When the clock struck twelve in Berlin, “in search of characters…” transitioned from Galerie Neu’s final offering of 2017 into its first of the new year. Twenty-two works by fourteen artists comprise the exhibition exploring “questions of artistic identity/ies, authorship, and authority,” per the gallery press release. These perennial investigations take on various forms, but whether a painting or a minibar, all are aerated by two mischievous thoughts.

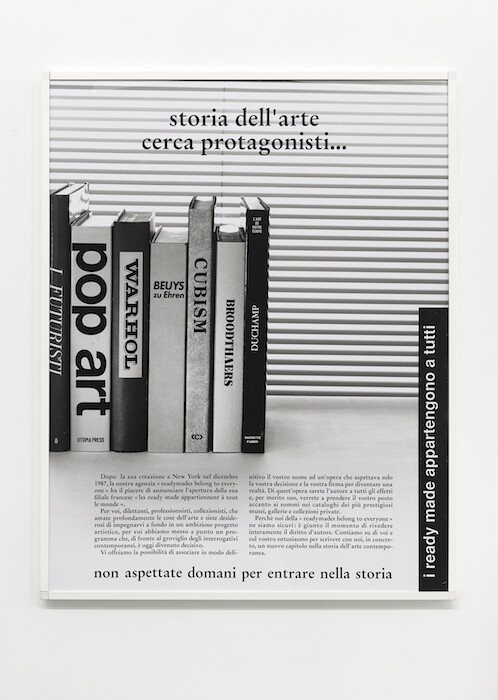

The gallery text conveniently articulates one: a rendition of the Duchampian “readymade” concept that, in 1914, crumbled the menhir of originality into the gravel upon which conceptualism has been driving in donuts ever since. At Galerie Neu, the most obvious benefactor of this tradition is Pubblicitá, pubblicitá, a 1988 advertisement designed for Philippe Thomas’s elusive faux company called “readymades belong to everyone ®.” Appearing as a poster and a postcard, it promotes the company’s initiative for a “total revision of authorial rights,” providing on-demand readymades ripe for inclusion among “all the best museums, galleries, and private collections.” Once in hand, the readymade product is in the custody of the buyer, who becomes its “sole and absolute author” (and art history’s exclusive canon becomes oversaturated with consumer anarchists). Sujet à discrétion (Subject to discretion) (1985), also both by and not by Philippe Thomas, more intricately demonstrates “his” riddle. Three identical color photographs of the Mediterranean are paired with wall labels including convoluted metadata. One is listed as a generic multiple by an anonymous maker, another is cited as a poetic self portrait of Thomas (also a multiple), and a third is a unique self portrait of readymades belong to everyone ® customer Bruno Hoang. The installation plays a shell game, enticing us to keep an eye on the marble of integrity amid shuffling attributions. In actuality, the marble is nowhere to be found, for it has been swallowed up in its very own sea.

So much trickery elicits a sinking feeling despite the overwrought and familiar postmodernism. One might think, given the post-truth tenor of current affairs, we would be desensitized to such intellectual booby traps, but thankfully, blessedly, something as understated as a fishy wall label still has the capacity to hit a nerve. We are not gullible, but we are delicate. The realization that nothing is stable will always be troubling, no matter how often repeated.

“in search of characters…” challenges our dependence on the proverbial wall label, suggesting that when it is invalidated, when it is peeled away completely, we are inadequately prepared for the outcome. Detrimentally, we fail to recognize an open-source creative nirvana beyond cultish art-world stardom but instead perceive ourselves lost in a desolate wasteland without markers. This is the second mischievous thought, and it tempers the holier-than-thou readymade.

Non-attribution’s dark side has a destructive, noir flavor. Take, for example, Alex Hubbard’s Untitled (2017), a miniature liquor cabinet backed with mirrored glass. Set at standard shoulder height, it provides an isolated drinking experience for the person standing before it, who is invited to watch his or her composure melt away with each successive shot consumed.

On an adjacent wall, Emily Sundblad’s 2017 watercolor-and-pencil drawings on stationery from Ett Hem, a premier boutique hotel in Stockholm, depict frenzied marks that occasionally coagulate into a recognizable subject. A distorted face appears in one, its countenance implying a dire scenario filled with delirious substance abuse in nightly-rented rooms à la The Lost Weekend (1945). The alcoholic rapport between Hubbard and Sundblad recalibrates the lens through which the others are considered.

Kirsten Pieroth, in particular, has a knack for the grim. Her works Abrasives (2017) and Monolith (2014/2017) both evoke anonymous car violence. The former, a catalog of scuff, tread, and impact marks pounded onto newsprint pages from the Frankfurter Allgemeine, resemble hit-and-run tire skids. The latter seems to have once been a sink but is now crushed into a metal lozenge. Although diminutive, its shape and luster mimic a compacted junkyard vehicle, likely after being totalled on the highway. Thanks to some curatorial acumen, Monolith’s solemnity is enhanced by its close proximity to Klara Lidén’s fiendishly redacted road sign, Untitled (2016), which is missing all vital, life-preserving information—another booby trap positioned to send us off the cliffside into an illusion of the Mediterranean Sea.

To come to such an end might not be so bad. Perhaps it is there, on the ocean floor, where we find the tranquility missing from non-attribution, or where we go to recover the marble of integrity and with it dissolve into sand.