Santiago Mostyn has placed low banks of sand at rhythmic intervals throughout the large, open exhibition space of Södertälje Konsthall. Brazil nut casings lie scattered on top of the sand; they are also suspended from the ceiling, each shell holding a speaker. A soft clicking animates the room, as the eighteen-channel sound work emanating from the shells thickens the space at the periphery of my senses, like a subliminal awareness of thriving insect life. Looking down, I notice that viscous liquid fills one of the empty shells to resemble brackish rainwater trapped at the bottom. One shouldn’t leave water standing in the tropics, it invites mosquitoes to breed, I think, and realize that my mind has left the outskirts of Stockholm.

The floor beneath Mostyn’s piles of sand is a permanent artwork by the design duo Laercio Redondo and Birger Lipinski, entitled Opacity (for Édouard Glissant) (2021). Inspired by indigenous weaving techniques in the Americas, it is an abstract geometrical pattern made with rectangular flooring panels in beige, navy, and powder blue. The design reminds me of a disarticulated Catholic labyrinth, a geometric pattern inlaid in stone on the floor of cathedrals during the Middle Ages, that provided a score for perambulatory meditation. Mostyn’s installation of sand and Brazil nut shells floats above this bizarrely named intervention, neither confirming nor denying its right to claim Glissant’s legacy. And this distanciation works—it creates a pause between the work on view and its institutional foundation. It evokes the dream state.

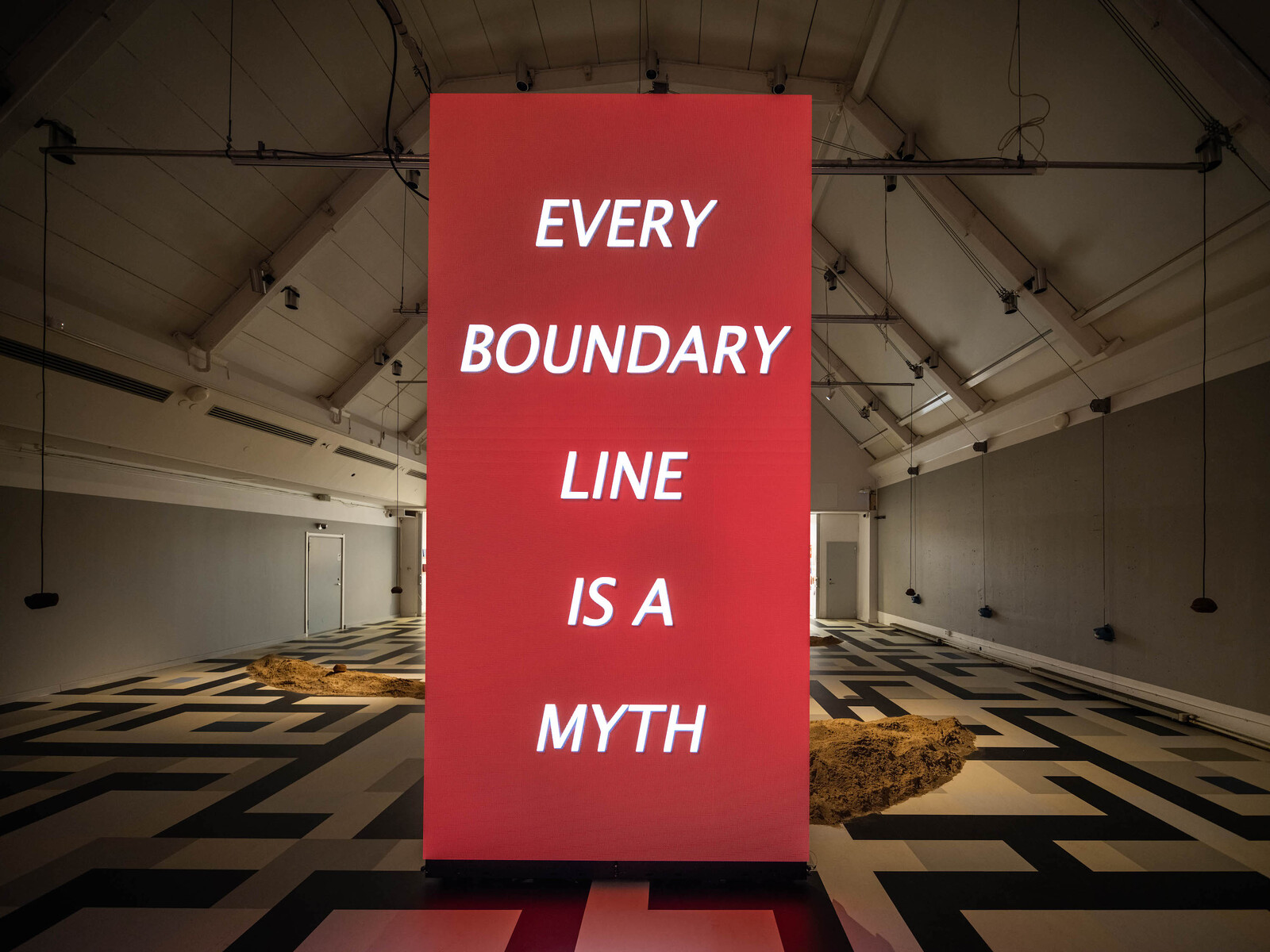

In the center of the exhibition hall is a flat dark form with the dimensions and inscrutability of the infamous monolith from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). As I approach, I realize that this intimidating stele is composed from the back sides of LED screens. A video plays on the front, rising from the piles of sand and the geometry of the floor installation with the intense glow of an animated advertising billboard in public space—luminous and visually inescapable. Again, I am struck by the choreography of Mostyn’s installation, the way it engages all the senses so that the viewer is prepared to submit to the moving image completely.

I enter the video loop during a scene in which a slender mushroom is slowly growing towards the top of the screen. When it reaches its full height, the fungus begins to wilt under the weight of its own cap. On the voiceover, someone is telling a story of warning; do not call the names of your children, lest the Trinidadian spirit-creature called the douen learns their voices and calls their children into the forest, never to return. The pattering rhythm of the surrounding sound installation deepens the soft feeling of threat in this fable about speech.

In the video’s first scene, an older man’s gravelly voice casually asks an unseen interlocutor, “You writing these days?” as large palm trees sway against a darkened sky. Unspoken sentence fragments appear on screen in response: “Trying to … This thing about loss … about the failure to return.” The image beneath these lines is almost abstract, a close panning shot tracing the length of a branch, unanchored in time and place. The shot cuts abruptly as the older man’s voice breaks out in a gruff, dismissive guffaw. “You think we have time for the burden of history?” he asks, enunciating each word precisely to make sure his scepticism is understood. “The sigh of History rises over ruins, not over landscapes,” he intones, quoting St. Lucian poet Derek Walcott.

On one level, this scene is Mostyn’s story, articulating his own sense of failure in returning to Trinidad after having lived several other kinds of lives. Born in San Francisco in the early 1980s, Mostyn grew up in Zimbabwe and in Trinidad & Tobago; he studied art at Yale, then spent a year descending the Mississippi River. Though based in Sweden since 2011, where he took an MFA at the Royal Institute, Mostyn’s practice revolves around the impossibility of any definitive belonging. “Dream One” is filmed in Trinidad, but the fragmentation of image and speech admits that being there is not the same as returning.

In A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes on Belonging (2001), Canadian poet Dionne Brand writes, “This existence in the Diaspora is like that — dreams from which one never wakes. … A set of dreams, a strand of stories which never come into being, which never coalesce.”1 This failure to coalesce, to find the horizon or the ground, is fundamental to Mostyn’s “Dream One.” The work also, for me, deepens my own sense of loss in encountering Walcott’s immense poetic legacy—so important for Mostyn, but also for Brand and many other Black poets —in light of the accusations of sexual harassment against him from a former student. Walcott re-drew the map, providing a way to conceptualize history outside the imperial center. But does a map that has been redrawn by a man accused of diminishing women allow for return, in that deeper sense to which Mostyn and Brand refer? This question marks a place where the fault lines of belonging and threat cross and re-cross, and “Dream One” succeeds in resisting a clear or stable answer.

Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes on Belonging (Vintage Canada, 2017), 45.