In the totalitarian America of Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953), books are outlawed and routinely burned. Resisting the destruction of literature and defending the existence of dissenting ideas, characters in the novel return to oral traditions and learn books by heart. Mette Edvardsen’s project Time Has Fallen Asleep in the Afternoon Sunshine (2010–ongoing) transforms Bradbury’s idea into action. Since 2010, she has accumulated 80 living books—human performers who enact pieces of literature. The work is typical of the artist’s choreographic oeuvre, which often includes minimal gestures, mundane objects, and language. While such approaches are common to contemporary choreography, Edvardsen’s piece questions these tools and their impact on the choreographic turn in contemporary art.

A selection of these living books is present at Index Foundation in Stockholm alongside the original novels, which are displayed on white shelves. There is also a “shadow library”: a collection of printed books that might come alive, or were about to, but have not yet. I choose a title from the list of living books. A few minutes later, I’m approached by one of the performers. “Hello, I’m In the Skin of a Lion by Michael Ondaatje,” she says, and asks me to follow her to a corner by the front window, where we stand still. The book tells me her story about immigrant workers in 1930s Toronto from the beginning, until…I don’t know how far she gets through the story. Without further notice, the book says “thank you” and “goodbye.” I’m left in the mixture of imagined scenarios from listening, and the view of the snowy yard outside.

Time Has Fallen Asleep in the Afternoon Sunshine is not a performance about literature, but the practice of memorization. Yvonne Rainer formulated a similar idea in a 1965 essay “The Mind is a Muscle,” stating that her body “remains the enduring reality.”1 She was at that time still actively dancing, reconfiguring the present through recurring, ever-changing movements that she “found,” in a Duchampian manner, in everyday life. In Time Has Fallen Asleep, the listener’s attention is as important as the performer’s presence: the present of the live performance must be understood in plural, as a matter of collective action. Beyond a singular and subjective moment, an assembly of lived-through “nows” enact the liveness of the artwork.

In their 2017 book Now, The Invisible Committee argue that both the past and the future must be understood through their “now”: instead of relying on the mediation of historical explanations, they call for “a frank relation to what is there”—truth that doesn’t accumulate through commentary but “manifests itself in a situation and from moment to moment.”2 Although the authors refer to direct political action, their words might equally apply to the “now” of performance. Surpassing contemporary art’s quest for attention, Time Has Fallen Asleep performs an ethics of time, making duration its central medium. In between the living book and the living listener, a grammatical détournement is achieved, one that constitutes the lasting publicness of the performance. And although performance is inherently public, these ethics enable its very emergence.

Enacting multiple “nows” in a myriad of places (Time Has Fallen Asleep has been performed in multiple international venues) Edvardsen’s performance enables a publicness that wouldn’t exist outside itself. This heterotopic praxis creates what researcher Adam Czirak termed the “second public sphere”3—temporary situations and places emerging from social and artistic interaction. The notion was initially developed as part of Czirak’s research on performance in countries with limited access to the public sphere, the kind of regimes Bradbury’s fiction satirizes. In such a context, Edvardsen’s piece is a practice of aesthetic autonomy beyond a contemporary market of affect and sociability; not a temporary autonomous zone, but rather a commons of the here and now.

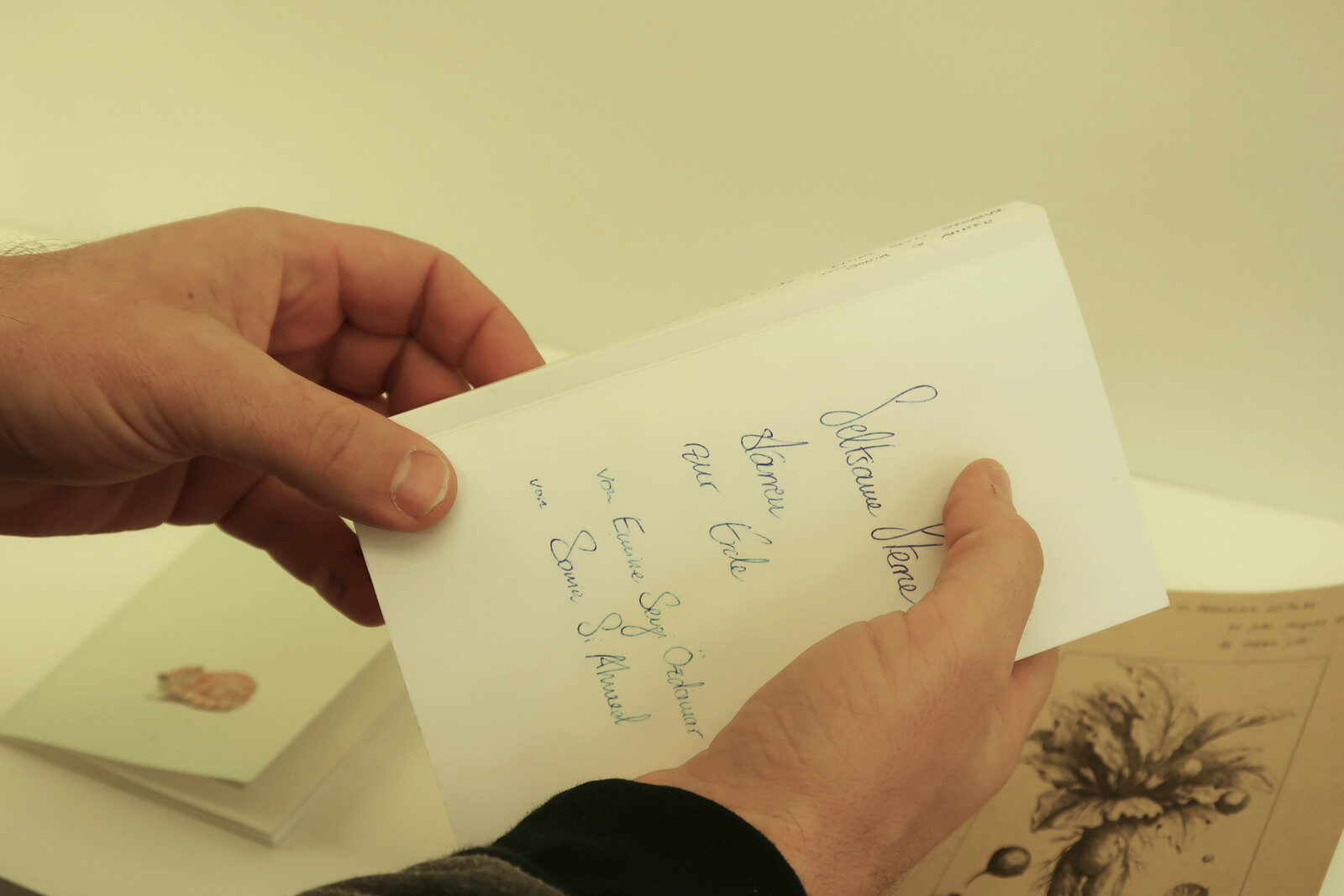

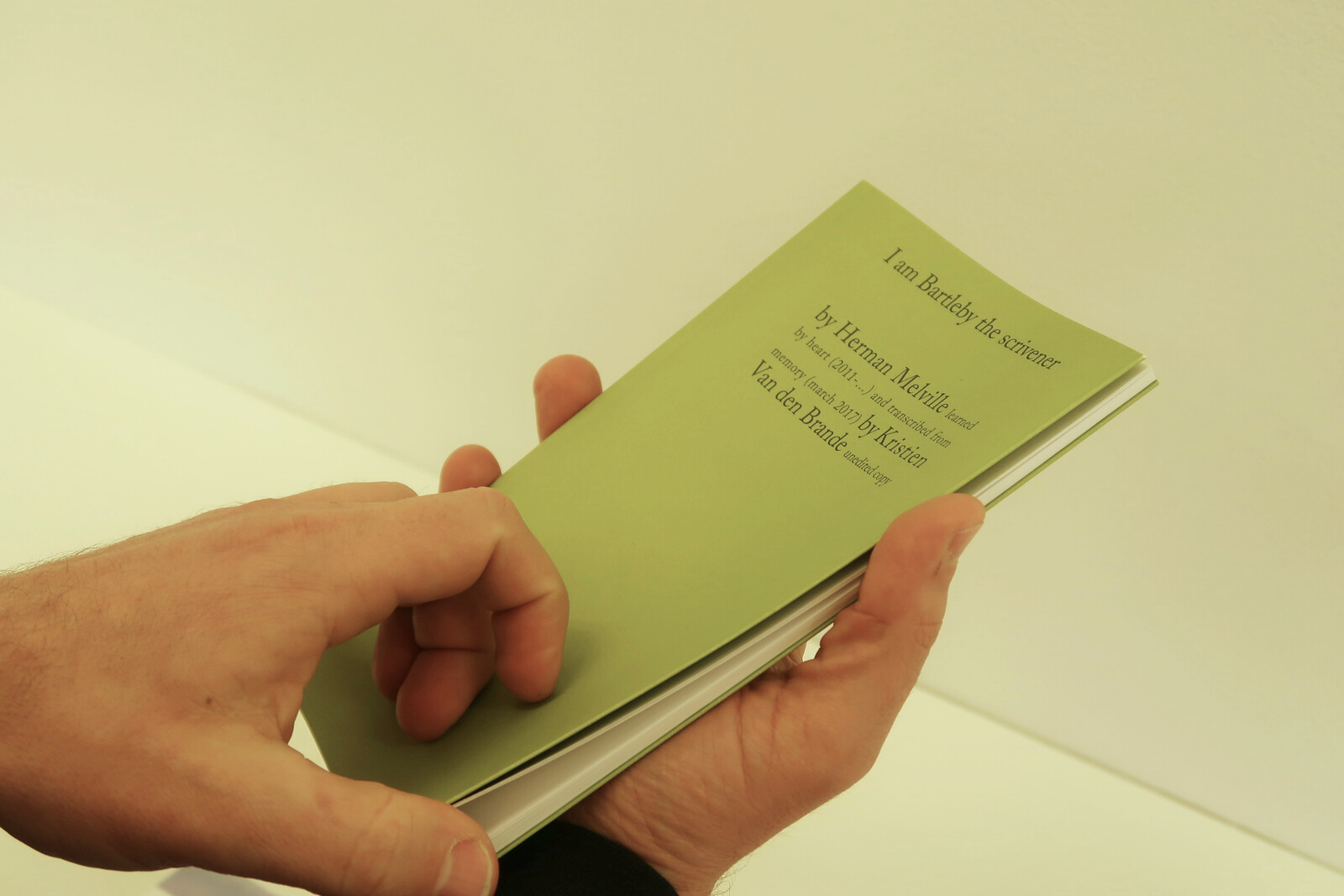

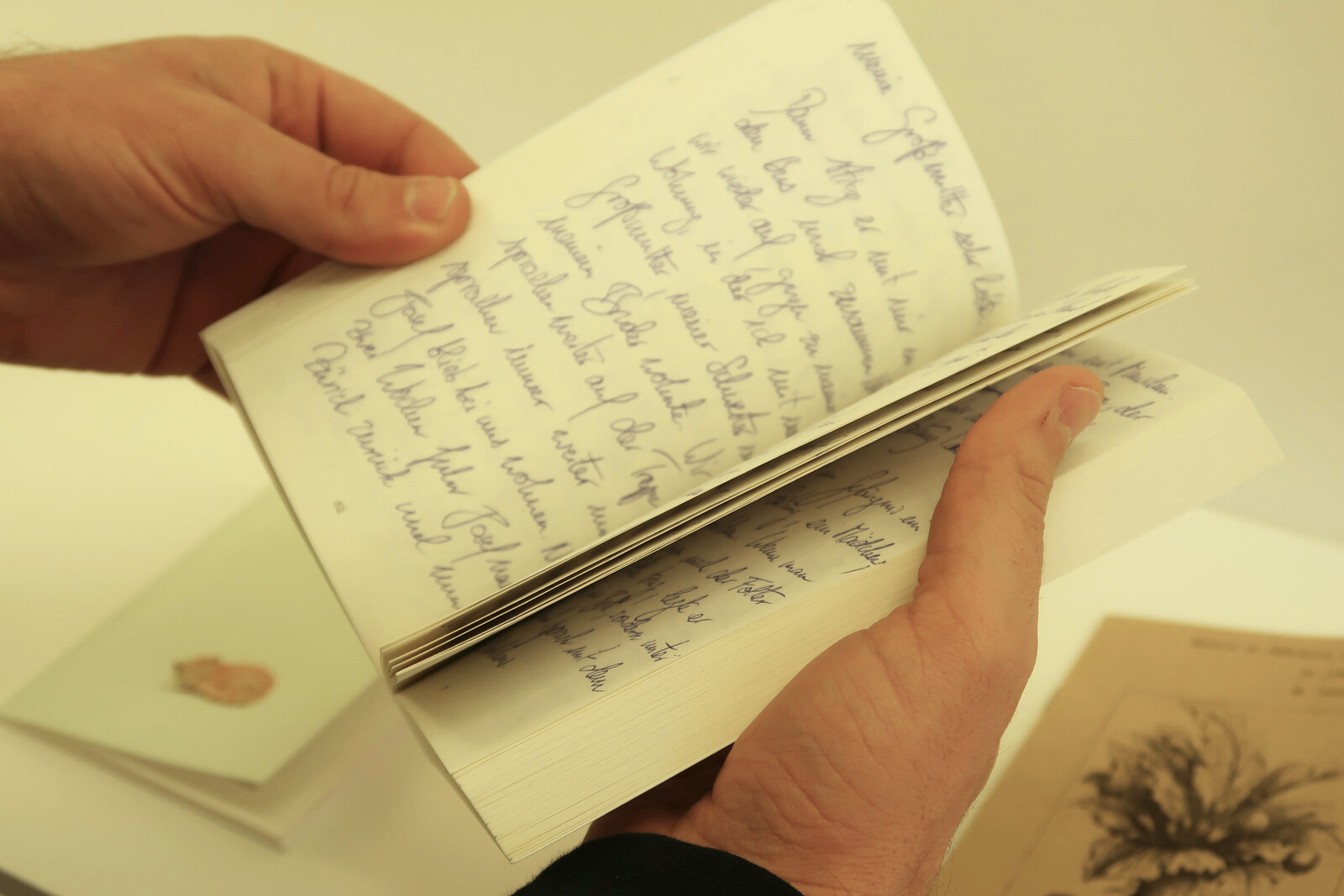

In recent years, her living books have been written down from memory and published as alterations of the originals. At Index Foundation, I find Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street and compare it to Herman Melville’s 1853 original on a neighboring shelf. The differences are as subtle as Rainer’s choreographic adaptions of social life. I realize that it’s me, the reader, who is the missing part between the two texts. It is my responsibility to enable the work’s public emergence in the enduring reality of a present—a present that Edvardsen succeeds in redistributing to, and together with, the many.

Yvonne Rainer, “The Mind is a Muscle” in Tulane Drama Review Vol. 10, issue 2 (Winter, 1965): 178.

Invisible Committee, Now (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2017), 10–12.

Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak (eds.), Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-based Art in Late Socialist Europe (New York: Routledge, 2018).