June 11–27, 2021

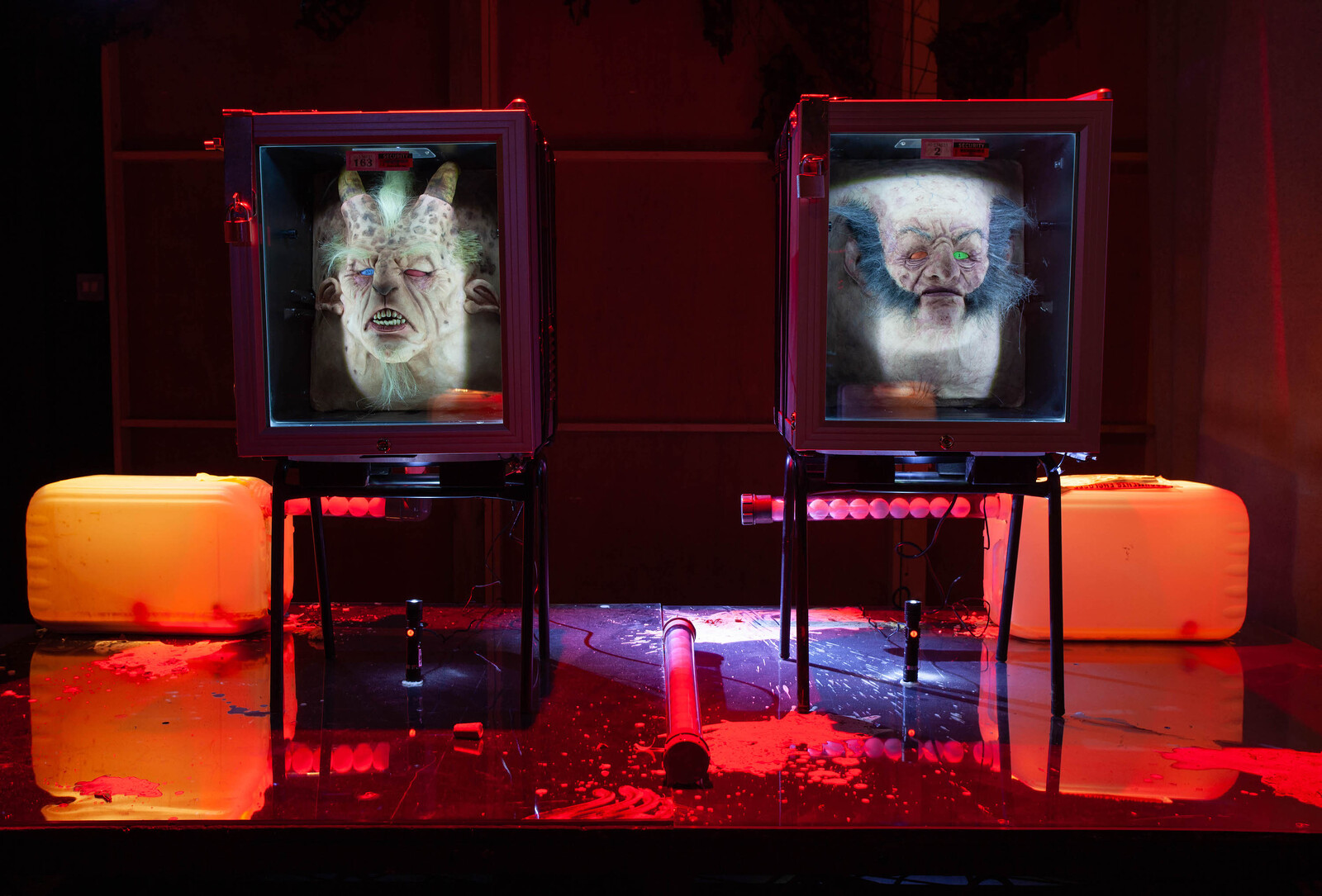

On my way to Tramway in Glasgow’s Southside I spot the artist Jenkin van Zyl walking past the McDonald’s on Pollokshaws Road. I know it’s van Zyl because I watched an online video about his make-up routine.1 He’s wearing prosthetic horns, hooks for hands, and nothing much on the bottom half, except for some strapping that reveals pretty much the whole of his arse. Van Zyl’s film Machines of Love (2020–21), showing at Tramway as part of Glasgow’s biennial arts festival, unfolds like a World of Warhammer cosplay fantasy with heavy shades of Paul McCarthy, in which a group of orc-like people with rat teeth and squashed noses conduct squalid sex games in an underground lair. The prosthetics are impressive, yet while van Zyl has understood the look, after 40 minutes of writhing around it’s less clear what he wants to say with it: a problem endemic in a culture that specializes in polishing and grafting pre-existing aesthetics.

The theme for this year’s festival is “attention.” During an era in which convoluted curatorial agendas have become de rigueur, director Richard Parry has opted for the opposite approach, picking one so open that you’d be hard pressed to find an artwork to which it couldn’t be applied. (Parry explains that it could refer to the attention economy, paying attention to materials or to historical or current affairs.) There is an inevitable irony about not knowing what, exactly, viewers are supposed to pay attention to, yet, despite my misgivings about the one-size-fits-all nature of the theme, the curation is commendably generous. Each artist has been given plenty of room, and, happily, the festival is free of group shows attempting to shoehorn varied artworks into Byzantine theses.

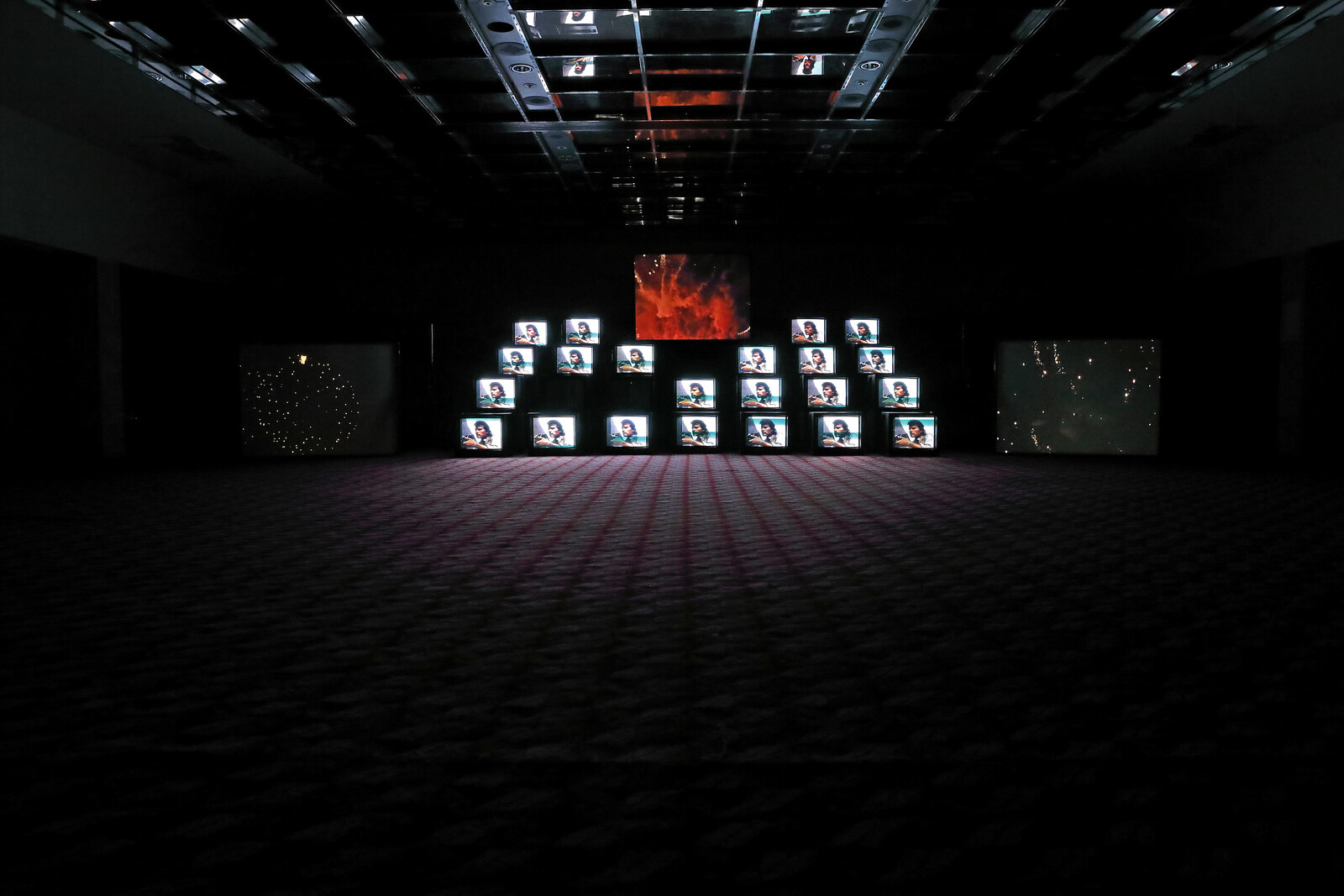

The festival’s core program involves 12 artists exhibiting in venues across the city. Outside Glasgow Sculpture Studios, I lie on an inflatable cushion and watch business as usual: hostile environment (2021) by Alberta Whittle. The film connects the pandemic, the Windrush scandal, and UK immigration policy, drawing attention to the frontline workers who face deportation because their annual salaries don’t meet the financial threshold required to get a work visa. It’s screened on the side of a van, Whittle tells me, in order to echo the Home Office “Go Home” vans, driven around the UK in 2013 as part of the Conservative government’s “hostile environment policy.”2 Gretchen Bender’s Total Recall (1987) is on show at The Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, a montage of television and film footage played across 24 monitors, and a prescient vision of our current domination by the media matrix. At Barrowland Ballroom, Duncan Campbell’s o Joan, no… (2006) is screened beneath the mirror balls, a 12-minute film of a woman grunting and sighing accompanied by flashes of light.

Despite the quality of much of the work, at times the heavy presence of film can feel like an endurance test for a niche type of masochist; it also has unfortunate echoes of a year spent heavily reliant on screens. This made Paul Maheke’s live performance at SWG3 on the opening night all the more moving. Maheke walked into the hall in satin shorts and knee pads, and began dancing on his toes like a nervous boxer. As he jabbed and trembled, he seemed to channel the anxiety that has gathered over the past year and shake it out of his system. Running alongside the core content is the larger Around the City Programme (ACP), an array of events and exhibitions staged by artists, galleries, and other organizations. Participants, who must be based in Glasgow, are selected for inclusion by a panel of artists and curators assembled by the festival, and provided with funding of up to £10,000. As in past years, the ACP doubles up as an excellent introduction to the Glasgow scene, from commercial galleries to DIY spaces. At The Modern Institute, Eva Rothschild’s slick, abstract sculptures fit into the category of “lobby ready” art, easily transposed from gallery or art fair to cavernous atrium. The program really shines when it takes viewers out of white cubes and into venues embedded in the life of the city. At the Glasgow Women’s Library, a local institution that exists under the perennial threat of closure, Ingrid Pollard has made an exhibition from the lesbian archive in the library’s holdings. Speakers have been added to bookshelves, through which visitors can listen to the oral histories of women involved in community organizing. The festival’s stand-out exhibition, and also part of the ACP, is at Celine: an artist-run gallery in a top-floor tenement flat in Govanhill, a neighborhood where many of the city’s artists and writers live.

Celine is scruffy inside, but (typical of the tenements) there is a grandeur to the architecture, with its high ceilings and fancy cornicing. On show are works by and about the artist Donald Rodney, a member of Britain’s BLK Art Group who died from sickle-cell anemia in 1998. In a room with stained carpets and dodgy wallpaper, accompanied by a friendly cat, I watch Three Songs on Pain Light and Time (1995), a documentary by Edward George and Trevor Mathison that portrays Rodney as a beloved and brilliant thinker. Also on show is the CD-ROM work AUTOICON (2000), made following Rodney’s death and according to his wishes by friends Geoff Cox, Mike Phillips, Virginia Nimarkoh, Richard Hylton, and Keith Piper. An interactive collection of interviews, audio clips, images, and medical records, AUTOICON functions as a digital memorial and a means of keeping Rodney’s ideas and experiences alive.

Places like Celine and the Glasgow Women’s Library give the Glasgow International its cultural texture and specificity. The biennial circuit can seem like the global art circus pitching its tent in different locations: roll up for the same artists, supported by the same commercial interests, viewed by the same patrons and critics in novel locations. When biennials like this one work, it’s not because they’ve proven their status by enticing internationally successfully names to participate. It’s because they’ve managed to engage the ecosystems in which they take place.

Arden Fanning Andrews, “Watch Jenkin van Zyl’s ‘Wrestler Cowboy’ Extreme Beauty Transformation,” Vogue (December 28, 2020) https://www.vogue.com/article/jenkin-van-zyl-extreme-beauty.