Ask Cincinnati native Tony Tasset for a sculpture and you’ll get anything from a giant eyeball to a depressed Paul Bunyan to a steel-and-resin rainbow. Invited to the inaugural FRONT International Triennial in Cleveland, Ohio, he made Judy’s Hand Pavilion (2018), a mammoth silver-colored fiberglass hand modeled on that of the artist’s wife, severed at the wrist, resting on its fingertips. It’s macabre and wacky, it provides some shade, and it’s a perfect selfie op—everything you could ask of a public work. On the other “hand,” it’s hard to shake the impression that, like some god-large developer, Judy’s Hand is reaching down to grab itself a piece of Cleveland.

FRONT is a new triennial that aims to bring the world’s crowds to Cleveland. Its many off-site locations pull the completist to remote corners of the host city, as well as nearby Akron and Oberlin, and thus FRONT courts (or can’t avoid) some degree of urbanism, since between each venue, inevitably, is the rest of the city. The filmy hopes of real estate speculators patinate Cleveland the way soot once did. One participating venue, Transformer Station Contemporary Art Space, so named because it used to be one, is now helping to “transform” the surrounding neighborhood of Hingetown (aka Ohio City). It’s a pun, but not an ironic one. FRONT offers evidence both for urban renewal and against gentrification at the very same time. It is not, however, a triennial about urbanism, and its artists are not shock troops. Instead FRONT proffers the idea that artists possess unique powers of perception, and can see a new city in an old one—can moonlight as entertainers, urbanists, tour guides, and realtors—whether they’ve spent much time there or not.

FRONT artists were apparently asked for site-specific projects. This does distinguish the show from the dozens of other internationals, yet this application of site-specificity is often toothless, resulting more in Cleveland-flavored, Cleveland-themed pieces than in challenging, interesting art. For instance, a social practice–style sausage by John Riepenhoff called Cleveland Curry Kojiwurst (2018) employs a multi-ethnic “spice profile” to make Cleveland’s stereotypical staple convey the city’s variety. Similarly, Marlon de Azambuja sculpts an ant-scale city center using building materials common in Cleveland, a sort of urban portrait in terracotta pipes and marble blocks. Perhaps someone will be impressed by the artist’s observation that Cleveland has a lot of pavers. Similarly, The Dispossessed (2018) by A.K. Burns comprises two contorted sections of chain-link fencing, painted with flashy purple automotive paint and set into the Transformer Station’s lawn. The piece echoes the fences in nearby front yards and vacant lots, an ad-hoc response to (and, sometimes, sign of) blight. Burns gives this vernacular form an almost sarcastic candy coating and crumples it just enough to suggest that the piece might also be critical of this style of working, and of the smooth narratives of boosterish biennials in general. Even so, it’s a gentle nibble on the hand that feeds the artist—and still mildly patronizing: no one needs an artist to point out that Cleveland, like many other places, has chain-link fences.

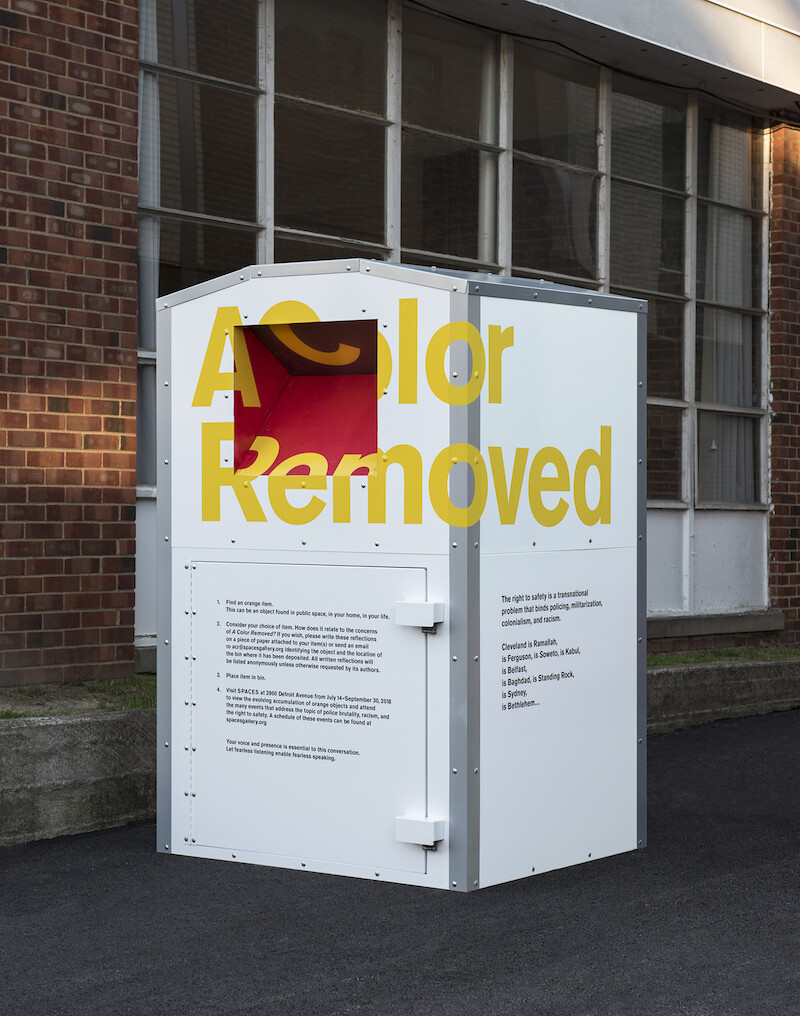

Allen Ruppersberg, however—perhaps because he’s Cleveland’s native son—contributes a sensitive work, “Then and Now” (2018): a series of large-scale photographs of different Cleveland views inset into mural prints of the billboards that now block them. The result is a playful ghosting, above nostalgia; for all appearances, the artist’s vision penetrates the city’s eyesores. Michael Rakowitz also takes a headier approach to Cleveland with A Color Removed (2018). The project isolates the local pressure point of a national disease—the police shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice as he played with a toy handgun that lacked the orange cap marking it as safe. Donation bins that Rakowitz placed around the city collect caution orange objects, referencing the missing piece of Rice’s “weapon,” and objects are continuously bricolaged in an orange-only installation that doesn’t feel vampiric, but rather draws on the community’s energy in a widely legible way and returns the work with interest.

It’s telling that three of the triennial’s most dynamic works enjoy the most “site-specific” placements, yet don’t mention Cleveland at all. Allan Sekula’s Lottery of the Sea (2006), a maritime labor documentary set mostly in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, screens in the historic cargo hold of the retired Great Lakes steamship William G. Mather; Dawoud Bey’s installation of rich, near-black day-for-night landscapes made along the last leg of the Underground Railroad in Ohio hang in a church that served as a waystation. Then there’s THE RENDERING (H X W X D =) (2018), Barbara Bloom’s deft investigation of the collection of Oberlin College’s Allen Memorial Art Museum, where she physically constructs the illusionistic space from a handful of paintings. There’s enough room between these projects and the histories of the sites themselves that the work actually deepens visitors’ sense of place, and of Cleveland, Ohio, USA, even as it extends beyond it. FRONT’s first edition is titled, archetypally, “An American City,” and in this respect one of the strongest exhibitions is down the highway at the Akron Art Museum; there, a group show brings together Vladimir Bonačić’s computerized grids of blinking lights with the minimalist urbanism of Jessica Vaughn’s grid of used bus seats; Myriam Jafri’s acerbic displays Product Recall: An Index of Innovation (2015) with some dozen paintings and reliefs by Nicholas Buffon depicting LGBTQ landmarks from Stonewall to Zoe Leonard on the Highline (2018). The work here isn’t about Akron any more than it’s about anything else, yet the pieces push and pull on the issues at the heart of northeast Ohio, from robot automation to Motown radio to civil rights.

But what about the locals? Building on two years of studio visits, artist and FRONT head curator Michelle Grabner has organized the “Great Lakes Research” exhibition, a grab bag of work by 21 artists from the region. The show is sequestered in the gallery and hallway of the Cleveland Institute of Art, a block away from other FRONT attractions (including Tasset’s pavilion) at MOCA Cleveland. On the one hand, this concentration gives a (global?) platform to local artists who wouldn’t necessarily have it otherwise, while, on the other, relegating even the best artists here to second status. In some circles, after all, “regional” is pejorative, implying a lower standard. To square this separation with the triennial’s regionalist bent is a sticky bit of diplomacy: to not at least nod to local artists would have been snobby. As for Cleveland’s storied working class, they too receive an abstract treatment. The Transformer Station presents Human Right (2016–17) by Stephen Willats, a combination of videos and placards that illustrate his research into a post-industrial town in England, the sort of self-made community that already holds places like Hingetown together, whether or not an artist notices. It’s a sharp piece, and an aloof one. On the wall behind it are 16mm films of graffiti, house numbers, chipping paint—anything, in short, that signifies anything.

These things also signify, if vaguely: fencing, concrete, sausage. Whatever connections this first batch of visiting artists claim to discover seem fairly superficial, if not obvious. As a tourism initiative, FRONT’s palatable idea of local flavor may well succeed in burnishing Cleveland’s rustbelt charms. But if FRONT means to offer insight into Cleveland’s secret life, or urbanism writ large, it will need to look harder. I can only speak for myself when I say I went to Cleveland hoping to see a new city as intimately as possible. I got that, but not from FRONT. On Cleveland’s light rail between the airport and downtown I overheard an animated discourse between total strangers that ranged from sentencing guidelines for heroin possession and how drug preferences track with race, to lamenting basketball star LeBron James’s recent forsaking of the Cleveland Cavaliers for the L.A. Lakers. Give me an artwork that comes anywhere close to that.