A guide, dressed all in black, formally addresses the audience. Argentinian artist Valentina Diaz’s practice, the guide explains, relies on a series of inexact but exacting translations: specific mental states inspired hand-knitted costumes; knitting patterns are transposed into a musical score rendered on an old-school typewriter; this score is interpreted, according to a tempo kept by a metronome, as a choreography for performers dressed in the costumes. Diaz’s performances have long been characterized by such iterative mutations, a methodology emphasized in this exhibition: rather than wander around the space, viewers enter at specific times to follow the guide through a pre-planned sequence of rooms.

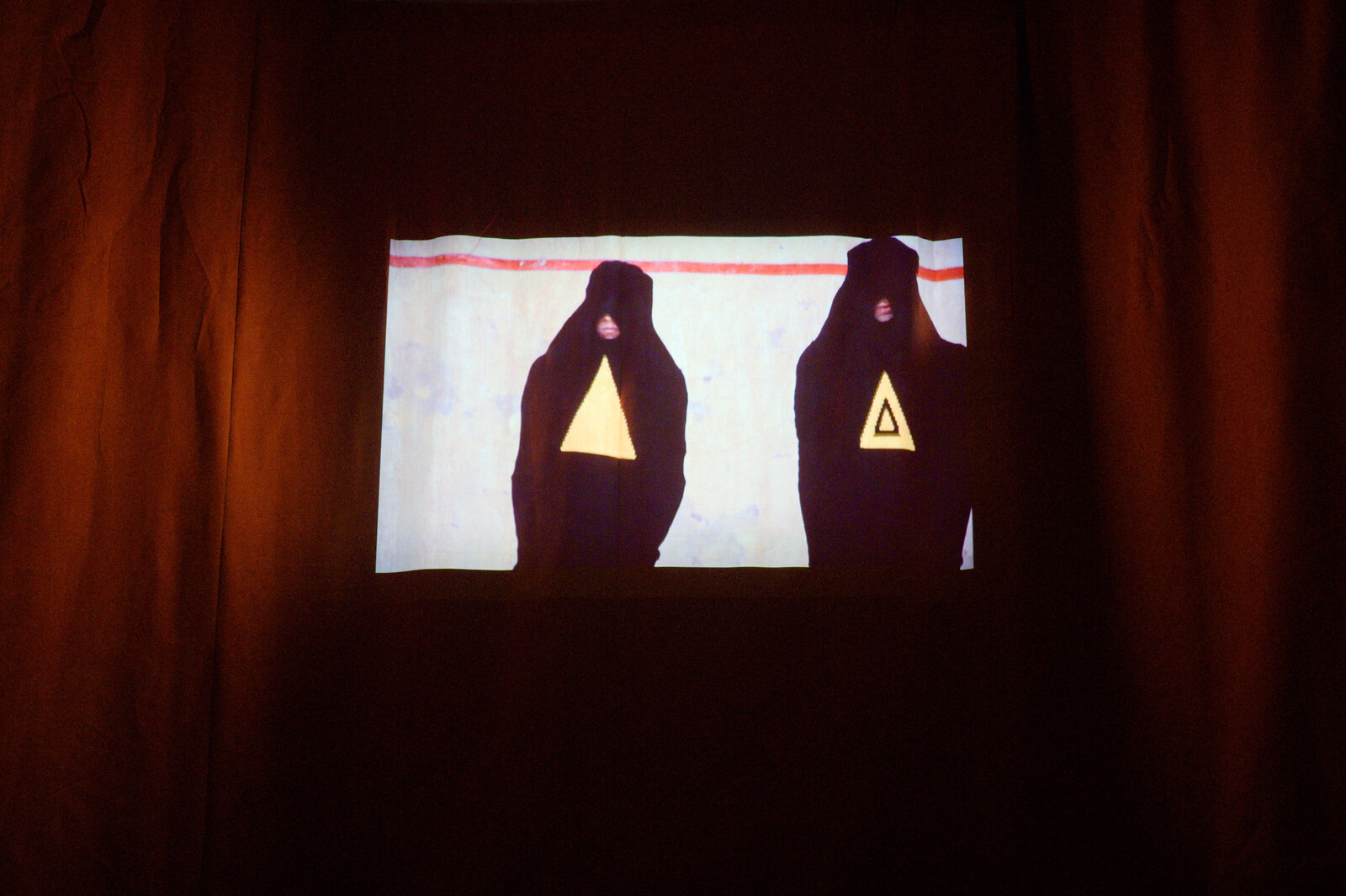

After the brief introduction, we are welcomed into a room surrounded by a soft orange curtain. The space is illuminated only by the projection of a new, 11-minute video version of one of Diaz’s performances, /A Å Æ )A(, dating from 2019. Two characters wearing black, triangular, and armless costumes whose hoods conceal the upper halves of their faces pace metronomically around a squash court’s symmetrical grid. One sports a small yellow triangle on their front and a large red one on the back; the other has a large yellow and large blue triangle on front and back, respectively. The triangular symbols, hooded faces, and mechanical choreography create the sense of a sinister exercise unfolding. Until, that is, the two characters collide and howl. At this point, the guide takes us to the next room, empty but for three long sheets of paper mounted on a corner. A strobe light makes it difficult to see them, yet the last scroll contains a “score”: a pattern of graphic shapes, drawn with a typewriter, corresponding to the performers’ actions. After a few visually uncertain moments, the guide directs us into the third room.

A large black knitted blanket hangs from a branch across the middle of the space. A performer stands to the left of it, holding a needle and nylon thread; behind the blanket, two figures can be seen, visible from the thigh down. A gloved black hand emerges to one side. A mouth appears in a hole in the blanket, perhaps in reference to Samuel Beckett’s Not I (1972), with a life-sized ceramic pink tongue in it. The hand grabs the tongue from the mouth and delivers it to the performer closest to the audience, who threads it onto a string. As the cycle repeats, a giant necklace of intermittent tongues separated by copper piping begins to form. The whole enterprise is monotonous, tense, and tinged by dread—and, perhaps, a sense that things are dragging on for a touch too long.

While it brings modernist theatrical traditions to mind, Diaz’s work feels more closely related to another Argentinian’s. Marina De Caro also weaves sound and performance worlds out of knitting, language, and the potential of the humble line. But while De Caro’s creations are expansive and baroque—and closer to Argentina’s political and pedagogical art traditions—Diaz’s worlds are simple, binary, self-contained. More than worlds, they are autonomous mechanisms. But, as with any system, even the simplest of tasks can go awry. In the translation of score into action the unexpected, the absurd, and the funny have a way of slipping through the cracks. Once the giant necklace of tongues is complete, the mouth disappears from its hole. The performer hangs it on the wall behind the blanket. As we are about to leave, there is a loud crash. Pink shards cover the floor. “Oh no!” we gasp. “Was that intentional?” Our guide simply shrugs with a smile.