The critical literature on the photographer Peter Hujar’s work remains relatively slight, and that of value slighter still. One explanation for this is the limited primary material available; Hujar was coterie-famous in his lifetime, but never garnered the exposure that would generate a significant body of contemporary criticism. For reasons in part attributable to his difficult childhood—his father left before he was born, his mother was an irascible and sometimes abusive drinker who left him with his Ukrainian immigrant grandparents for the first years of his life—Hujar refused paternalism of any kind, either toward himself or his work, and he maintained an ascetic, almost Beckettian attitude toward speaking on behalf of either. He wrote almost nothing about his photography for publication. Many of his letters are lost. On the single occasion he was invited to speak before an audience he failed to prepare and froze at the lectern.1 He granted very few interviews, and in those he did allow he is a bristling, sprung, nervous subject, evasive to the point of embarrassment. In the only extensive interview he gave, conducted by his sometime lover and protégé David Wojnarowicz, almost the first thing he says is that he will not discuss “why I do what I do.”2

One result of this refusal or inability to speak on behalf of his work is that the Peter Hujar we have is spoken in other people’s voices. He comes to us second-hand in interviews with friends and associates often conducted decades after his death from AIDS-related pneumonia on Thanksgiving Day 1987. Wojnarowicz, who also died from AIDS complications in 1992, recognized the danger of a posthumous reputation delivered by witness: “I have the attraction to document things because with Peter, I saw how little was documented of him after he died. I saw all the photographs he left and how little of himself there was.”3

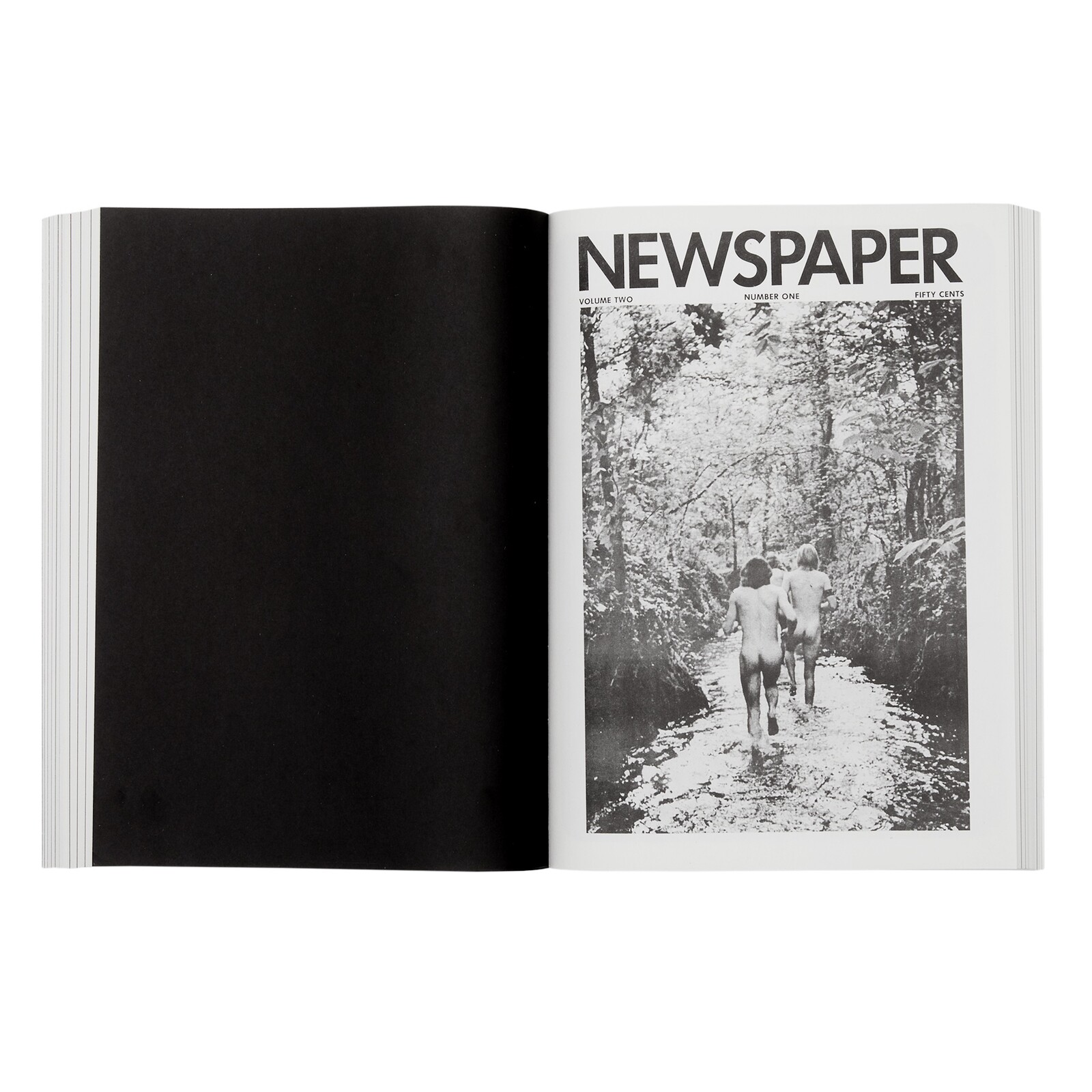

A point often insisted upon in these recollections is that Hujar had little interest in the institutionally recognized vanguard art of his time, namely Minimalism and Conceptualism. Wojnarowicz spoke to the untimeliness of Hujar’s work when, with Conceptual and post-Pictures generation photography in mind, he wrote that it “blows a hole through the artworld sanctioned view of photography in the later part of the twentieth century.”4 There are, though, materials emerging from the archive that provide opportunity for a nuancing of the critical narrative. The art historian Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez and the publisher Primary Information have done valuable work toward this end by collating and publishing every issue of Newspaper, a textless journal published by Stephen Lawrence and edited with Peter Hujar and Andrew Ullrick (a currently unidentified figure; Yáñez speculates that the name could be a pseudonym for Hujar himself) during the late 1960s and early 70s when Hujar and Lawrence were lovers sharing an apartment at 188 Second Avenue in the East Village, an apartment that also served as the journal’s offices registered, resonantly, as Affinity, Reality, Communication Inc.

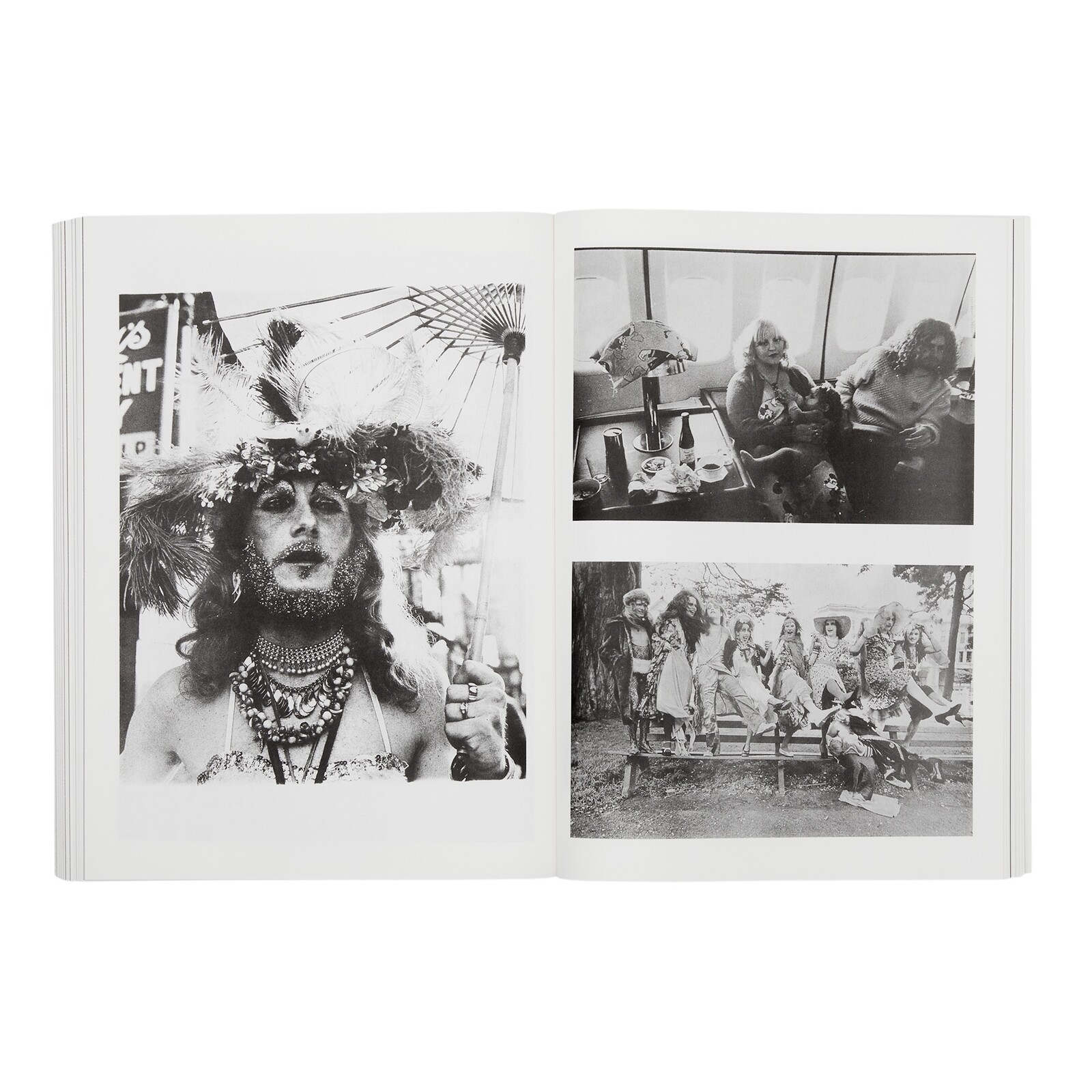

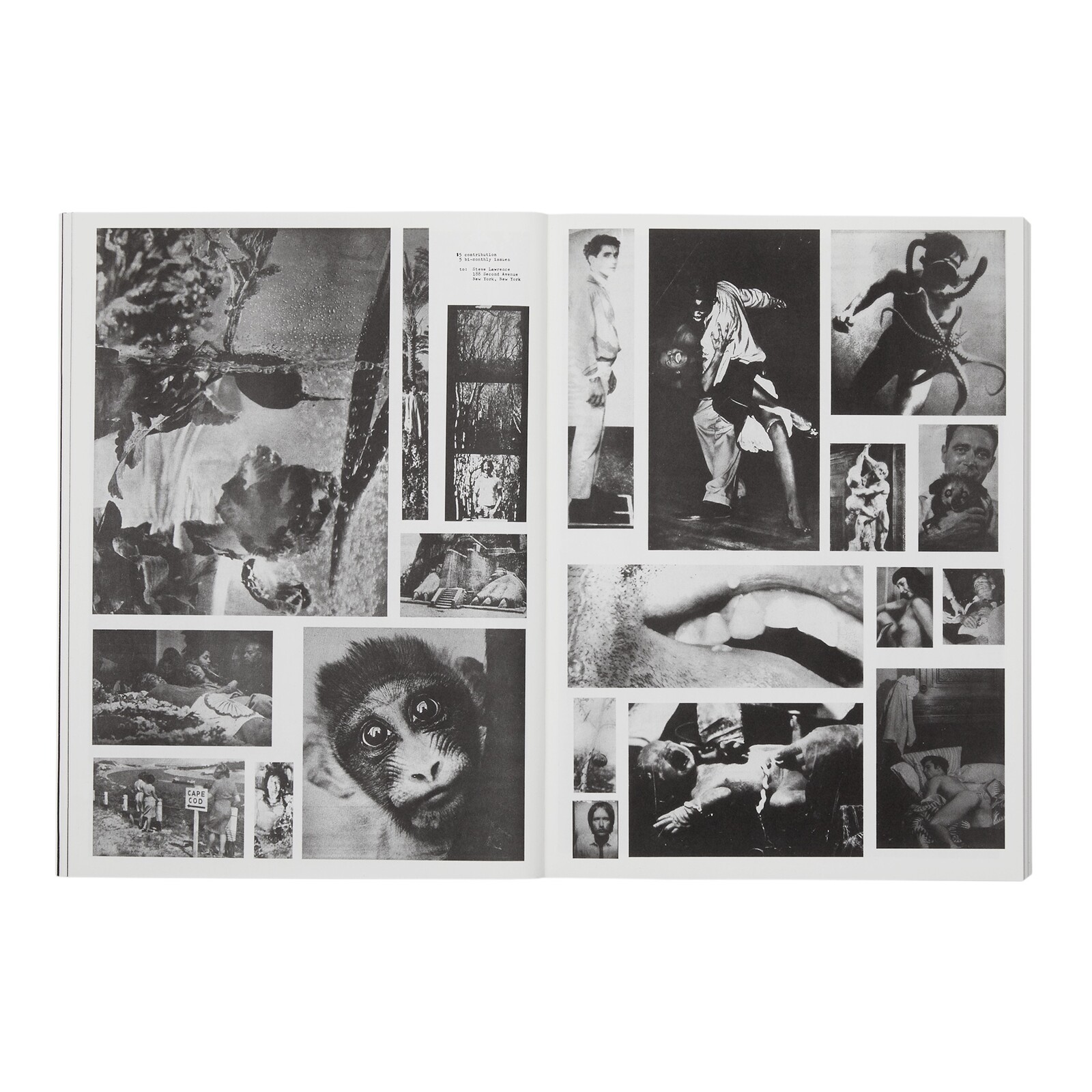

The journal looks like a conceptual object. Images from gay and straight porn, mainstream and countercultural news media, advertising (sometimes commissioned adverts, though they are placed within the journal without being obviously so), work by artists including—amongst many others—Paul Thek, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Ray Johnson, Andy Warhol, Yayoi Kusama, Peter Beard and, in every issue, several images by Hujar himself, are arranged within the foundational structures for Minimalism and Conceptualism, the series, and the grid. Yáñez has written that Newspaper “championed a method of chaotic reading of images.” “The apparent chief concern for Hujar and Lawrence in arranging the pages of the magazine,” he writes, “was that images were brought together from disparate contexts, mixed up, and placed together in a way that forced meaning and correspondence beyond their apparent lack of connection and/or hierarchical distinctions.”5 It’s a line that chimes with arch-conceptualist Sol LeWitt’s description of his “Serial Project No. 1” in Aspen 5-6 (1967) where he wrote that the aim of the serial artist “would not be to instruct the viewer but to give him [sic] information. Whether the viewer understands the information is incidental.”

Peter Osborne regularly invokes Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller” to elucidate the historical process whereby narrative gives way to information. In his Anywhere or Not At All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (2013) he writes that:

The historical meaning of the concept of information appears most clearly in Benjamin’s 1936 essay “The Storyteller,” which recounts the epochal historical transition from an oral narrative tradition, directed toward transmitting the “epic side of truth”—namely wisdom—via the rise of the book form of the novel, to the “new form of communication” of information. Information, associated with the newspaper, is understood to produce a crisis in the novel.

Osborne recognizes the historical sequence epic-novel-information as having been “replayed at high speed in the curatorial history of conceptual art between spring 1969 and autumn 1970”, exemplified in a swift run of exhibitions across the West.6 Newspaper was included in one of these shows: “Information,” held at MoMA in July 1970. In a sense this appears remarkable, given the narrative of Hujar’s apparent disinterest or disdain for Minimalism and Conceptualism. In each issue of Newspaper one of the unifying elements was the “environment,” a grid of images constructed by Lawrence, who created an expanded wall-based version of such an “environment” at MoMA. The piece was slightly different from the environments found in the print journal, since it focused more on media images than the pornographic or artistic materials that often accompanied these in Newspaper. Nonetheless, an image by Hujar was included; his work did appear in, as Osborne says, one of the “seminal” historical exhibitions of conceptual art alongside work by Vito Acconci, Mel Bochner, Lucy Lippard, Lawrence Weiner, and the rest.

It’s a fascinating historical anomaly, one that opens onto a resonant historical counterfactual: toward the end of his life Douglas Crimp, famous as the curator of “Pictures,” the 1977 show at Artists Space that is often seen to have inaugurated and canonized post-modern photographic practices, and an editor at October until a crisis prompted by what he saw as the journal’s failure to engage seriously with the culture and activism of the AIDS crisis, had wanted to curate an exhibition of Hujar’s work. Ultimately that wish was partially realized as the “Mixed Use, Manhattan” exhibition he curated with Lynne Cooke at the Reina Sofia in 2010, a more expansive exhibition of photographic and film-based work made in Manhattan from the 1970s up to the exhibition’s present. Hujar’s cityscape work appeared there in conversation with practices that were influenced by him, such as those of Wojnarowicz, Zoe Leonard, and Moyra Davey, and with others less commonly brought into his orbit. That is to say, the show made a case for reading fluidly across or beyond certain ideologically or generationally fixed divides within the discipline of art history in the service of a more historically and materially sophisticated model of the field. Nonetheless, that an exhibition curated by Crimp failed to materialize is a serious loss for Hujar’s reception. It remains the case that Hujar’s art is often erroneously over-associated with the East Village scene when that association is more anthropological than aesthetic.

Crimp begins his 2016 memoir Before Pictures by discussing the two rooms at Max’s Kansas City, the bar and nightclub at 213 Park Avenue South famous as an artist’s hangout in the 1960s and 70s. In the front room drank a largely male, imposingly hetero crowd of “serious” Minimalist and Conceptual artists—Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Sol Lewitt, and so on; in the back were the speedy, queer Warhol set.7 Like Crimp, Newspaper straddles those two rooms both figuratively and literally. Literally, because Lawrence sold copies of the journal there. Warhol is said to have been a fan, and there are photographs of Lawrence with Warhol at the Factory in which the latter is seen reading a copy. Indeed, during the 1960s both Hujar and Lawrence were in close orbit with Warhol, and his influence on Newspaper is pronounced. Joel Smith, who curated a major Hujar exhibition at the Morgan Library in New York in 2018, characterizes Newspaper as a “Warholian project”, one that celebrated “photography’s knack for getting into and taking over everything.”8

Figuratively, Newspaper crosses between those rooms because in its format it appears as a conceptual object. But if it is such then it queers, or “swishes,” to use Warhol’s word, what that kind of object might be. Like certain feminist practices that ironized elements of the conceptual lexicon (Carolee Schneeman’s Sexual Parameters Charts, for instance, where to serious comic effect women are asked to fill out a grid that charts the “sexual parameters” of sex with men—duration of encounter, genital size, use of words, volume of semen, etc), Lawrence and Hujar produce a comic queer configuration of conceptual art that speaks specifically to a gay art-world-adjacent coterie in downtown New York, to the high into low/low into high strategies of “camp.” The journal’s first titled issue has at its center a piece by the British artist Gerald Laing that presents a game in which the viewer is asked to match the portraits on the right-hand page with the penises printed in ink on the left. The portraits are all characters from the queer art scene of the time, and the piece invokes a kind of salon joke that separates those inside from those outside. Indeed, the journal muddies every category it engages: advertising is inseparable from non-commercial images, art from porn, war photographs from images of domestic life, and all in a format that can be found bogged in the gutter or raised onto the pure white walls of MoMA.

There are no copies of Newspaper in Hujar’s personal archive, and the question is open as to what importance he attached to it later in life. But elements of its formal strategies can be traced through the more significant photographic work of the 70s and 80s, for instance in the photograph West Side Parking Lots, NYC taken on the Lower West Side in 1976. The car park is, of course, a formal grid, as are the forms of the commercial buildings that surround it, but as with so many of Hujar’s images of the gridded totems of midtown Manhattan or the Financial District, the image is composed in a series of diagonals that cut across the squares of the formation, that break the formal solidity of the box. There is also a queer joke embedded in this picture: the words “park here” printed on the building top-left, and below them the word “leather.” These parking lots were a cruising ground for gay men in the 1970s, and they were near the infamous leather club The Mineshaft, which was located at 835 Washington Street.

It’s another in-joke for the queer demi-monde audience Hujar associated with and photographed, and I don’t think it’s pushing it to locate a critique of Minimalism here, whether it was entirely consciously made or not. After all, another of Hujar’s (and Susan Sontag’s) lovers through the ‘60s had been Paul Thek, with whom he shared several formative experiences that fed into both of their artmaking, not least the trip to the Palermo catacombs where Hujar captured his famous photographs of the dried-out and theatrically arranged bodies that would make up the second part of his monograph Portraits in Life and Death (1976). Thek’s work is often read as a critique of minimalist tenets, particularly his vitrine works, where the polished object of minimalist sculpture was replaced with representations of striated meat and human body parts.

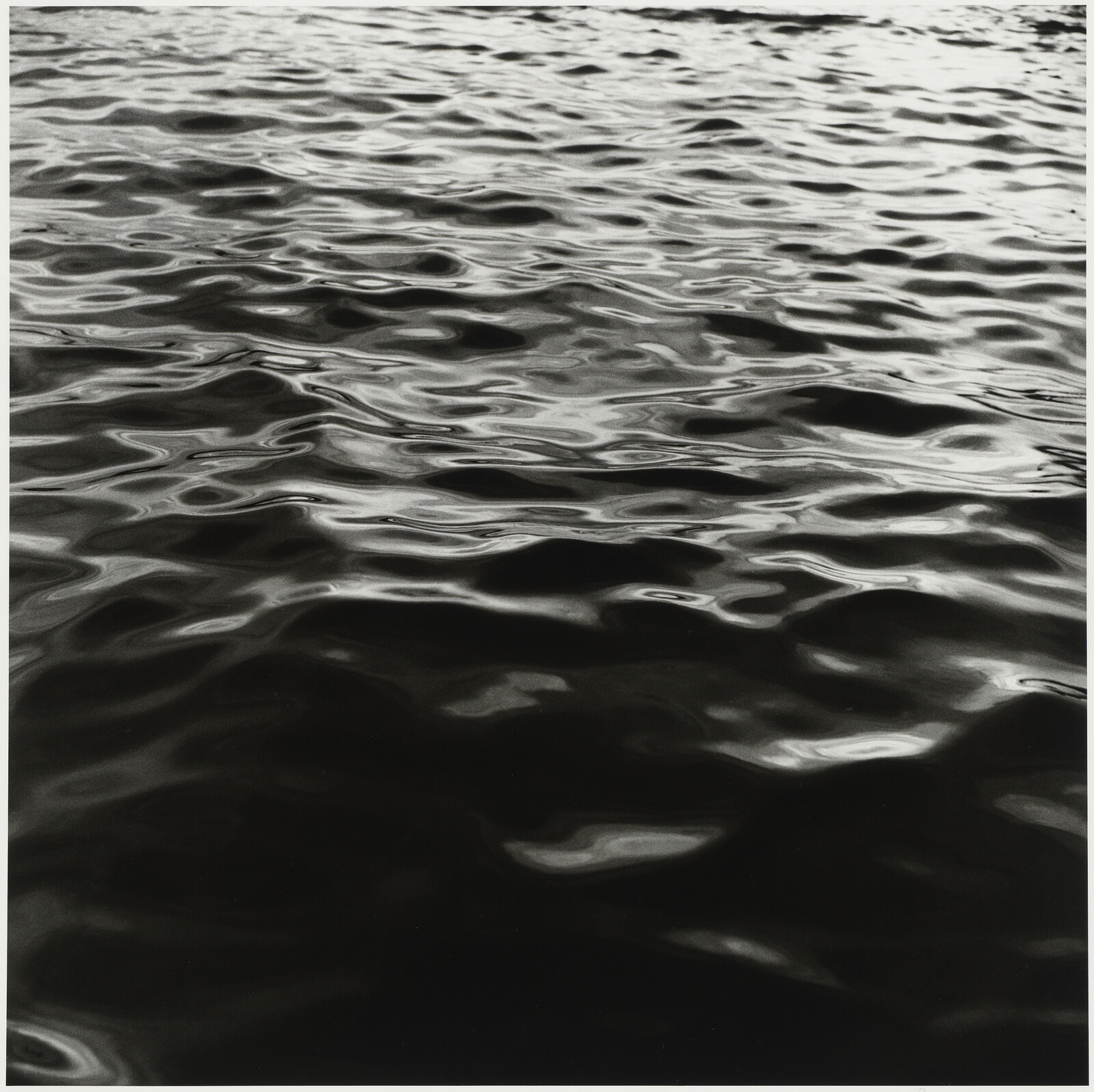

The grid and the series appear once more, in the final exhibition of Hujar’s life, held at Gracie Mansion on January 2, 1986, almost exactly a year before he received his diagnosis of AIDS. Hujar organized his images in a two-tiered band around the gallery walls in such a way that no genre of image would sit next to another of the same, either side by side or above and below: no landscape next to a landscape, portrait next to a portrait (human or animal), and so on. The result once more seems to engage the legacy of Minimalism with implied critique, but here that critique has been assimilated to a deeper purpose. The series ends with two portraits one above the other, suggesting that yes, the series, like life, does end. Yáñez describes the construction as one that produces “fluid associations” between particulars, a movement in time back and forth and up and down, an anarchic set of relations, a meditation on liquidity across all its various meanings, the glittering of visual consciousness and a complex model of relationality.

There is, then, a dialectic between liquidity and construction at work in Hujar’s later photography, one that begins to find expression in his work with Lawrence on Newspaper. It ends, for me, with a final image: Hujar’s eye to the gridded viewfinder of his Rollieflex camera searches the surface of the Hudson River. He is standing by the piers somewhere south of 14th Street on the Lower West Side, an area that was then a site of radical artistic and queer activity at the frayed edge of Manhattan’s pragmatic grids. It’s an area that is now one of the most gentrified parts of any city in what McKenzie Wark calls the “overdeveloped world”, each brick saturated with liquidity, money pouring in from Silicon Valley, Saudi investment funds, the media and weapons industries, all forms of material—mineral, fossil, human— has been liquefied and then re-solidified, congealed there as real estate. Under these conditions the river becomes an image for the possibility of a different city. Writing of Mario von Bucovich’s image of the surface of the Seine that ends Bucovich and Germaine Krull’s book Paris of 1928, Walter Benjamin wrote: “Paris ends with an image of the Seine. It is the vast and ever watchful mirror of Paris. Day in, day out, it throws its solid buildings and cloudy dreams into this river as images. The river accepts this oblation graciously and, as a sign of its favor, breaks them into a thousand pieces.”9 The Manhattan shattered and spangled in the waters of Hujar’s images asks to be reconfigured in a radical new form, one true to its betrayed histories and the city’s sentimentalized, unwillingly martyred, or forgotten and unreconciled dead.

The anthology of fourteen issues of Newspaper was published by Primary Information in March 2023.

He had been invited to speak at the Port Washington Library. See: Cynthia Carr, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 186

Excerpts from the interview between Wojnarowicz and Hujar are available as part of The David Wojnarowicz Oral History Project here: https://wojfound.org/oral_history/peter-hujar/

Amy Scholder (ed.) In The Shadow of the American Dream: The Diaries of David Wojnarowicz (New York: Grove Press, 1999)

See: Julie Ault, “Notes Towards a Frame of Reference” in David Breslin and David Kiehl (eds), David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), 90.

See: /jeudepaume.org/en/mediateque/peter-hujar-and-the-brief-history-of-newspaper-by-marcelo-gabriel-yanez/

Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not At All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London and New York: Verso, 2013), 62-3

See: Douglas Crimp, Before Pictures (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 14.

See: Joel Smith, “A Gorgeous Mental Discretion” in Peter Hujar: Speed of Life (New York: Aperture, 2018), 23. The full extent of Hujar’s engagement with Warhol’s work is clarified in a document from March 1987. Just weeks after Warhol’s death, Interview magazine asked various art-world figures for their memorial thoughts, Hujar among them. He dictated his contribution to Stephen Koch, who copied it down and then edited it for publication. The unedited transcript, which Koch kindly shared with the author, is a fascinating fragment that records the way in which Warhol became, for Hujar, both a lodestar and a generative negative example. By March 1987 Hujar knew that his own AIDS diagnosis was almost certainly terminal, and he speaks movingly and tellingly of what he perceives to be a lack of respect shown toward Warhol in death. Warhol was, he says, “a man who made incredible changes in the artworld and in the concept of art.” He goes on: “God, it would have been so easy to be Andy Warhol. Sometimes I think it would have been. It’s like I had a sense of how to do it, but I wouldn’t let go, let go of my own little notions of the things I had to do… My work would have been different But I think I obviously wasn’t ready to do that kind of big letting go… It’s as if I’m living out something that’s essentially very Victorian… I compose the picture in the camera, it has my control, my image, I make the print, it has to be beautiful.”

See: Walter Benjamin, “Paris, The City in the Mirror: Declarations of Love by Poets and Artists to the Capital of the World” (1929) in Esther Leslie (ed) Walter Benjamin: On Photography (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 136-137