Earth-stuff goes through myriad transformations on its path to usefulness in our world. Soil, stone, water, oil, plants, animals, and the rest all pass through processes of cleaning, smoothing, separating, reconstituting. And at the end of that violence is an exquisite, terrifying flatness: one that expresses itself through identical buildings, garments, and foods; through the identical spaces conveyed by this screen and the identical blackness inside it.

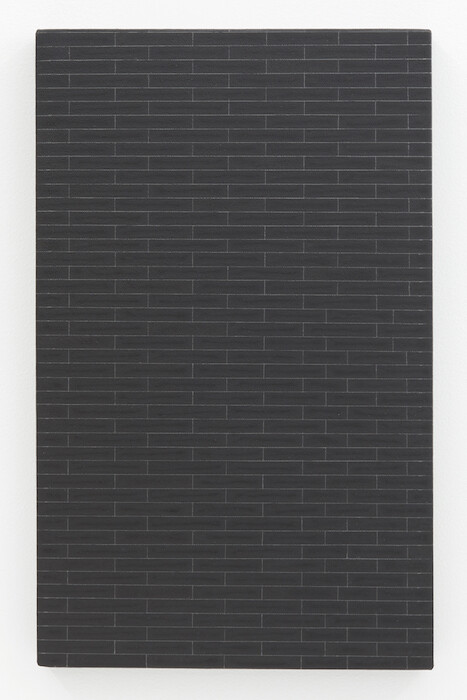

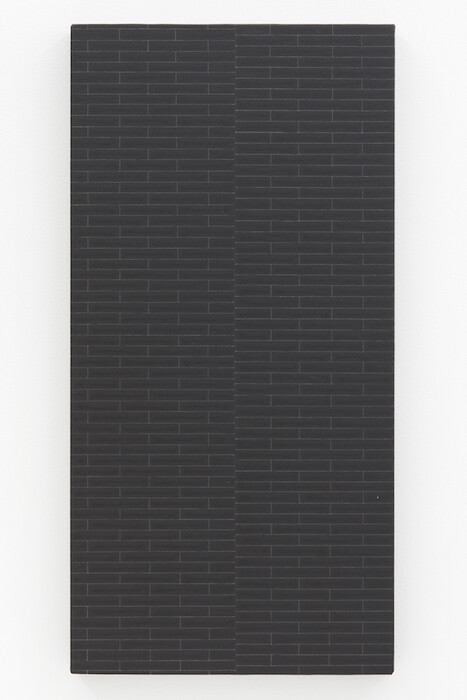

From her Manila studio, Maria Taniguchi makes work about the extraction of Earth-stuff—about its flattening and the entanglement of humans and nonhumans this transformation is contingent on. Born in the Philippines in 1981, Taniguchi works in installation, sculpture, and video, but she is best known for her nearly decade-long series of untitled paintings depicting a pattern of identical black bricks. Perhaps the plural is unnecessary: it’s really a single brick, roughly two by six centimeters, outlined in graphite on canvas or linen, and filled with black and gray acrylic. This brick repeats itself through her paintings, which seem to vary only by the size of their frame (from centimeters to meters) and the position they occupy in a gallery or studio. Her grid is uniform and endlessly scalable.

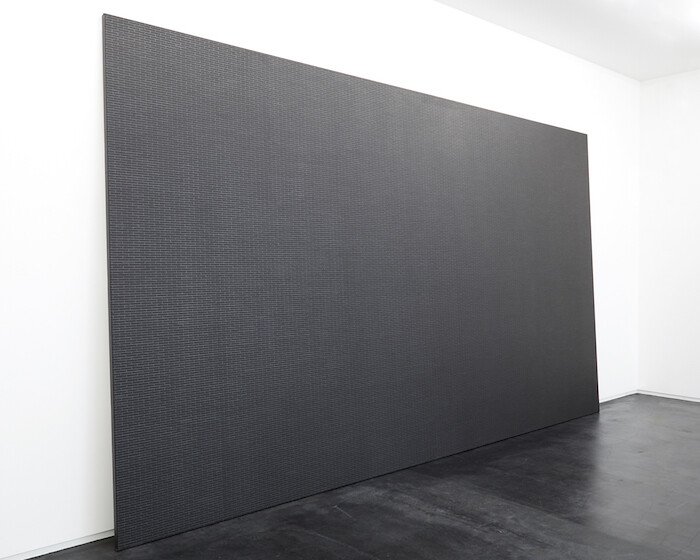

This brick helped win Taniguchi the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award in 2015, and secured her a steady stream of solo and group shows since. At Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo, in the backstreets of Roppongi, Taniguchi presents her latest series of works, all produced this year: a collection of 12 small, sparsely distributed brick paintings; Runaways, a hanging sculpture of hoops and rods made from Java Plum wood, native to Southeast Asia; and a large 3-by-5-meter brick painting stretching across—and leaning against—one wall of the L-shaped gallery.

Up close, the bricks could be a dungeon, a palace in shadow, a cobblestone path viewed from above, a red-brick factory at night, agricultural plots seen from the air, stacked packets of data, or the crystalline structure of matter. The pattern can travel in many directions: from the planetary to the microbial.

Scale is important for Taniguchi. Her flat, limitless grid enables the kind of “drastic scaling-up or scaling-down of the human point of view” that philosopher Eugene Thacker believes comes from confrontations with cosmic scales—the “unhuman orientation of deep space and deep time,” natural phenomena that create a sense of “primordial insignificance” in human observers.1 But could this scaling-up and scaling-down also appear in the confrontations with manmade manifestations of the infinite?

In their 2013 book Horror in Architecture, researchers Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing describe something similar in the modernist architecture of Mies van der Rohe, for whom the “frame itself” became a “primary organization device.”2 The surface of his buildings operated according to a “Miesian system,” they say, which “could go on infinitely”—a flatness, with all traces of extraction and ornamentation erased, with the potential to extend far, far beyond the human scale. Horror in architecture, indeed.

The 12 smaller brick paintings, carefully positioned at eye-level along the white walls of Taka Ishii Gallery, have a sense of being frozen mid-extension. In some cases the pattern appears to have reached the end of one iteration and abruptly begins another, like the oppressive facades of Tokyo apartment blocks butted up against one another. But though it’s tempting to view Taniguchi’s pattern as an abstraction of the built environment—especially for viewers in Tokyo—the act of painting serves other, non-representational purposes: “People look at these works and see abstract pictures, but in reality they serve a very practical purpose,” Taniguchi says in an interview with ArtAsiaPacific magazine from 2013. “These paintings take time and help me regulate my own production, my thinking. They set the tone for the rest of my work.”3

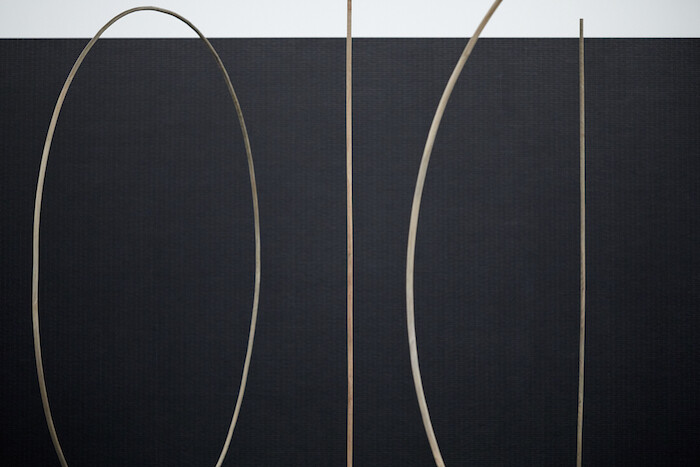

The entanglement of human workers and Earth-stuff is a recurring theme in Taniguchi’s sculptural and video work, appearing in this current show through Runaways, a sculpture of five straight rods and two large loops that hang from the ceiling with transparent wire. These Is and Os are floating representations of the on/off binary that underpins computing—the essential architectural elements of the ultimate flatness: data. But the minimalism and abstraction of Runaways is incomplete, undermined by the materiality of the wood itself—the wobbly horizontality of the wooden rods and imperfect circularity of the hoops. These details evidence the physicality of a human cutting down the tree it came from, and the labor of the other people involved in transforming that material into the shapes that we see in the gallery. The messy environment that generated Runaways inserts itself into the abstraction.

Timothy Morton writes that “environmental awareness might have something intrinsically uncanny about it, as if we were seeing something we shouldn’t be seeing, as if we realized we were caught in something.”4 An environmental anxiety lurks in the formal cracks of Taniguchi’s paintings and sculptures—in the Java Plumness of the hardwood, in the subtle variegation of the bricks (traces of the moments when she added more or less acrylic while laying over the canvas), or through the changing thickness of her outlines. Small traces of human involvement are what gives the work tension as it reaches, in vain, toward a limitless flatness.

These works are not anonymous modern objects, though they attempt that transformation. They’re objects made by a named person—someone who has spent almost a decade laboring over an uncreative, unexpressive, unreasonable pattern. The formal and conceptual cracks are where we see what her abstractions, and the material abstractions around us, are contingent upon: humans transforming Earth-stuff. These cracks are much harder to locate in iPhones, H&M garments, prefabricated houses, Muji slippers, Miesian systems, and quantum computers.

Taniguchi’s work may be dry, but it’s not equanimous. There’s something slightly unnerving about peering through the cracks in an “unhuman” grid and glimpsing people, soil, stone, water, oil, plants, and animals.

Eugene Thacker, Cosmic Pessimism (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2015), 13.

Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing, Horror in Architecture (ORO Editions), 39.

Marlyne Sahakian, “Where I Work: Maria Taniguchi,” ArtAsiaPacific, June 25, 2013: http://artasiapacific.com/Blog/WhereIWorkMariaTaniguchi.

Timothy Morton, The Ecological Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 58.