The Egyptian artist Hamed Abdalla painted mothers and farmers and letters and landscapes but the subjects he returned to most often, in each of the many disparate phases of his career, were lovers. This jewel box-sized exhibition devoted to Abdalla’s work, organized by Morad Montazami and Madeleine de Colnet of the Paris-based publishing and curatorial project Zamân, features six of his amorous pairings. The earliest lovers in the show are Les Amants de Shemm Ennessim [The Lovers of Shemm Ennessim], from 1953, a sweet gouache on silk paper showing a couple in traditional dress, facing each other demurely in profile but slyly extending their arms to embrace. The figures appear stylized and flattened, and clearly, Abdalla was inspired by a celebrated genre of hand-painting on glass depicting Antar and Abla. Those two are the hero and heroine of pre-Islamic poetry (composed by Antar himself, full name Antarah Ibn Shaddad) relating the episodic adventures of a black warrior poet who was born a slave but became a knight and the smart, beautiful woman who defied her family to be with him.

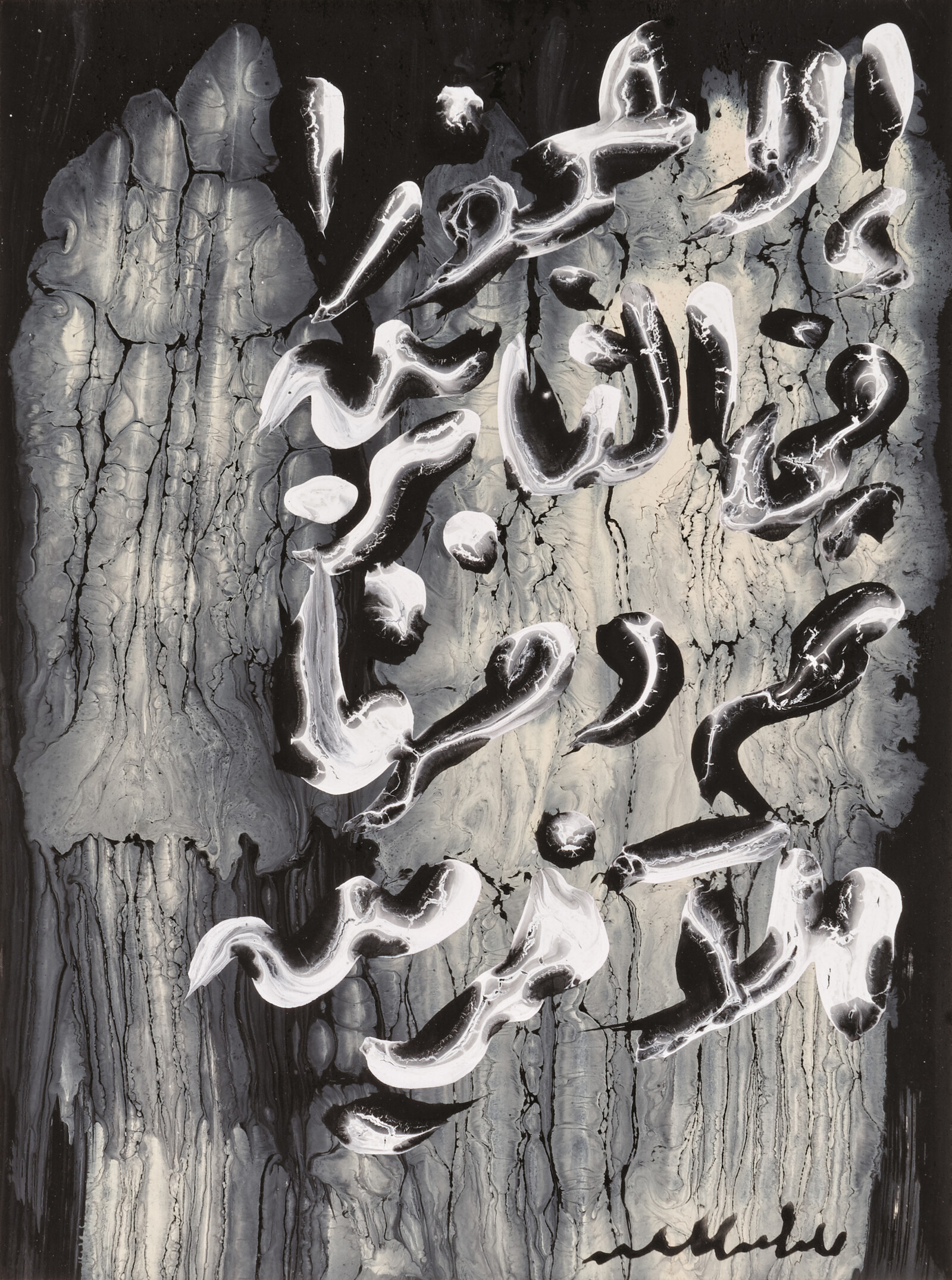

The last of Abdalla’s lovers, in a show conceived as part of a series and wedged into the museum’s permanent display of Paul Klee’s work, are the more diminutive Lovers of 1982. Here, thick letters in white spray paint on black paper spell out the word al-hob (“love” with a definite article in Arabic) while morphing into two human figures, one bending sharply from the middle to suggest their sexual union. In between are portraits of peasant couples, near total abstractions, and several works, including the explicitly phallic Al Hannaq [Tenderness], from 1958, and Désir, made with a blow torch in 1963, which delve into the dramas of love, sex, and other binary intimacies.

Abdalla was born and raised in Cairo. The son of farmers, he earned a degree not from the School of Fine Arts but rather from the School of Decorative Crafts. He wasn’t so much self-taught as he was stubbornly committed to intense periods of exhaustive self-study. On his own he contemplated folk art, geometric patterning, and Pharaonic reliefs, each palpable in early paintings such as the faux-naif Asfour (1955). Abdalla spent six months in Luxor and Aswan studying vernacular Nubian art and ancient archeological sites. Over a lifetime he constructed an extensive archive of source materials, including books, newspaper clippings, postcards, and, fortuitously, a glass painting of Antar and Abla. In what Montazami describes as his self-styled “community of minds,” Abdalla grappled with European modernists such Wassily Kandinsky and Klee, whom he considered his equals, and given the transformations Kandinsky and Klee had each undergone in North Africa, drawing from the same civilizational wells as he was.1 Abdalla’s first solo show in Cairo coincided with the inaugural exhibition of the Egyptian surrealist group Art and Liberty. While Art and Liberty agitated against the horrors of fascism in Europe, Abdalla addressed the internal tumult of Egyptian, Arab, and Muslim societies, torn between revolution and repression at the time.

When Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power, in 1954, and began enlisting artists to glorify the Egyptian peasantry and the working class, Abdalla saw the coming disenchantment. In 1956, he left the country seemingly for good. He spent ten years in Copenhagen, where he was close to CoBrA, and eventually settled in Paris. Far from home, Abdalla ripped through groundbreaking experiments with writing, calligraphy, letter forms, and the malleability of language. One can track the results specifically by following the artist’s Lovers of 1957 (an angular, figurative watercolor), 1960 (graffiti-esque bubble letters in plaster and linoleum glue on wood), and 1975 (bold, gestural forms evoking script), as well as by moving from the cursive tail- and bowl-like patterns on the dresses of his Mères des Martyrs [Mothers of Martyrs] (1956), to the flesh-toned bodies that seem to sit and stand on a beach below sea and sky while spelling out the titular Allah Akbar (1968).

“Hamed Abdalla” is part of a patently ambitious effort to rewrite art history to allow for the experiences of exile and, in so doing, to break the containers of national narrative, which are too narrow and too limited to accommodate an artist as fascinating and canon-busting as Abdalla. The show also follows a bigger retrospective of Abdalla’s work held in 2018 at the Mosaic Rooms in London, replete with a hefty catalogue. But even reduced to one large room and some fifty paintings, this show loses nothing from that one in terms of scope. It covers all of Abdalla’s critical periods, from a delicate Aswan drawing, 1946, to the talismanic powerhouses of the 1970s and the monumental series “Gens des cavernes “ [People of the Caves] (1975–76), named for a story in the Qur’an.

Moreover, the exhibition’s concentrated size helps to crystallize the questions Abdalla’s oeuvre provokes. How does his work with letter forms compare to that of the Sudanese artist Ibrahim al-Salahi, who imagined breaking lines of calligraphy until figures and spirits appeared? What would it mean to read Abdalla’s evocations of poetry, not least the riotous and bombastic Poem (1970), alongside those of the Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair, who conceived of verses as modular and variable sculptures? Is the notion of hurufiyya (from the word for “letters” in Arabic) still useful as the name of a movement, pioneered by the Iraqi artist Madiha Umar, among others, or a general category of cultural production? Could it be reconfigured into a more challenging theory or combustible analytic? And what is the deal with all those lovers, and the significance of gender and sexuality in Abdalla’s work more broadly?

“Hamed Abdalla” doesn’t answer any of these questions. It does, however, flip the usual script of a western museum wading into the regions of the world it once colonized, only to end up valorizing the ways in which its own artists mopped up influences there and refined them into Modernism, as if there were never any other artists to be found. Making space in a museum like this for serious, monographic exhibitions of artists such as Hamed Abdalla (and Etel Adnan at the same institution six years ago) is therefore a promising sign of what could become a more generative system of reciprocity.

Clare Davies, Kristine Khouri, and Ezzedine Naguib, Hamed Abdella: Arabecedaire, ed. Morad Montazami (Paris: Zamân Books, 2018), 36–37.