Cosey Fanni Tutti’s exhibition at Cabinet Gallery is divided into two parts, a photographic exhibition and a film, which together invite the visitor to negotiate not only questions of morality but also archival memento mori. Upon entering the upper gallery, the viewer confronts frames from Cosey’s 1977 photographic collaborations with the American photographer Joseph Szabo, selected from his archive by the artist and retitled Szabo Sessions (2017). Their collaboration plays upon the blurred boundaries between commerce and art, which the artist has confronted through the interposition of her own body in the course of a career stretching back almost half a century.

Szabo’s photographs raise again the uncomfortable questions that Cosey has posed about women artists’ agency to perform and spectacularize their own bodies and their own desire, particularly when that agency touches upon female power as a form of monetary exchange. But Cosey exceeds the neat lineage which a feminist discourse might trace from Hanne Wilke’s S.O.S Starification Object Series photographs (1974-82) or Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll (1975) to the riot grrrl abandonments of Pipilotti Rist or Tracey Emin’s confessional video Why I Never Became A Dancer (1995). Those works signal a critical deployment of the body within the context of art, addressing their audience with anger, entreaty, even shame. By contrast, Cosey crosses over into pornography. In Szabo’s glossy photographs she looks into his camera with a stark and insolent gaze. Yes, her directness could be read as a feminist recalibration of the peekaboo provocations of conventional glamor photography, but there is also the suggestion that she is doing this for pleasure, not under sufferance.

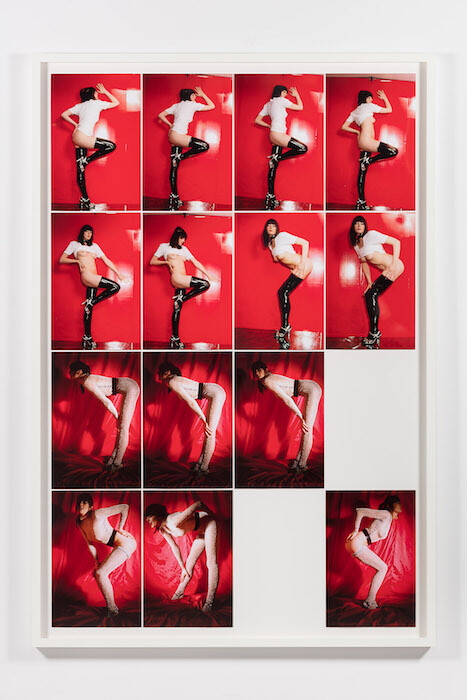

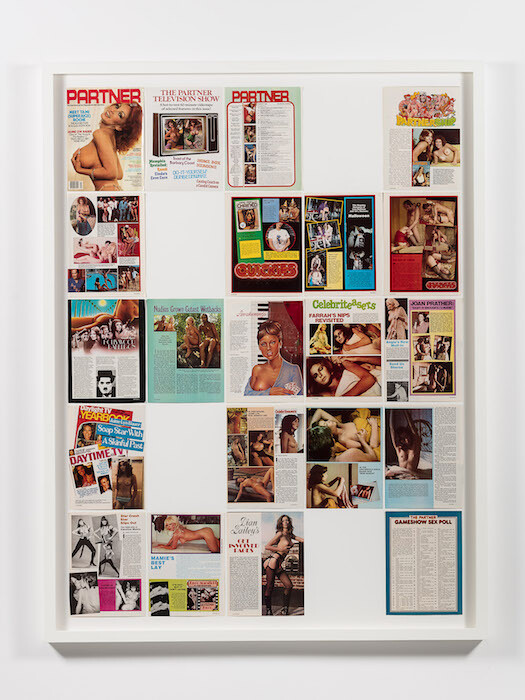

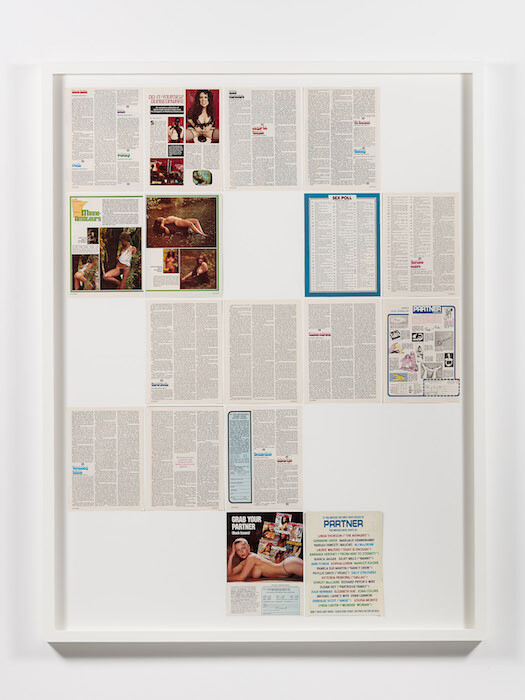

Consisting of contact sheet blow-ups rather than single images, and advancing click by shutter click, Szabo depicts Cosey in the shiny PVC costumes and sexually provocative poses of sadomasochistic pornography. The successive frames are a reminder of Szabo’s working process, as Cosey’s adept performance of sexual display unfolds for the camera, recording her sinuous turns, full frontal, and back. The photographs were originally intended for commercial sale to pornographic publications and, across the gallery space, adjacent walls display a framed collage of the full issue of the glamor magazine Partner in which Szabo’s images featured (“Throbbing Gristle,” Partner, Vol. 1, No. 9, February 1980, 1980). Thus far the display delineates the journey of the image from shutter release to glossy page, and the migration of private female sexuality into the voyeuristic public gaze. But the story is complicated by the nature of Cosey’s representation in the magazine: not as pornographic model but as musician.

Szabo’s explicit images accompany a written feature on Cosey’s role as a member of the band Throbbing Gristle, with the stress on her sexually liberated attitudes as artist and musician rather than her titillating appeal to the male reader. The article’s opening sentence provides more insight than it perhaps realizes into the complex persona that Cosey presents: “Cosey F. Tutti, topless dancer, street player, recording artist, gets her kicks horrifying the Cholesterol Generation.” The list of labels signals how Cosey traverses cultural and economic taboos, and provocations, beyond the circulation of her body within the pornographic economy: from Throbbing Gristle’s industrial noise to the performance art confrontations for which she has been known since the 1970s. But even if Cosey’s images in Partner function as a subcultural intervention rather than a wholesale engagement in the pornographic industry, her presence on its pages succeeds in flattening the hierarchies between cultural and pornographic representation, as she draws to our attention how all are at equal play in the proliferation and circulation of the commodified image. This familiar, but still unsettling, argument gathers a further facet and force as the works hang for sale on Cabinet’s white-walls.

Could Cosey’s interest in penetrating these different spaces be seen as a form of political or feminist activism, enacted by going undercover in the sex industry? Or a pleasure-seeking curiosity to penetrate what morality has rendered taboo—as sexual performance, as music, as art? Her recent autobiography (Art Sex Music, 2017) offers candid insights into how she perceives no boundaries between her lived experience and artistic practice. Unaware of this, the visitor might experience in Cosey’s work not so much a merging of life and art as a reminder of the sharp lines of morality separating what constitutes pornography from culture’s accepted images. If her work urges dialogue across this line, it makes it no easier to navigate, as we move from the stark elegance of Szabo’s full frontal photographs to the centerfolds of Partner and, finally, to her recent film, screening in the basement.

Harmonic COUMaction (2017) offers autobiographic disclosure as photographic slide show, beginning with black-and-white scenes of the artist’s childhood which morph and melt into later incarnations with band members and friends, blank images of unpeopled streets and buildings and, finally, street performances. This personal archive holds out the promise of a glimpse behind the more constructed images of musician, artist, or pornographic model represented upstairs. But the features in the photographs dissolve into uncanny obfuscations before it is possible to reflect upon their backstories. Indeed, the film’s unsettling digital transformations only draw attention to the voyeurism inherent to our invasion of the artist’s private realm: as if the viewer’s gaze is responsible for their facial disintegrations.

Yet the photograph is itself subject to the manipulations of time passing, and the frozen dynamics of Szabo’s photographs now represent a memorial to their collaboration at the same time that they rehearse its sexual politics. The exhibition suggests that it is through performative dialogues such as these, mediated by the camera, that Cosey has been able to traverse territories often placed out-of-bounds for the woman artist. In this exhibition, by reprinting Szabo’s photographs and in the snapshot superimpositions of her film, Cosey appears to honor and acknowledge those collaborators, in art and music, who have helped her to explore different aspects of a multifaceted life: one whose own ambivalence concerning these differently demarcated images of sexuality invites us to confront our own.