Boris Johnson, with his shambolic, lumbering presence, toddler’s hair, and talent for PR stunts and gaffes, was a lavish gift to cartoonists. So it made sense that, to mark his ousting as Britain’s Prime Minister in summer 2022, the Cartoon Museum in London should stage an exhibition laying out his extraordinary trajectory from the city’s mayor to champion of Brexit and divisive national leader. Johnson is a symptomatic as well as an eccentric figure, and this record of his presence in cartoons sheds light on wider issues with ramifications beyond the United Kingdom: the symbiosis between branded politicians and cartoonists, the bodies of populist leaders, and the role of revulsion in contemporary politics.

Cartoonists tend to fix upon those parts of Johnson’s body that generally go unmentioned in technocratic political discourse—particularly his arse. The first images the viewer encounters are fairground figures by Zoom Rockman of the kind you put your head through to be photographed (a reminder of the medieval stocks). In one of these, the user’s head appears through the arse of a flag-waving PM. And ever since his time as the Mayor of London, veteran political cartoonist Steve Bell has replaced Johnson’s face with an arse (a matter we will come back to). While Johnson’s enemies regularly accuse him of talking out of his posterior, there is more to it than that.

For fans as well as detractors, Johnson’s bodily presence, leering or charismatic depending on your view, seems inescapable. This is so even for those right-wing papers and cartoonists who were and remain broadly supportive of this savior of Brexit and the Tory party. For them, his bulk was depicted as strength, and the strange configuration of his features as signals of grit and non-conformist bravery. Such images are little seen in the exhibition (they tend to be neither comical nor great examples of the cartoonist’s art). Otherwise, Johnson’s image in cartoons may be mapped across its most common territories—the failing strong man, the clown or puppet, the animal, the prick, and finally the abject body.

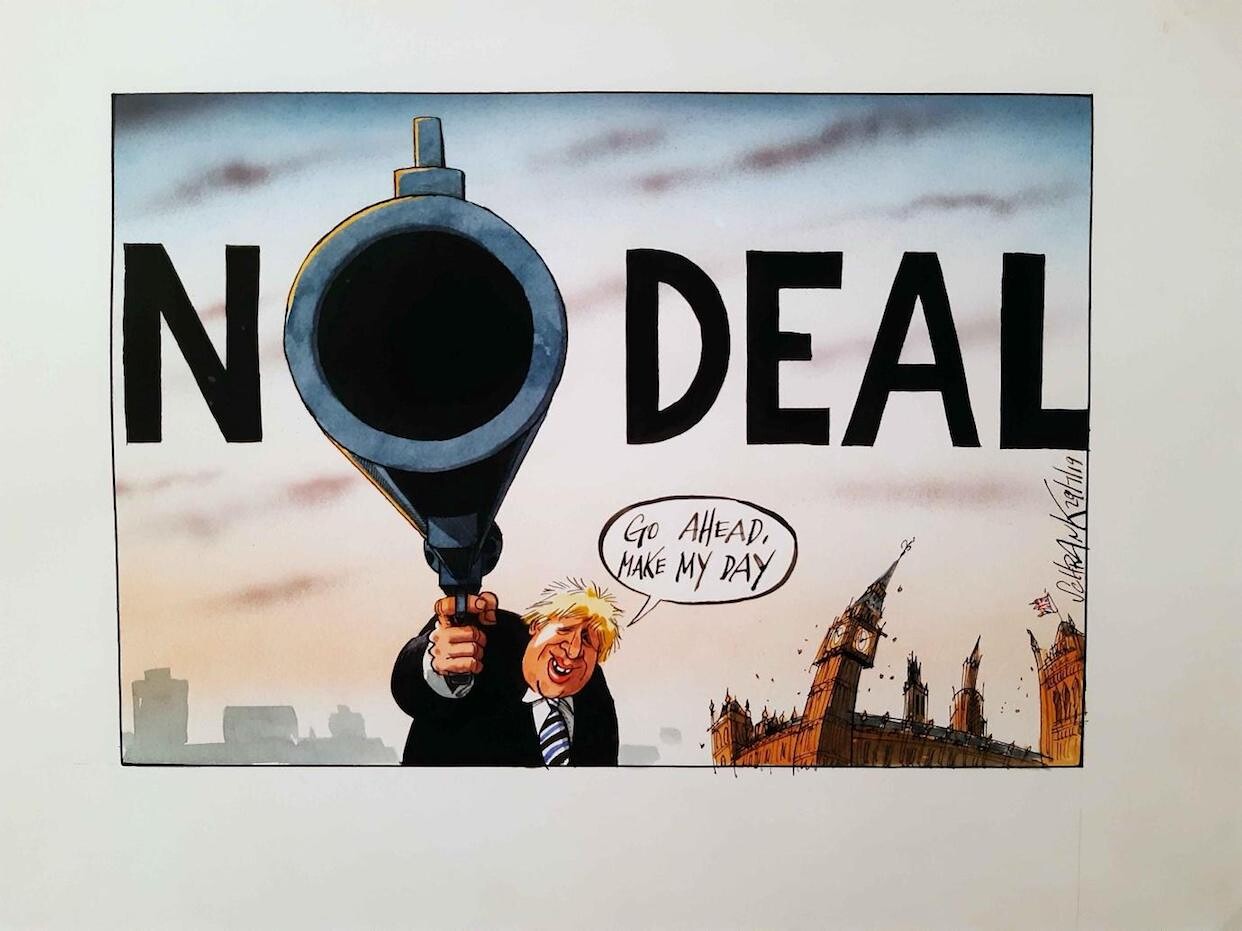

Peter Schrank, “No Deal,” The Times (July 2019). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

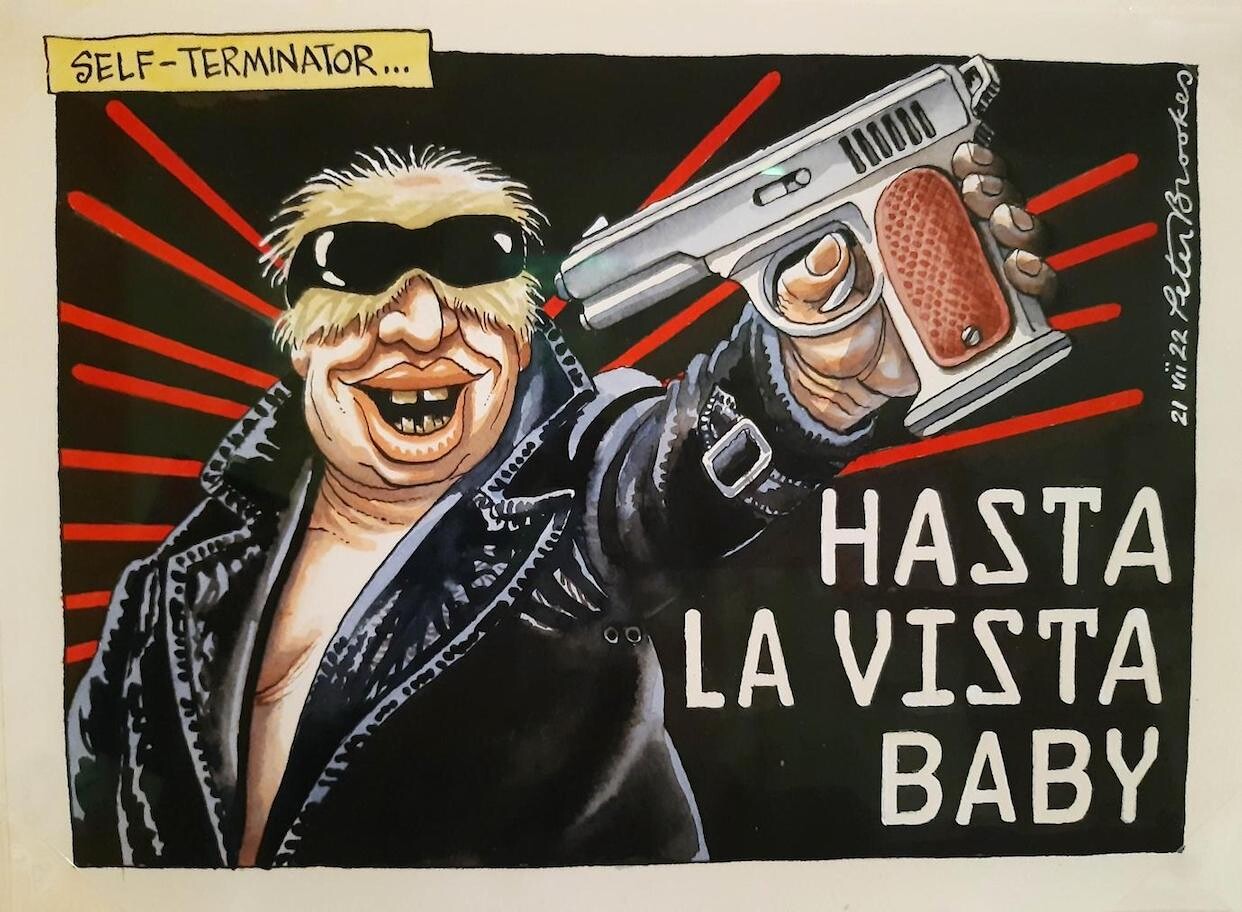

The strong man is represented by a fine curatorial juxtaposition: near the start of the exhibition, in a cartoon by Peter Schrank published in the center-right, Rupert Murdoch-owned Times, Johnson appears as an unlikely Dirty Harry. Johnson’s lardy bulk and bumbling air are very far from Eastwood’s terse and muscular form, but there is substance in comparing him to the fantasy figure of a violently authoritarian, if not fascistic, cop—the rescuer of a social order threatened by gays and Black radicals. Schrank, though, more than implies that the Brexit tremors will have the opposite effect, as bits start to fall off the Parliament building. Near the end of the show, as Johnson’s fall from Tory grace is laid out, Peter Brookes portrays the PM in the same newspaper as an equally unlikely Terminator, blindly turning the gun on himself.

Peter Brookes, “Hasta la Vista Baby,” The Times (July 2022). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

In another common move, Johnson is frequently seen as an animal—as King Kong weakly flexing and dangling from Big Ben (Christian Creseveur), as a toad (Louisa Buck modifying the parable of the frog and the scorpion), as a pig (Neville Astley), and even as the Covid virus itself. Rendering political leaders as animals is hardly a novelty, but the frequency of these moves is again associated with Johnson’s overtly bodily brand, and the uncontrolled nature of his actions and appetites which, with the inevitability of a trouser-dropping farce, led to his downfall. In a reference to the infamous Downing Street binges that broke lockdown rules, and Johnson’s absurd attempts at self-justification, the show is called “This Exhibition is a WORK EVENT!”1

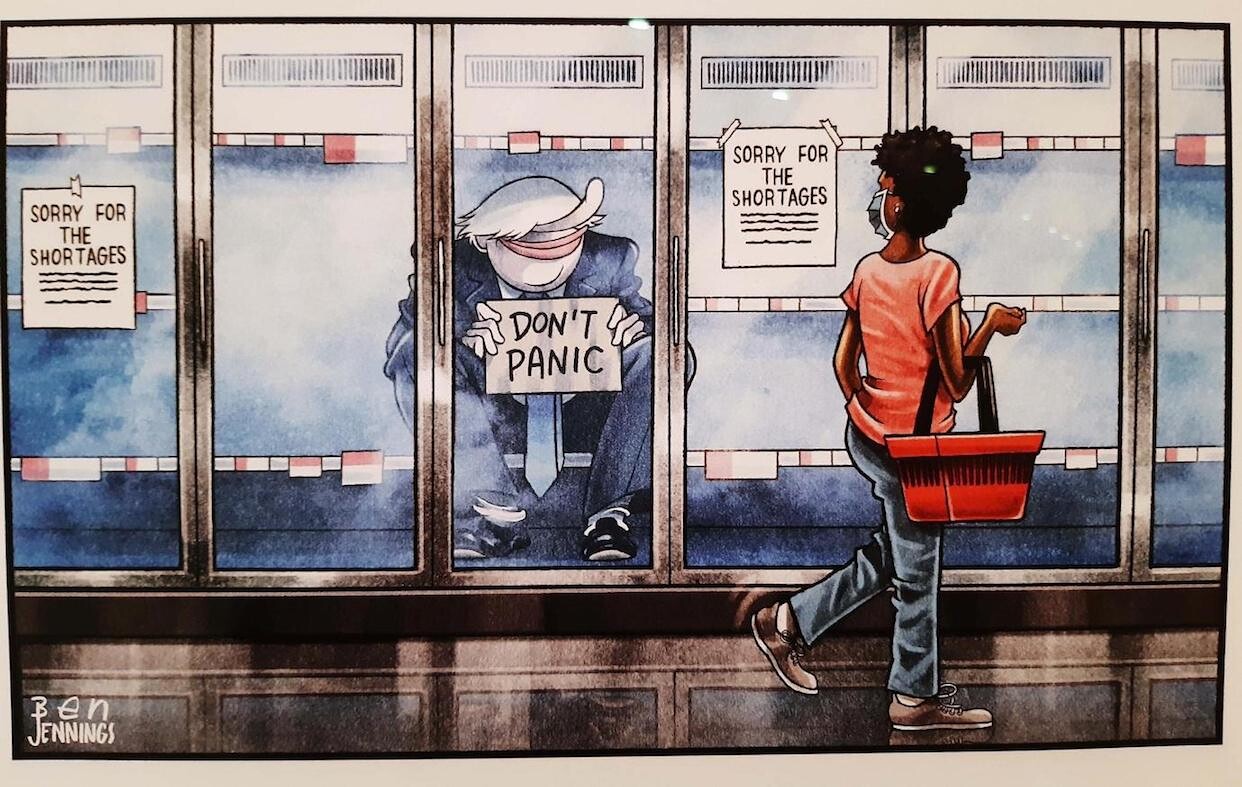

Ben Jennings, “Don’t Panic,” The Guardian (September 2021). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

Johnson is often seen as a dunce, clown, or puppet—particularly, given his pathological lying, as Pinocchio. In the staunchly Labour Daily Mirror, Martin Rowson has Johnson as a bloated, monstrous and threatening clown with a forked tongue and a balloon that signals his unbridled egotism. Johnson is as well known for his philandering as Silvio Berlusconi, which he likewise openly flaunts (in a rare criticism of his hero Churchill, he bemoans the paucity of “notches on his bedpost”).2 One Johnson fan spoke of her admiration for his “balls of steel,” a typical sentiment. While Johnson’s member is mercifully unrepresented in this exhibition, there are plenty of substitutes. In Ben Jennings’ comment on Brexit-induced food shortages in The Guardian, Johnson is seen squatting in an empty freezer, ogling a passing woman shopper, towards whom he points his curving, phallic nose, while a long tie dangles between his legs.

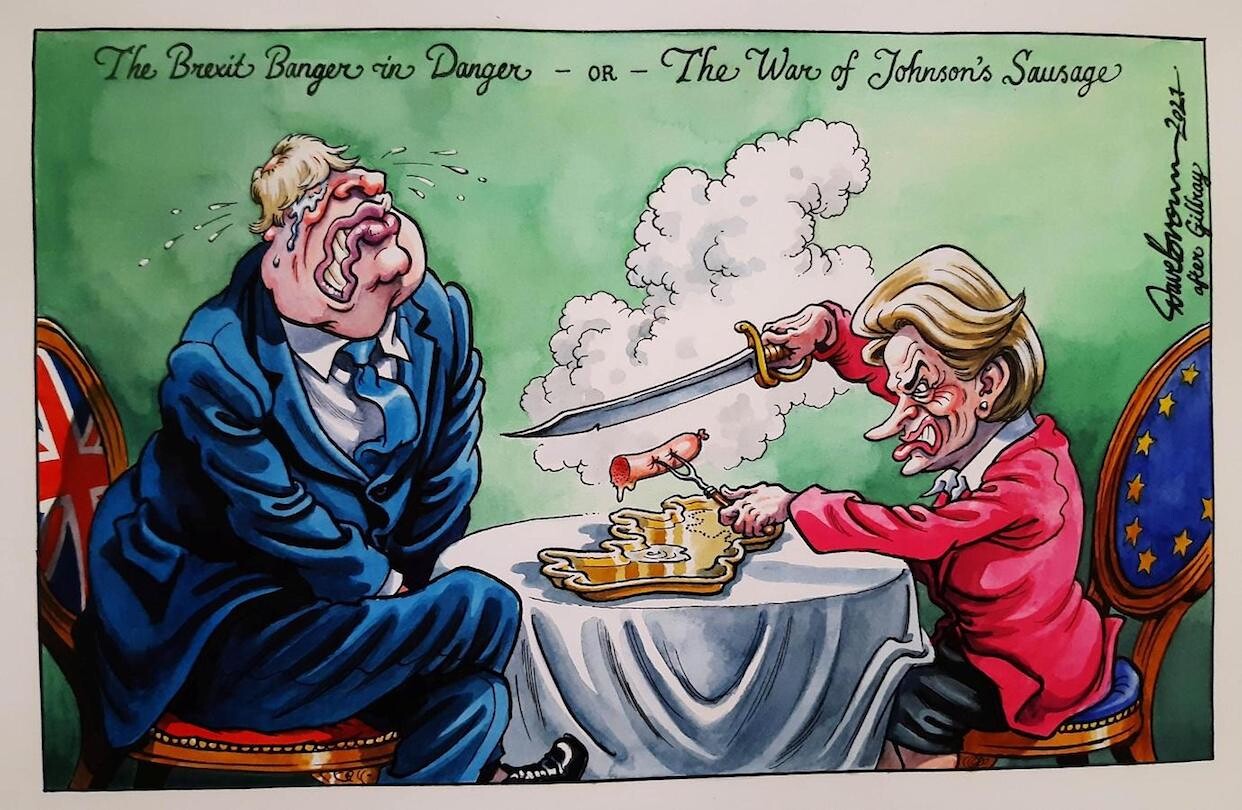

Dave Brown, “The Brexit Banger in Danger (After Gillray),” The Independent (June 2021). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

Johnson’s phallus most obviously appears in a cartoon by Dave Brown, published in The Independent, about the fiasco over Brexit and Northern Ireland, in which Ursula von der Leyen cuts into a sausage while the PM clutches his crotch. This modifies a famous cartoon by James Gillray, showing William Pitt the Younger and Napoleon as powerful and voracious imperial gluttons carving up the globe between them. In Brown’s cartoon the power relation has plainly changed. Given the strength of newspaper culture in the UK, at least until recently, the uninterrupted if highly imperfect history of its democracy, and the persistence of its hierarchy (the old regime, one might say), political cartooning has a strong tradition which current editorial cartoonists regularly invoke in echoes and references that go back to Hogarth.3

Martin Rowson, “Tory Puke,” the Daily Mirror (September 2019). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

And then there is the abject, of which Rowson is the most determined exponent, as a way to symbolize the farcical chaos of British politics since the Brexit referendum. His cartoons make political corruption physical: characters wade, dazed and disoriented, in a morass of filth which leaves no surface untainted. In one image, Johnson is portrayed as a pool of fetid muck, which is gazed into by characters from the Great Depression on their way to a food bank. In another impressive image, Cameron vomits up May who in turn vomits up Johnson (it is extraordinary that since this was drawn in 2019, two more nauseous figures could be added in).

Again, such moves are not novel. We may think of the satirical British television show Spitting Image and its endlessly abject political puppets, Steve Bell’s portrayal of Ronald Reagan, who dangles Margaret Thatcher close to his mouth in an echo of Goya’s Saturn devouring his children, or even Philip Guston’s renderings of the vile Richard Nixon as hairy male genitalia. Rowson self-consciously works in the tradition of Ronald Searle, Gerald Scarfe, and Ralph Steadman, who similarly besmirched the corrupt politicians of their day.4

Yet populist divisions have added a darker dimension to such disgust: for the right-wing papers as they depicted Jeremy Corbyn, and for the liberal and left as they depict Johnson, the expression is not merely of political difference but visceral repulsion. It bears on Bataille’s formless, which is in part a fear of the unwashed lower orders, and on Kristeva’s abject (one of her key examples being the nakedly vulgar, self-loathing fascist, Céline).5 Johnson, after all, is a chimerical figure who disrupts rational categories: an Etonian populist, a libertine defender of the Tory moral order, a traditionalist agent of chaos.

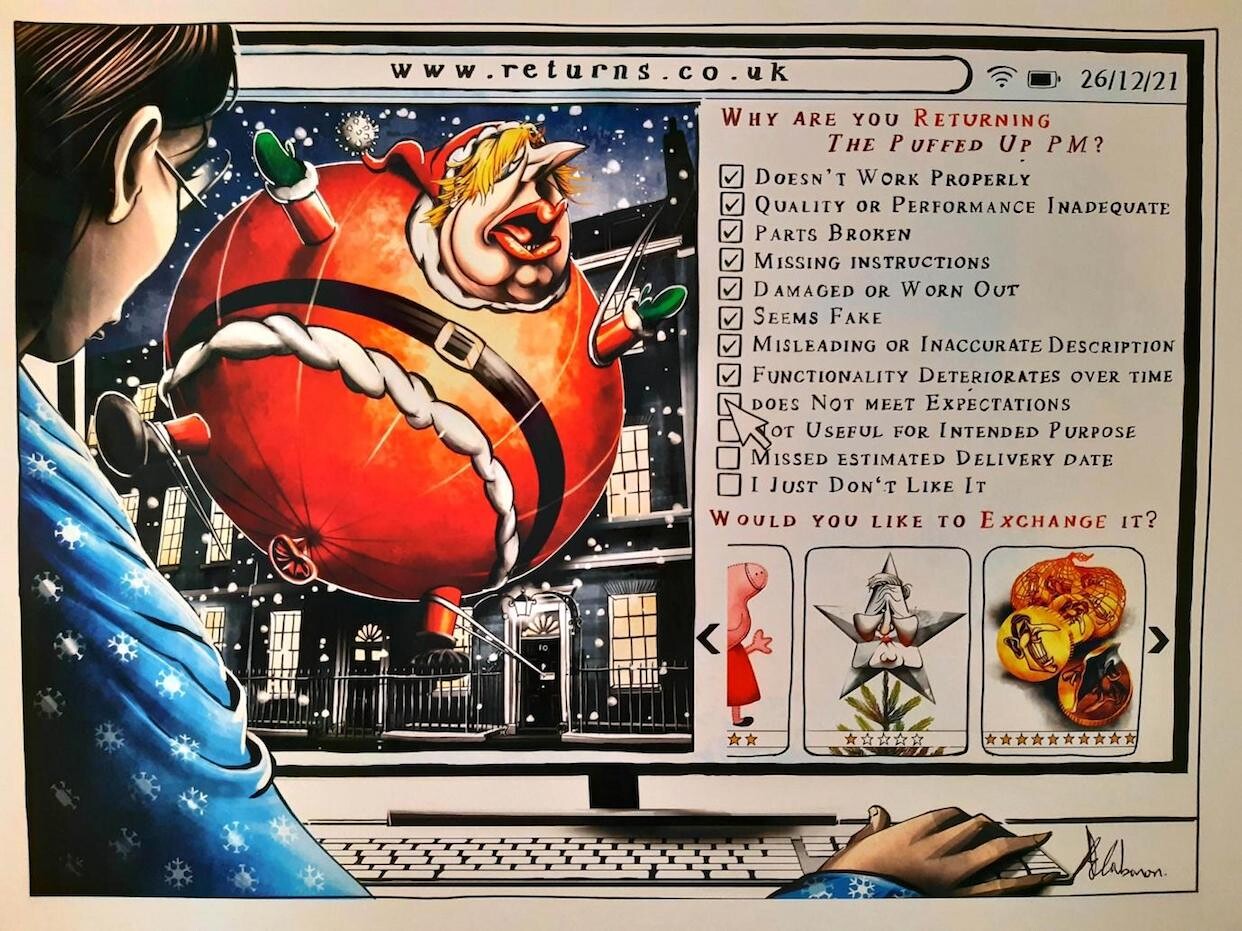

Ella Baron, “The Puffed-Up PM,” The Sunday Times (December 2021). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

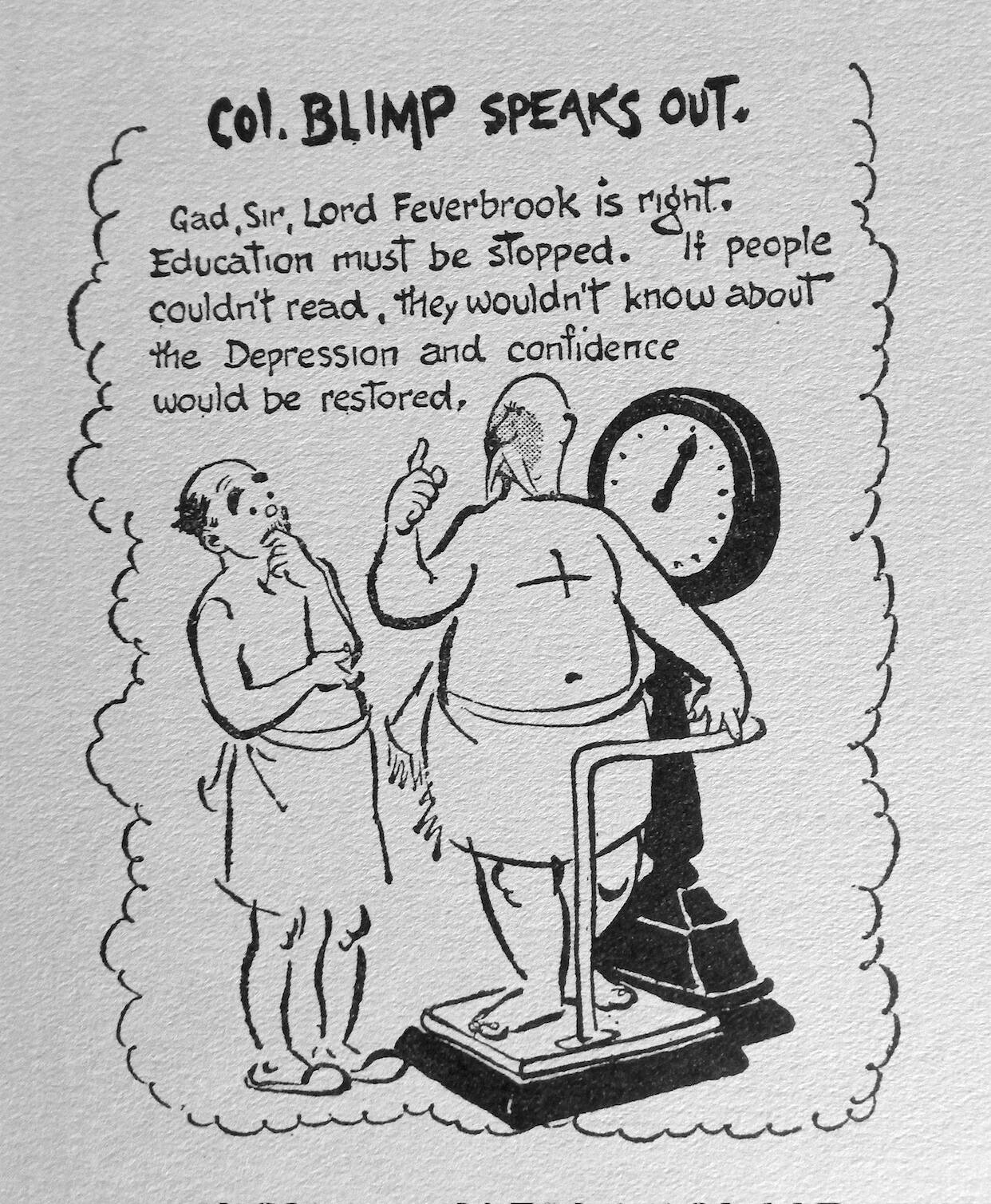

When Ella Baron depicts Johnson the gasbag as an outsize party balloon, it is perhaps a reference to David Low’s most celebrated character of the 1930s, Colonel Blimp. Low, a New Zealander, turned an amused and critical eye on the many foibles and defects of the British establishment: his Blimp was another excessive body on show, usually seen in the bath house, and inhabited by a crusty warrior of antiquated opinions, bellicose and obtuse, with an unwittingly paradoxical turn of phrase.6 The parallels with Johnson are striking, and many of the old Tory airings of prejudice can be heard in barely modified form today (in the example below, education has become an increasingly effective vaccine against voting Tory, and is subject to open government attack).

David Low, “Colonel Blimp,” ca. 1934. Public domain.

All of this bears on the enigma of Johnson’s persona, that bumbling figure of disheveled charisma (for those who buy into it), like a character from P.G. Wodehouse. This persona is highly calculated: the political journalist Jeremy Vine describes a dinner at which Johnson was the guest speaker, showing up late and apparently unprepared before stumbling into a series of amusing rhetorical moves that captivated his audience. Vine was deeply impressed until, at another dinner some time later, he had to sit through exactly the same performance.7 Image is essential to that persona, and here cartoonists—even when hostile—are of use to any politician wanting to further their brand. The symbiosis has a long history; we may think of Low’s relationship with Churchill, who was another careful cultivator of image through repeated cliché (the cigar, the V-for-victory sign, the dogged expression).8 There is tragedy and farce aplenty in Johnson’s cosplaying of Churchill: the latter, it is true, was the maker of many a disaster (of which the Bengal Famine was among the worst) but also a serious intellectual who had a sustained if noxious political project in his defence of the British Empire. By contrast, Johnson is an opportunist with few convictions whose pandering to Tory Party’s nostalgia for the grandiose imperial ghost has trashed any lingering British international influence.

In all of this, the pessimistic thought occurs that editorial cartooning, itself in decline along with the print media, makes little difference to politics, and is here fenced in by the very force of Johnson’s self-branding. Jokes about Johnson’s philandering and unknown number of offspring, for example, which are very common, only help to reinforce the Don Juan aspect of his brand.

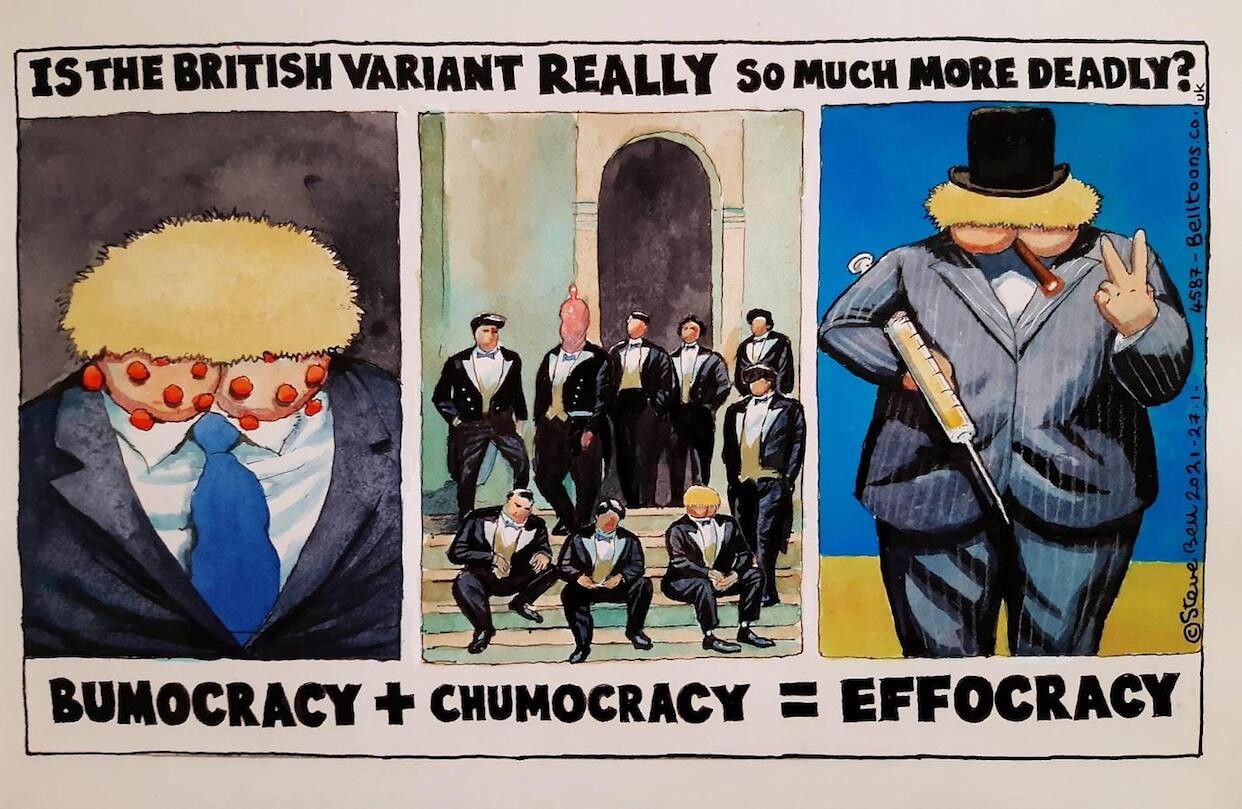

Steve Bell, “Effocracy,” The Guardian (January 2021). Image courtesy of the artist and the Cartoon Museum, London.

Steve Bell’s apparent puerility—his obsession with bums, toilets, fetish gear, and condoms—is meant to break open the branded persona (David Cameron apparently detested the condom-wearing character that Bell had dreamt up for him). In his most effective cartoons, political acuity meets such puerile subject matter. In this example, Johnson’s Bullingdon Club days are visualized in the middle panel, while the face-arse becomes the virus, and the V-sign an obscenity.9 During the pandemic, Tory donors and other hangers-on were hastily awarded huge contracts to supply medical equipment to the British National Health Service: they shamelessly profiteered from the crisis, while providing substandard goods—to deadly effect.

Johnson’s distinctiveness opens onto a wider set of conditions. When we think of other male authoritarian populist leaders, many project an excessive physicality, either with sheer bulk or muscularity: this is true of Trump, Putin, Berlusconi, Modi (who boasts of his chest size)—and also of that great Italian “athlete” Mussolini. Cartoon critiques of some of these figures would prove dangerous for the artist, but where they are permitted, bodily excesses abound; Beeple’s contemporary depictions of Trump are a telling example. The women leaders of authoritarian populism, by contrast, tend to project power through dress rather than bodily presence: think of Thatcher, Le Pen, Meloni and Weidel.

An animation by Fred Campbell shows Johnson at a press conference turning into a skeleton as he rambles on about how he shook hands with hospitalized Covid patients. Since this is on a short loop, the show is pervaded with Johnson’s voice incessantly spouting nonsense—in a troubling condensation, for those living in the UK, of the experience of the last three years. This glib, prolix, specious discourse, armored with the distinction of accent and diction, has sometimes been described in fiction. Not so much in Wodehouse, whose heroes may be charmingly hapless but are generally well-meaning, but further back.

Indeed, you might say that the Johnson persona was x-rayed in Henry Fielding’s The History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathan Wild the Great (1743), and again in George Meredith’s The Egoist (1879): in both, the superficial appearance of charm and fluency, backed by high birth, allow monstrous figures to bend the world to their corrupted will. They are aided by those who are in thrall to the aristocratic order, and over-fond of a good drink. In both novels, the characters eventually meet their doom or at least humiliation, and proper order is restored. Despite Johnson’s temporary downfall, and given the wider march of the populist right, we can be much less sure of the real world.

“This Exhibition is a WORK EVENT!” is on view at the Cartoon Museum, London through April 16.

During the pandemic, and in breach of lockdown rules, regular parties were held at Downing Street. Although some went on into the early hours and involved heavy drinking, they were defended by Johnson as work events. Johnson was eventually fined by the police for one such breach.

Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2014).

Arno J. Mayer, The Persistence of the Old Regime: Europe to the Great War (London: Croom Helm, 1981).

Martin Rowson, “Ronald Searle was our greatest cartoonist – and he sent me his pens,” The Guardian (3 January, 2012), https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/jan/03/ronald-searle-sent-me-his-pens.

Georges Bataille, Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, ed. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985); Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

The famous film version by Powell and Pressburger has as its protagonist an old-fashioned but romantic, good-natured and noble fellow who is far from the cartoon original. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, 1943; Low notes the transformation in Low’s Autobiography (London: Michael Joseph, 1956), 273.

Jeremy Vine, “My Boris Johnson story,” The Spectator (17 June, 2019), https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/my-boris-johnson-story/.

Low’s Autobiography, 159-60.

The Bullingdon Club was and is a boorish drinking club for well-connected right-wingers at Oxford University.