Occupying a pocket of undeveloped land in Long Island City, “The World’s UnFair” is a principled riot. Created by New Red Order (NRO), a “public secret society” facilitated by artists Jackson Polys, Zack Khalil, and Adam Khalil, this carnivalesque fairground, supported by Creative Time, is presided over by Ash and Bruno, a sixteen-foot animatronic tree with LED screens nestled in cellular tower branches and a furry five-foot tall beaver, respectively. The pair talk about the legacies of settler colonialism on the land where they stand, Lenapehoking—a forest, they say, the last time they met. America’s original multi-millionaire John Astor is mentioned: he made his fortune in the fur trade that all but decimated beaver populations, before acquiring land in Manahatta and making “a killing off renting to incoming settlers.”

The politics of land is at the heart of this roadshow. Staked into the earth is New Red Right to Return (2023), a wooden post with directional markers naming Lenape diasporic nations displaced by settlers due to the fundamental difference between the colonial European treatment of land as a commodity and the Indigenous American understanding of it as a communal resource. That discrepancy complicates the narrative that the Lenape sold Manahatta to the Dutch in the 1600s—an event that Lenape communities have explained was perceived as an agreement to cohabit, rather than a relinquishing of territorial rights. Nearby, flags representing tribes within the United States border Fort Freedumb (2023), a white picket fortification enclosing a white cheval-de-frise supporting a screen playing Give It Back: Stage Theory (2023). Acid-toned digital edits of John Egan’s motion painting Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley (c. 1850) are edited into an infomercial introducing a key NRO slogan: “Give it Back.” The phrase refers to the Land Back Movement for the restoration of Indigenous land stewardship and sovereignty, and appears on posters wheat-pasted to a street-facing wall alongside phrases like “Promote Indigenous futures.”

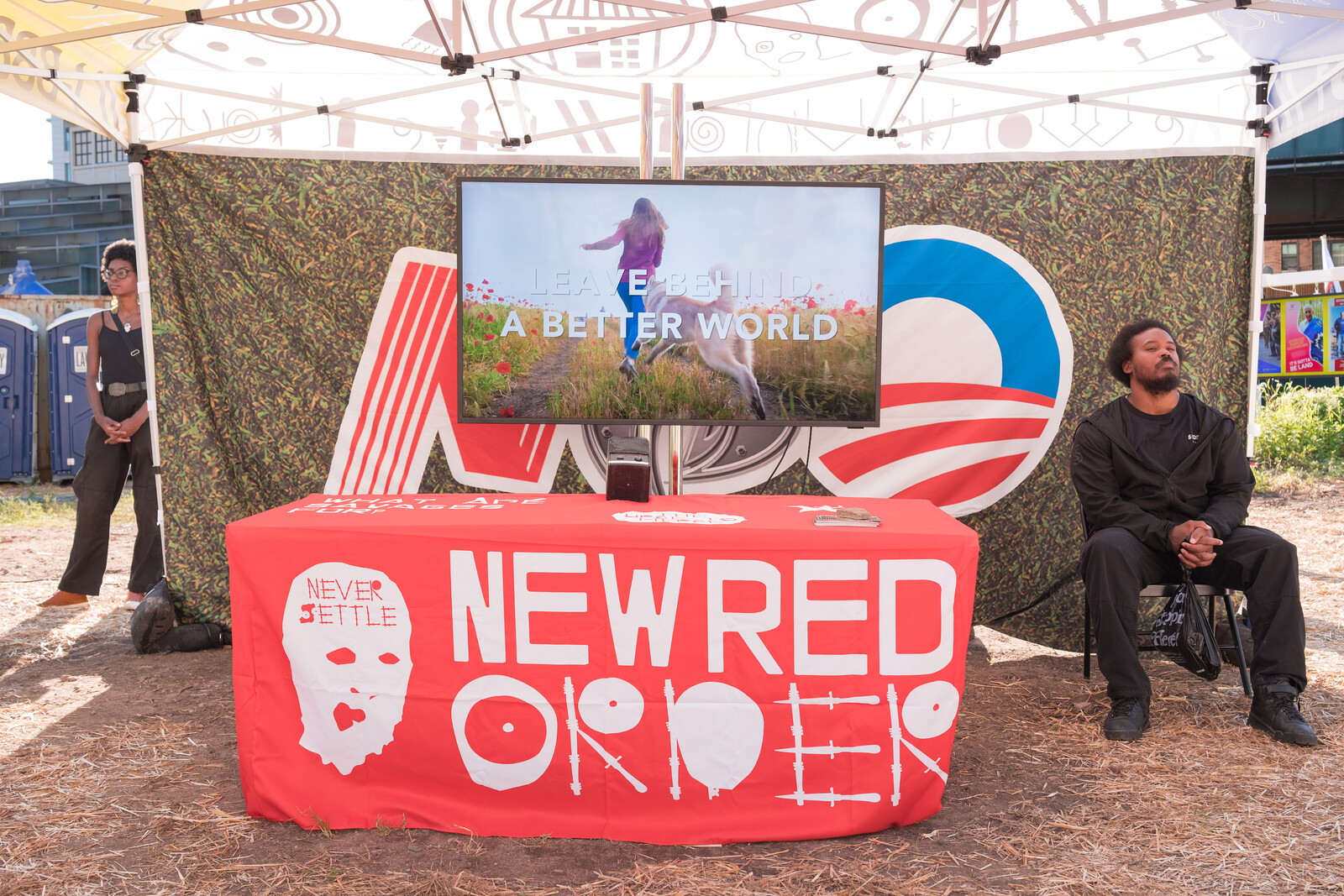

Recruiting people into a Land Back state of mind drives the NRO project. Appearing across video works is white actor Jim Fletcher, who joined the “NRO Informant Pilot Program” after being called out for impersonating a Native American in a theater play. In Never Settle: Calling In (2018), a video playing under a recruitment canopy as part of the installation Conscientious Conscripture (Pow Wow Edition) (2018–ongoing), he performs the role of spokesperson. Mirroring the tone of a wellness-focused ad campaign, Fletcher extends the sentiments of Give It Back: Stage Theory, where Land Back is presented as a solution to the apocalyptic crises plaguing the present—an experience of catastrophic annihilation that befell Indigenous communities long ago. “Be a part of the solution, leave behind a better world, never settle,” he says, introducing NRO as an agency facilitating feel-good decolonial action.

Resisting a collapse into irony, a video screened inside a shipping container showcases one example of Land Back, as part of Give it Back: Crimes Against Realty (2023), a series of four installations dispersed across the site. Speakers including Lulani Arquette, president of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation (NACF), introduce the transfer of the Oregon-based non-profit arts space Yale Union’s building and land to the NACF in 2020: an act not of “repatriation” but rematriation, Arquette notes, redefining return as a process of rebirth. Lining the walls are framed real estate listings, each introducing an instance where Indigenous land has been returned. Among them is Tuluwat Island, stolen from the Wiyot in 1860—the year white settlers massacred them during a ceremony for world renewal—by the Californian city of Eureka in 2019. The return of Tuluwat Island is the first known voluntary municipal land return in the United States. After decades of advocacy, the Wiyot raised the funds to acquire 1.5 acres of the roughly 250-acre site in 2001, before the city transferred 45 acres to them in 2004. The Wiyot proceeded to nurse the land to health after its contamination by a shipyard established there not long after the 1860 massacre, demonstrating how, as Fletcher notes in Give it Back: Stage Theory, collective action can lead to concrete change, and Indigenous knowledge can respond to ecological catastrophe.

But obstacles to forging such healing paths remain. Screened from a real-estate signpost, one video shows the governments of Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, plus the British Crown, officially apologizing to Indigenous peoples for the injustices inflicted upon them—gestures that too often remain platitudinous, as demonstrated by a recent referendum in Australia, which crushingly rejected a proposal to enshrine an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice in the constitution. Fletcher roleplays the mentality blocking such resolutions, with phrases like “It’s not our fault” highlighting an insidious deferral of responsibility, also evoked in a therapy session he performs in another video. “They’re asking me to give up control,” Fletcher says—a prospect which has driven settler-colonial powers to acts of unspeakable violence. Once the myth of entitlement to stolen lands is given up, the gap between rhetoric and action might finally close.