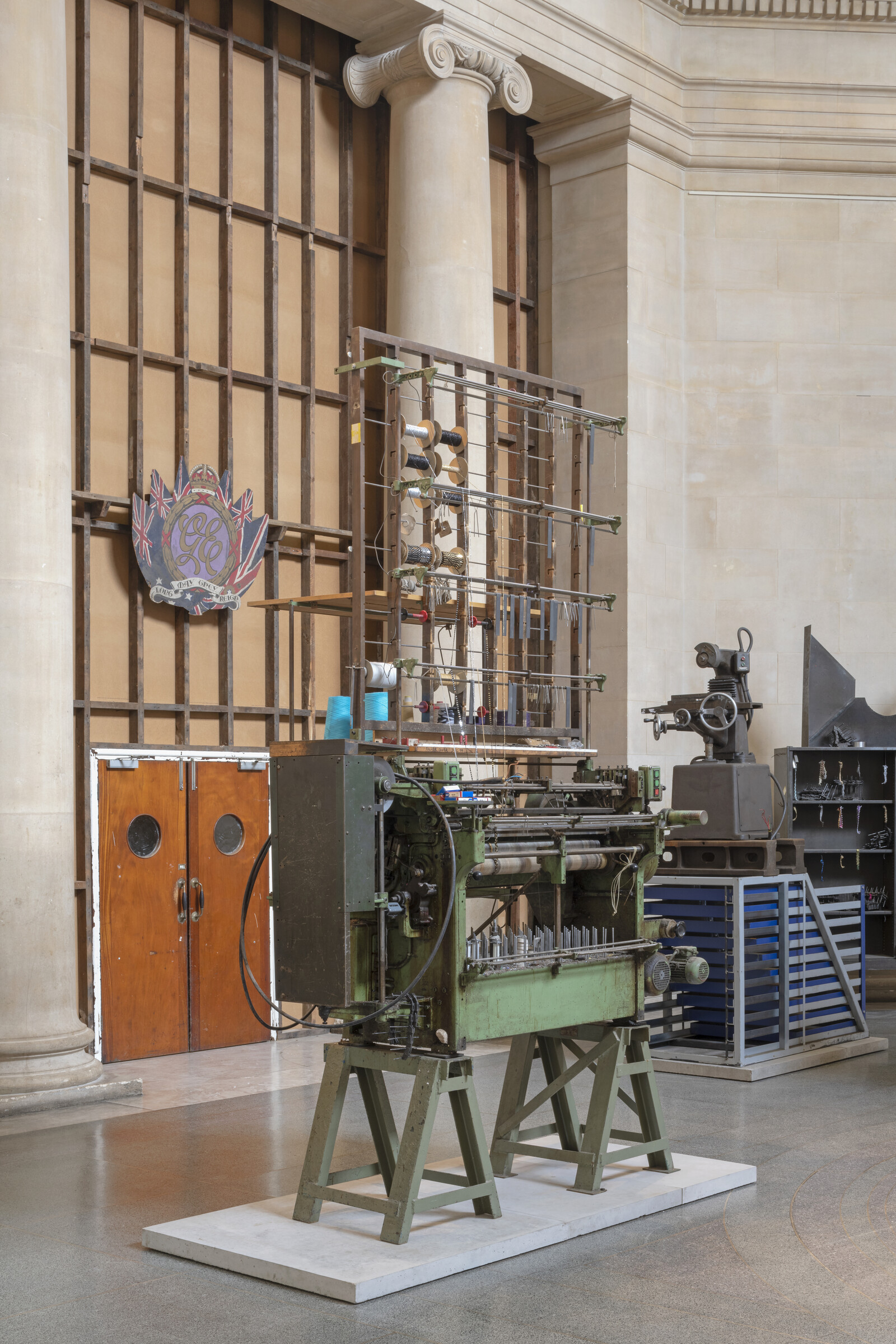

There is a pleasure to be had in looking, and Nelson compels one to do so. Indeed, while his work has long been immersive—think of the disorientating paranoia of The Coral Reef (2000), which seemed to aggregate with each room—it is the detail to which Nelson draws one’s eye most skillfully. The machines—stilled—slow one also, and gather one’s gaze like lint upon spindles. Short lengths of silver thread have fallen in mute gestures upon a dusty ledge and one wonders what could be made of them; nearby metallic ribbons in reds and green, blue and gold, are placed hanging on bent wires in a dull cupboard, as enticing, as pathetic, as imploring, as votive offerings.

What would be hoped for? Hope, probably, as there is little to be found here. For not only does this exhibition represent the loss of British manufacturing, it also represents the loss of the state, or versions of it, or those institutions that might be thought to represent it. One enters through doors salvaged from an old London hospital, and corridors leading to the Tate’s other galleries are constructed from timber salvaged from Victorian barracks; four plaques commemorating the coronation of George VI and the Queen Consort, Elizabeth, in 1937—the year the Duveen Galleries were opened—proclaim “Long May They Reign,” although they didn’t reign for long, not really, and one is left to ponder the immense changes that were then about to come, and which are about to come now.

Inevitably the installation will be considered a portrait of a nation and of its people, and of particular people, too. It is hardly surprising that so many of the machines here are from textile factories when one knows that many of Nelson’s family worked in them. Three of the machines one encounters here were made in Leicester, a city just south of the artist’s Loughborough birthplace. And so one is drawn back to the spools of sequined ribbons and those women who in factories across the industrial Midlands would spend their week making the clothes they’d wear out at the weekend, this decorative trim that would mark the edge of that which was perhaps otherwise unremarkable. But no longer: upon one metal surface is scrawled in black marker “Reject Friday.”

This is a profound and affecting exhibition in which a bottle of dishwashing liquid seems to bear as much weight as a giant set of scales. If the elegy was traditionally defined in relation to the epic form, then here Mike Nelson has demonstrated his mastery of both.