Ken Lum is a prolific writer as well as a conceptual artist, deeply attuned to semiotics across media, whose past work includes a series of “language paintings” that depict nonsensical words in colorful designs. He would probably be amused to hear that I turned to the Oxford English Dictionary while trying to reconcile the seemingly divergent bodies of work currently on display at the Wattis Institute.

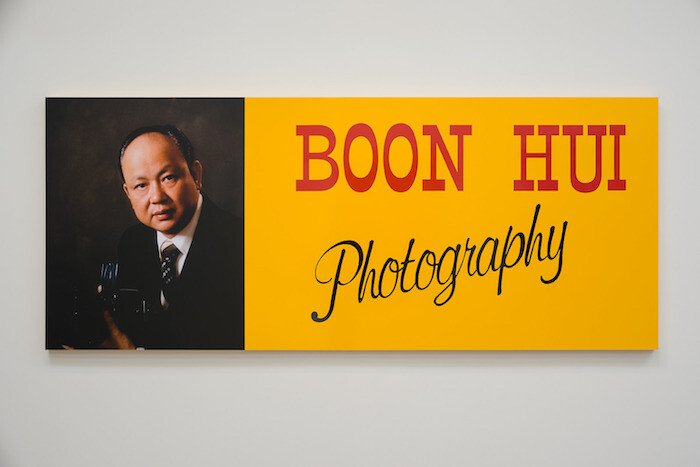

The exhibition “What’s old is old for a dog” (as far as I can tell, an invented idiom very much in keeping with Lum’s other fictional deployments of signifiers) is divided in two by a temporary wall in the middle of the main gallery. Each space contains formally and thematically distinct sets of works separated by over a decade. The first comprises Lum’s earlier and more familiar pieces, which experiment with how individuals convey or project identity through language conditioned by class. These include his 2001 “Shopkeeper Series,” simulacra of small business signs spelling out messages of quiet desperation in short word limits (like “SUE, I AM SORRY/ PLEASE COME BACK” beneath a sign for “Jim & Susan’s Motel”); several photographic portraits of real and fictional characters from the “Historical, Youth and Attribute Portraits” series from the early 1990s; as well as the now-iconic furniture sculpture Lum has been making since the late 1970s. The most autobiographical of these is a large installation consisting of four couches facing inward to form a square that makes sitting inaccessible. This work, Untitled Furniture Sculpture (1978–present), operates as a self-portrait of the artist and his family. Lum grew up the child of immigrant sweatshop workers and menial laborers in Vancouver, and the couches reflect the fliers for rental furniture he would collect as a child, imagining leisure and luxury in the form of overstuffed softness. He has made over a dozen iterations of these pieces by choosing couches he thought his mother would love. Lum’s insistence on retelling the anecdote of how a prominent curator questioned that anyone could possibly want a puffy couch has made his work emblematic of Bourdieuian notions of taste and class identity in contemporary art.

The “Historical, Youth and Attribute Portraits” and “Shopkeeper Series” work out these questions of aesthetic expression and class in a different register, imagining how to represent subjects—all imaginary characters, projected and constructed from a two-dimensional image-text artifact—using their own visual language and material culture. Lum’s concerns here are identity and the posing, positioning, and situating of subjects. Wattis curator Kim Nguyen has suggested in the exhibition catalog that Lum’s relationship to the art world is one of posing and posturing within—or on the outskirts of—the contemporary art world’s fraudulence at smoothing over these crucial differences.

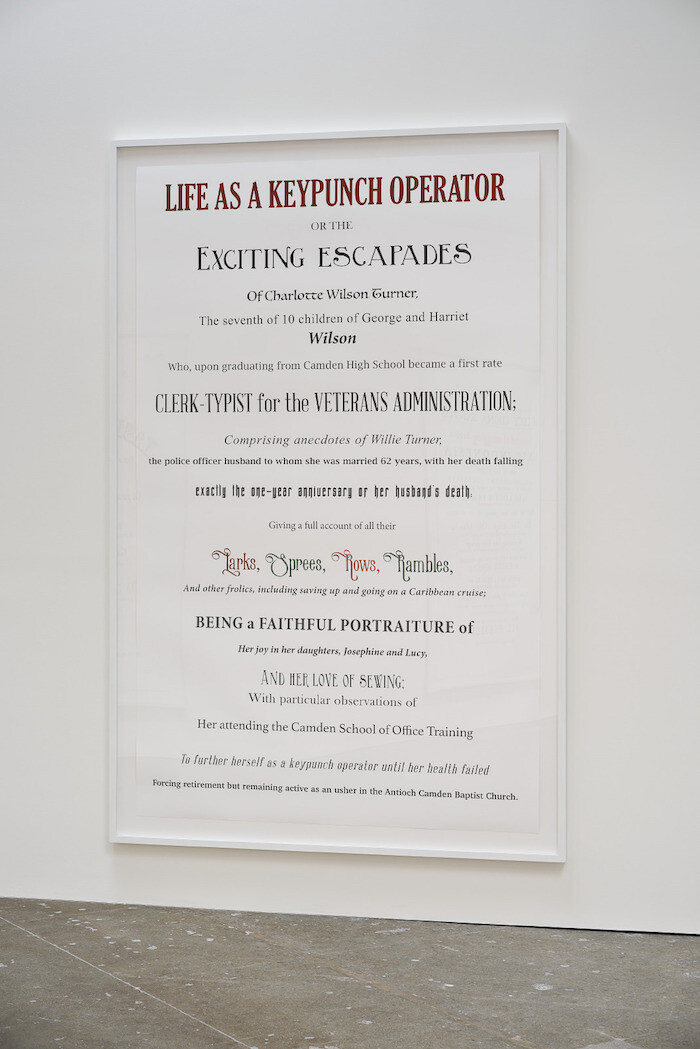

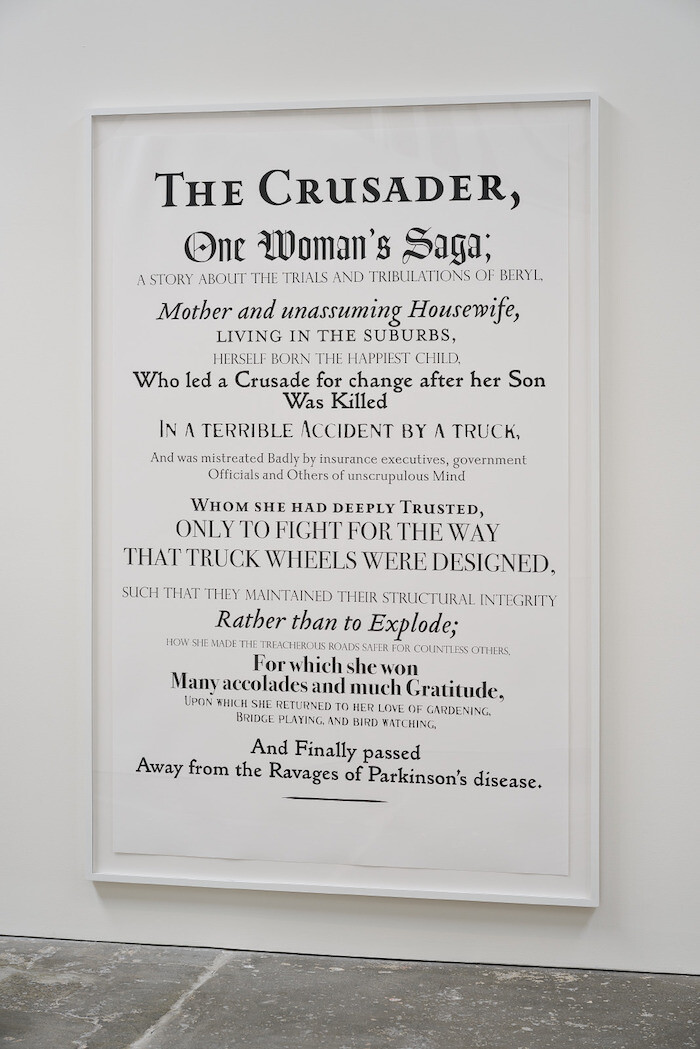

Taken together, this first gallery embodies the tropes that Lum has become most known for—including the semiotics and construction of identity via class, race, and gender—and how these factors inscribe subjects as power relations. The second set of works, explicitly devoted to memorializing the dead, is jarring to come upon after this vivid sociological critique of class performance. “Necrology” (2017) is a series of giant posters depicting fictional obituaries written in the style of eighteenth-century title pages printed in muted cream, blood red, and black with elaborate typesetting. These hang next to busts titled “Tragic Philadelphians” (2015), somber icons of troubled lives and background trauma. While this new work continues Lum’s interest in overlooked characters, the mood is distinctly bitter and ironic: the obituaries describe pathetic or banal deaths, and the busts include those of people most famous for the brutal way their lives ended.

How can this new extended meditation on death be thought of productively alongside Lum’s earlier and, frankly, more accessible work? Thinking about the formal poses of the busts and social positioning, as well as art world posturing, I discovered that the etymological root for “pose” and “posing” comes from the French poser. Its meanings include: to place a thing in a certain location (an imaginary couch in a living room, a person in a class affiliation); to place someone or place oneself in a certain attitude or position (our wealthy white male curator as a “universal” arbiter of taste); to behave affectedly (to pretend that one’s tastes are not one’s own); and to be buried, to be dead, to rest in the grave, to bury a corpse. The same forces that direct our aesthetic impulses in life also circumscribe our death, and if Lum’s newer work is more grim and difficult, it is of a piece with, and a logical conclusion to, the previously mischievous, sweet way of investigating our imagined relationships to our real conditions of existence.