The new extension of Centro Pecci (designed by NIO Architecten Rotterdam, and inaugurated last fall) is a ring-shaped volume clad in golden aluminum, halfway between a UFO from a 1950s B-movie and the corporate headquarters of a German car brand, surrounded by an urban sprawl of office blocks, residential buildings, shopping malls, McDonald’s joints, and freeways. The industrial city of Prato is only a half hour from Florence by train, but miles away from the picture-perfect cliché of Tuscany as the holy land of the Renaissance—probably one reason why, back in 1988, it welcomed the first contemporary art museum in Italy, built here with the ambition of following the multidisciplinary example of Paris’s Centre Pompidou. Several decades (and a few industrial crises) later, the Pecci still looks like an alien trying to establish contact with humans.

“76’38’’ + ∞,” the title of Jérôme Bel’s current exhibition at the museum (curated by Antonia Alampi), fits well with the sci-fi mood. It corresponds to the minimum amount of time required to see the works on show from beginning till end, plus the possibility of extending the experience ad infinitum. I abided to it, so that Bel paced my steps to his tempo—larghissimo, adagissimo, lentissimo.

The film Company Company (2015, after the performance Compagnie, compagnie, 2013-ongoing), projected at the entrance in cinematic proportions, from floor to ceiling, is the pièce de résistance. In it dancers, who move across a nondescript white cube, tower over the audience, reversing the traditional stage setup for performance. But it’s hard to feel intimidated: whenever one dancer starts a well-rehearsed individual routine, to the pounding sound of pop or classical music, all the others tentatively mimic their moves, karaoke-style. The cast features ballet and tap dancers, old ladies, children, disabled people, actors, all dressed (and sometimes cross-dressed) in colorful and glittery dance gear, so that movements range from the athletic and precise to the spontaneous and clumsy, from waltzing to headbanging, reverberating in waves. Bel has used this format in other works, such as the Performa commission Ballet (New York) (2015), and Gala (2015), which made its Italian debut in Florence in May, on the occasion of this exhibition. Empathy, admiration, and good vibes ensue, along with the voyeuristic pleasure of looking at anonymous bodies in motion, each one in its own surprising way. In French as in Italian, the expression “corps de ballet” emphasizes the presence of “a community of bodies,” to quote Roland Barthes, a key point of reference for the artist.

Paris-based Jérôme Bel emerged in the mid-1990s as one of the leaders of the European new wave of conceptual dance, in the company of (and frequently in collaboration with) Boris Charmatz, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Xavier Le Roy, all invited to show projects and choreograph “retrospectives” in major museums over the past few years. They all faced the same problems: how to combine the intensity of the here and now with the presence of a fluid audience over extended opening hours, how to reproduce a unique performance, and how to comply with or resist the institutional desire to employ live arts as public attractors. All these issues resurface in Prato.

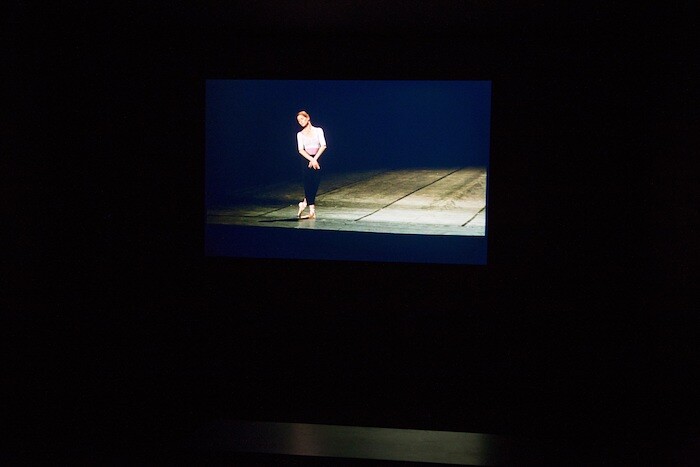

Performances like Shirtology (1997), where dancer Frédéric Seguette interprets the instructions of the graphic t-shirts he keeps on changing (“Dance or Die,” “Shut up and dance,” “Stay Cool,” “Replay”), and Véronique Doisneau (2004), where, on the night before her retirement, the eponymous dancer from the Paris Opera describes to the Opera’s own public her lifelong experience as a ballerina, are presented as autonomous films, projected on a wall or on enclosed by a large digital screen. Other works in which acting and spoken word take center stage, like Pichet Klunchun and myself (2005) and Disabled Theater (2012), are confined to small monitors in the documentary room. Every Sunday, the film Company Company comes alive as Compagnia, compagnia, performed by Prato-based amateurs, so that the same choreography and its characters morph into an energetic, site-specific, and more “authentic” version. It’s a calculated effect—despite his engagement with inclusivity, Bel steers away from improvisation. In delegated performance, Claire Bishop writes, the author outsources authenticity, so that it “is invoked, but often questioned and reformulated, by the indexical presence of a particular social group, who are both individuated and metonymic, live and mediated, determined and autonomous.”1

Danzare come se nessuno stesse guardando [Dancing as if nobody were watching] (2017), the new durational piece created by Bel for the occasion, is permanently on show, and unfolds like a device by which to interpret the museum’s architecture. In a large empty space, a solo dancer rolls and crawls across the bright pink carpeting, from one end of the room to another, as if to measure it, in a loop of decelerated gestures accompanied by the loud drone of the “natural” 432 Hertz frequency. I watched Danzare long enough to forget the clock and the phone, while Instagram feeds on the opening of Documenta in Kassel were being flooded with pics of Maria Hassabi’s Staging (2017), an equally slow performance staged on a pink-carpeted flooring. In times of a hysterical attention economy, it’s clear that dance embodies our need for a different speed of consumption. Could alienation, as opposed to forced entertainment, be the answer?

Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells (London: Verso, 2012), 237.