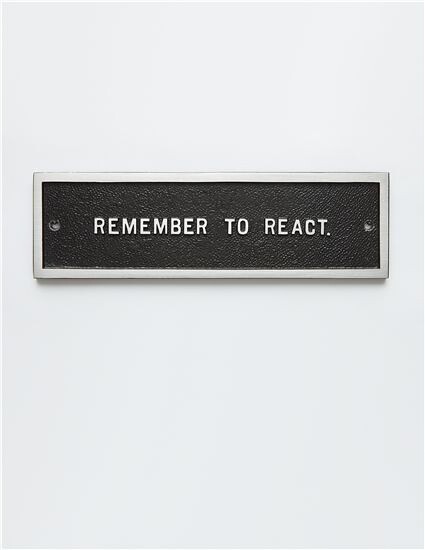

Remember to React. Jenny Holzer is trying to tell us something. She has been trying to tell us something since the early 1980s, when she conceived her “Survival” series, from which that sentence emerged. If you’re looking closely, it’s one of the first things you’ll see at Art Basel Miami Beach (on a small plaque inside the booth of Sprüth Magers, Berlin). Like many great artists from her generation, she was reacting to an especially volatile sociopolitical climate and this provocation was a pointed reminder of the necessity to fight apathy in outrageous times. It’s also a reminder that many of the galleries within the fair seem to have missed.

Last year, there were only a few short weeks between the American election and Art Basel Miami Beach’s schedule of events, and only a few artists and gallerists were able to properly respond to what had transpired: Jonathan Horowitz’s edited photograph Does she have a good body? No. Does she have a fat ass? Absolutely (2016) showed Donald Trump shooting golf balls into flame-colored skies; Rirkrit Tiravanija painted the phrase “The Tyranny of Common Sense Has Reached Its Final Stage” on November 9 editions of the New York Times; Blum & Poe placed Sam Durant’s End White Supremacy (2008) on the wall facing one of the main entrances, forcing visitors to confront it as they walked in the fair.

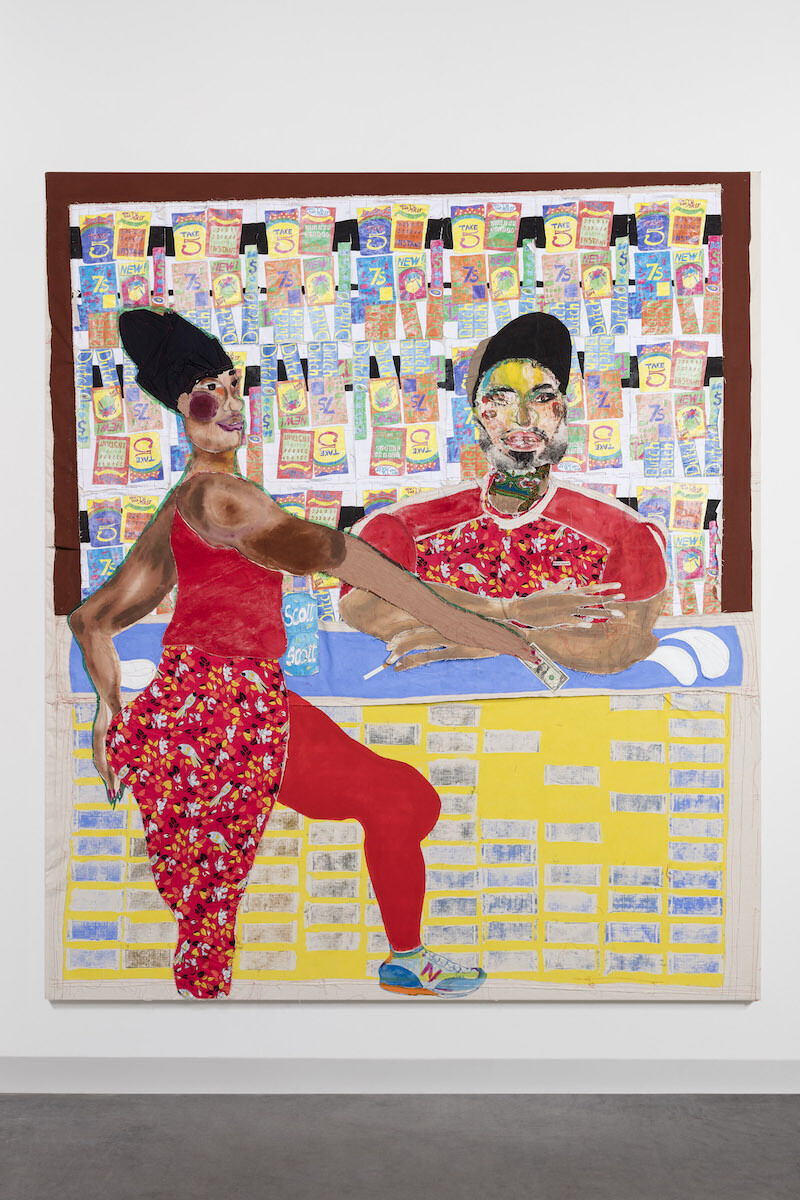

Lazy and Stupid. Maybe Christopher Wool was trying to tell us something too. After wandering the fair for several hours, I came across a text painting on aluminum that includes that phrase in the booth of London’s Simon Lee Gallery and thought it summed up my feelings about the majority of the stands in this year’s edition. Perhaps I was naïve in thinking that the galleries in the fair would be responding to recent events. In some ways, they have, by noticeably raising their inclusion of women and people of color, but that market correction has been a long time coming; it’s refreshing to see artists like Lee Krasner (who has a sensational large-scale work, 1957’s Sun Woman 1, at New York’s Paul Kasmin) in the blue-chip big leagues and young stars like Tschabalala Self (with a small but lively selection of paintings and sculptures at London’s Pilar Corrias) gaining market success and notoriety. But by and large, Art Basel has increasingly become an echo chamber, failing to challenge its audience in any meaningful way.

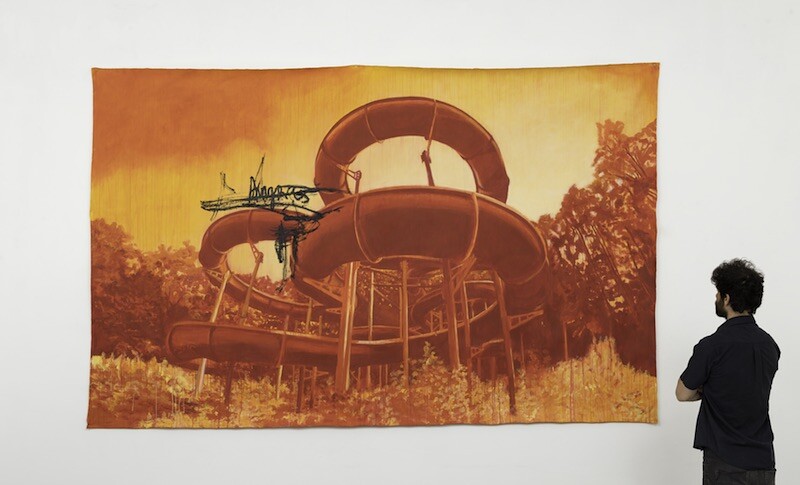

While many galleries failed to react, there were a few surprises to be found throughout. Continuing her investigation of human-made catastrophes, Dora Longo Bahia presents two paintings from her series “Nuclear Accidents” (2017) at Vermelho, São Paulo; the works depict abandoned theme parks after the fallout of two of the most famous nuclear disasters, Fukushima and Chernobyl. The contradictions between recreation and devastation are unsettling, and I couldn’t help myself from being reminded of the orangey post-human wasteland of Blade Runner: 2049 (2017), which portrays most of civilization living off-world, with biorobotic androids making up most of the narrative.

It’s easy to love Peter Saul, who has one of his signature surreal and kitschy political caricatures of Trump up at New York’s Mary Boone Gallery (this body of work draws parallels to Philip Guston’s satirical Nixon drawings from the 1970s). This time, Saul dresses Trump in Wonder Woman drag as he fights Kim Jong-un in a feverish battle involving nuclear warheads (President Trump Becomes a Wonder Woman, Unifies the Country and Fights Rocket Man, 2017); as with most of Saul’s oeuvre, the work is funny, frenetic, and also a little terrifying. But I may prefer Filipino painter Manuel Ocampo’s visceral canvases at Tyler Rollins Fine Art, New York, where a series of gut-punching, gonzo works borrow imagery from political cartoons from the Philippine–American War, among other sources, to explore America’s history of colonialism in his homeland. The paintings are wretched, vile, and ferocious, and populated with horrendous creatures, historical racial caricatures, and cartoonish figures.

At New York’s Maccarone, Nate Lowman fills a massive wall with three large-scale paintings utilizing appropriated radar images from 2017’s major hurricanes: Harvey, Irma, and Maria (all 2017). Hung as a trio, the arrangement recalls a scene from the early aughts climate-change disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow (2004), which shows a fictional radar image of three major tropical storms raging across the globe, a fiction that became a reality this past September.1 Lowman had already created hurricane radar paintings once before with Hurricane Katrina, and with climate change expected to accelerate the frequency and intensity of tropical storms, he has created perhaps his most cynical body of work yet.

But my favorite booth by far was in Art Basel’s Survey section, which is dedicated to historical projects (and overall is quite excellent). São Paulo’s Galeria Jaqueline Martins dedicated its booth to the late Brazilian artist Letícia Parente (1930-1991), who created a deeply experimental oeuvre that explores the body and the domestic space. The gallery notes that Parente dedicated her practice to “denaturalizing the body, considering the body as something that is produced by biopolitical forces.” This is most evident in the video works presented in the booth. In one video, In (1975), she hangs herself in a closet as she would any other garment, shutting the door on herself and shutting out the world with it. In another video, Tarefa I [Task I] (1982), a maid irons the artist’s garments as she wears them while laying on an ironing board, with no sense of struggle or pain. The most wrenching is Marca Registrada [Trademark] (1975), which depicts the artist sewing the words “Made In Brasil” on the soles of her feet, highlighting the body’s relationship to its motherland. While she keeps a straight face, there is a palpable sense of the anger and rage that lies deep beneath the surface. With her reactionless actions, she has perhaps created the most potent reaction of all in this year’s fair.

I couldn’t help but be reminded of the curators of this year’s Whitney Biennial telling the New York Times earlier this year that they decided to make no changes to the show after Trump’s election, and 57th Venice Biennale curator Christine Marcel deciding to focus on the artist and art practice in a post-Brexit Europe with nationalism on the rise.2 For the most part, it seems that most of the galleries in this year’s Art Basel have looked out at the world and decided to sit on their hands, resulting in a fair that it is the same as it ever was: overblown, decadent, and largely oblivious to the world outside the convention center. In some ways, this is to be expected, but that doesn’t make this any less depressing. There is always a risk in choosing to respond to the times, but the rewards can often be like Letícia Parente’s work: urgent, cathartic, and vital.

http://edition.cnn.com/2017/09/06/americas/three-hurricanes-atlantic-basin/index.html.

Jason Farago, “A User’s Guide to the Whitney Biennial,” New York Times (March 8, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/08/arts/design/a-users-guide-to-the-whitney-biennial.html.