Is that hysterical laughter? And are those accelerated heartbeats the phantasmagoric echoes of Chile, circa 1973? These sounds are not leaking into the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes but are rather the reverberations of an album released that same year: Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, which plays on a loop in this exhibition of works made by Alfredo Jaar between 1974 and ’81. Jaar was seventeen when General Pinochet’s coup d’état tore his country apart, and the young artist sought refuge in this soundtrack of madness and despair.

Pink Floyd’s front-man and lyricist Roger Waters last year released The Dark Side of the Moon Redux, a “reimagining” of the album from which this retrospective takes its title. Where he chose to replace David Gilmour’s guitar solos with homiletic spoken word, curator Pablo Chiuminatto has gone the other way. Rather than over-explain, Chiuminatto’s approach offers little contextualization or research for Jaar’s early works, which mark a turning point in the career of one of Latin America’s most significant artists.

The restrained curation lends the show a provisional feel, an analysis of sketches by an obsessive apprentice. These range from Jaar’s initial experiments with dry-transfer lettering methods, such as 11 de Septiembre, 1973 (1974)—in which every day on the calendar after the “other” September 11, the day of Pinochet’s US-backed coup, is also numbered 11, in a nightmare version of Groundhog Day (1993)—to the simple gesture of isolating photographs included in Henry Kissinger’s autobiography, identifying the former US Secretary of State with a red circle in Buscando a K (1984). Kissinger’s role in the Chilean overthrow is protested by the indignant Jaar, who dedicated several works to the recently deceased 1973 Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Among those included here is a small fish tank inside which a doll-like Kissinger is presented bound, like an effigy (What Happens in the South is of No Importance (Henry Kissinger), 1984).

If aspects of “El Lado Oscuro de la Luna” feel tricksy, it’s worth noting that Jaar was a magician in his spare time. A self-portrait of the artist dressed with a top hat, bow tie, and wand is included in the exhibition, not only to publicize his Sunday hobby, but also to allegorize the artist as a maker of illusions—one who offers escape from an overwhelming political reality. This survey of Jaar’s beginnings, particularly shown alongside archival and ephemeral works including a scaled-up version of a letter he wrote to a company when he had the idea of importing juicers to Chile, raises questions about the merits of dedicating an exhibition to works that often feel like exercises pulled from a sketchbook; an uneven record of trial and error.

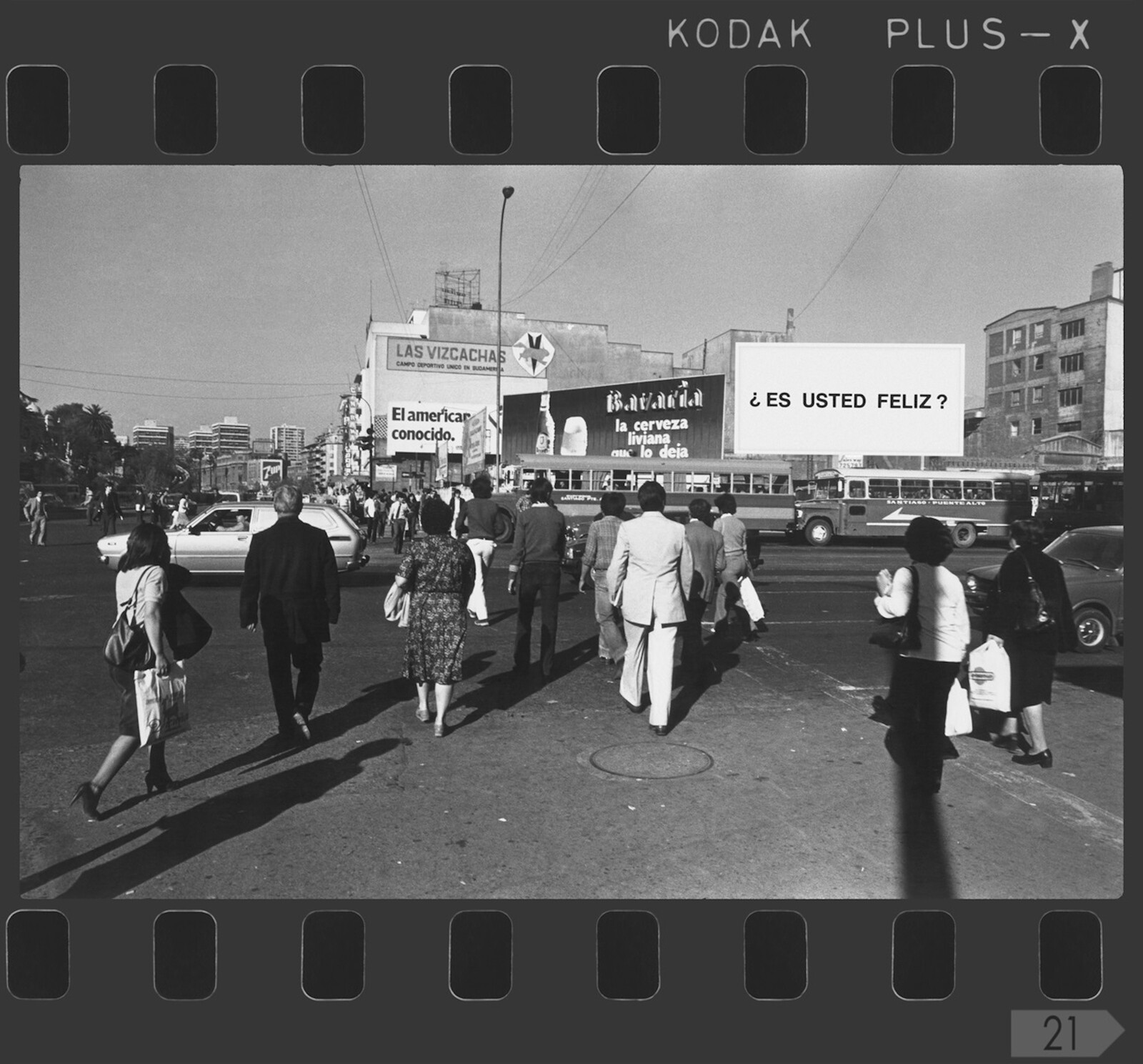

It does, on the other hand, offer a valuable opportunity to trace the establishment of Jaar’s modus operandi; namely, the appropriation of the aesthetics and modes of mass media to generate works that are not polysemantic, but rather focused on communicating a single message.1

In 1982, Jaar left Chile, tired of a murderous military regime that did not allow freedom of expression. In the final work made in his motherland, “Chile 1981, antes de partir,” a series of photographs documenting a performance made in its titular year, he divided the country from the mountain range to the sea with a strip of a thousand Chilean flags, raised like witnesses to the polarization of a population then split between support and rejection of the dictatorship.2 Soon thereafter, the artist settled in New York, where he had access to images that were prevented from reaching the Chilean public by censorship. The result of this discovery is the most relevant work in the survey, since it’s his first bid of an operation that will become a constant in his time to come. In Rostros (1982), he focuses on five photographs of events that occurred during the Pinochet dictatorship that were published in foreign magazines. Jaar points to faces that go unnoticed but which, once isolated and enlarged, reveal indelible expressions of pain, fear, and suffering. In doing so, the work demonstrates that enlarging gestures and expressions of horror can synthesize the feeling of an entire nation under threat.3

This marks a powerful shift towards the vindication of the image, which Jaar later consolidated in works not included here but now inscribed in the history of art. Among these are May 1, 2011 (2011), Lament of the Images (2002) and The Rwanda Project (1994–2010): in each, the artist inserts himself into a lineage of creators who assume that the best way to understand a collective trauma is through individual emotions and expressions.

In a conversation organized for the exhibition between the curator, Pablo Chiuminatto, and the artist, Jaar reaffirmed his commitment to works of art that communicate single ideas. According to Jaar, this is due to the Cartesian education he received in which good communication was mandatory: “Encuentro entre el artista y el curador. Alfredo Jaar: El lado oscuro de la Luna,” Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (September 20, 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1pMhsgfbUdM.

This polarization continues today, as demonstrated by Chile’s recent attempt to write a new constitution (the current one was ratified during the dictatorship) which was rejected in a close referendum.

This is the same tactic used by other artists, like the filmmaker Costa-Gavras. In Missing (1982), he illustrates the horror of the Pinochet dictatorship not by showing torture or executions, but the desperation of the wife and father of a missing person. See John J. Michalczyk and Susan A. Michalczyk, Costa-Gavras: Encounters with History (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022).