March 8–May 15, 2017

“I don’t know what it’s like to be black in America,”1 wrote the artist Dana Schutz in her protracted defense against calls for the removal and destruction of her painting Open Casket (2016). She was responding to mounting fervor over her rendition, included in the Whitney Biennial, of the mangled face of African-American teen Emmett Till, savagely murdered in 1955 at the hands of white racists in Mississippi. Arguments on both sides of the divide hovered around the impossible “knowability” of the “other,” with Schutz (clumsily) claiming art as a space of empathy, and her detractors foregrounding the artist’s blithe appropriation of a charged episode in American visual politics, resulting in the trivialization of black suffering. As the debates raged on, this thorny question of knowing the other quietly surfaced in French-Moroccan artist Mounir Fatmi’s show “Inside the Fire Circle” at Lawrie Shabibi in Dubai.

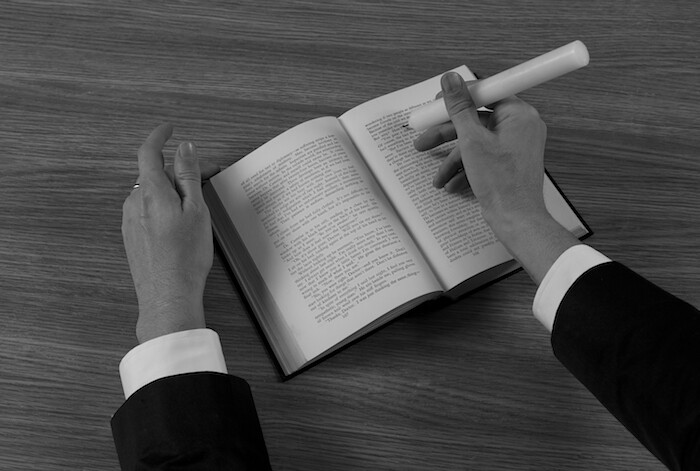

Continuing his fascination with the archive (a mainstay of which is the cogent 2006-2009 project “Out of History” examining the Black Panthers Party), Fatmi has unearthed a moment in late 1950s American race-relations history through the exploits of Texan journalist John Howard Griffin (1920–80). Determined to “experience discrimination” as did a black man in the harshly segregated Deep South of the time, Griffin deliberately darkened his skin by downing pigmentation pills, soaking up UV rays, and applying a skin stain. The perpetual high-school-reading-list fixture Black Like Me (1961) is the literary fruit of his six-week peregrination, his personal crusade to rile America into opening its eyes.

For an artist whose emblematic figure might be the circle—the circular saw blades emblazoned with Koranic writings that featured in his installation Interventions (2010), the Duchamp-inspired rotoreliefs of Technologia (2010), the looping nature of his oft-used VHS tapes and jumper cables—linearity permeates Fatmi’s works on Griffin. As A Black Man (2013-14) is a lineup of ten photographs that capture Griffin’s white-to-black metamorphosis: the first headshot of Griffin with his natural pigmentation and the last showing his blackened skin are both archival; the others are darkening grayscale manipulations of the first. Before-and-after state change crops up in Darkening Process (2014), a single-channel video composed of color-filtered outtakes from the hokey 1964 film-of-the-book Black Like Me, interspersed with black-and-white shoe polishing sequences: tightly shot white hands become blacker as the polish rubs off, and the ebony paste is sometimes directly applied to the skin.

Two nearby photos—Crossing the Line 01 and 02 (both 2015)—insist yet again on a rather flat from/to transformation: the images of a man’s feet hopping across a traffic line recall the heavy-handed moments in the film when Griffin first “accesses” life among the segregated, then crosses back to his existence as a white man. The show’s remaining images featuring Griffin are all manipulated archival photos—juxtaposed, overexposed, and repeated. The Interview (2017) is a twin shot of Griffin in an uneasy-looking interview with famous news broadcaster Mike Wallace. The upper image of the pair is overexposed, as if seared or burnt. Similarly, The Mirror (2017) is a manipulated shot of Griffin’s first look at his skin change—the image somehow throbs.

Fatmi’s hallmark strategy is to cultivate suspense—setting up a tension, bringing discomfort to the surface—by hinting at some deeply charged critique, but ultimately leaving the problematized situation unresolved. At worst, it can come across as “one-liner” art; at best, it makes for compellingly uncomfortable viewing.

Yet “Inside the Fire Circle” pales in relation to the tension of his best efforts. The work, specifically the pieces on Griffin, flattens the depth of identity by a process-driven, over-literal insistence on this-to-that transformation. The potential uneasiness of the show—staged in the Middle East, where identity is always layered—is deadened by mere photographic sleight of hand, ignoring some of the issues that Griffin’s legacy raises: with what authority does Griffin speak to Mike Wallace on behalf of all black people? And what of the fundamentally perverse gesture of treating race as malleable, to be dipped into for a privileged man to make a point? Is this “experimental otherness” any less blithe than Dana Schutz’s appropriation of the visual rhetoric of Till’s open casket?

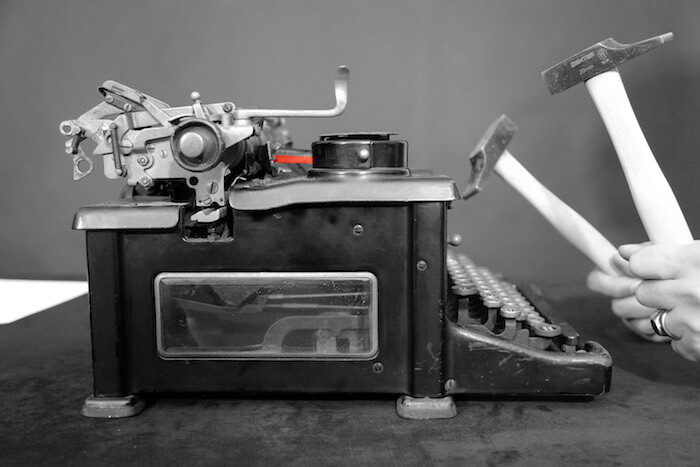

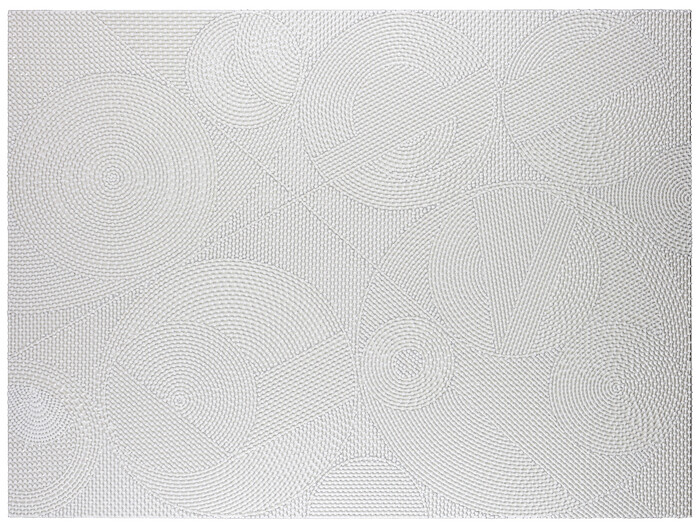

While the show succeeds in sidestepping a region-pleasing, best-of approach to Fatmi’s work (notably anything with Koranic texts), it also seems to have backed itself into an anecdotal take on a single figure, meaning the stronger works take an undeserved backseat to Griffin’s transformation. Both Inside the Fire Circle (2017)—a bank of vintage typewriters linked up to jumper cables connected to pristine sheets of white A4 paper languishing on the floor—and Kissing Circles 09 (2010-11)—Fatmi’s tried-and-true all-white coaxial antenna cables, painstakingly snipped and set in a static ballet of cog-like circles—level far more impact while dealing with the archive, obsolescence, language, and our unwritten future.

It is precisely Fatmi’s sensitivity to language that is lacking from the Griffin works. Since Griffin himself was exiled from the language of the other (“Teach me how to speak,” he implores the black shoeshine worker he takes into his confidence in Black Like Me), he was reduced to a surface, a skin color. Perhaps Fatmi’s insistence on the purely visual result of his metamorphosis drives this point home. But ultimately the works lack the ballast that would endow them with the necessary tension. For now, like shoe polish—as loaded as it may be with ironic tones of instrumentalized racial transformation—they just fade away, without further consequence.

Dana Schutz’s statement to the press on March 21, 2017: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/arts/design/painting-of-emmett-till-at-whitney-biennial-draws-protests.html?_r=0.