From the colonial origins of modern science up to today’s decolonial reckoning, art’s relationship with botany has been complex and contested. Since the seventeenth century, botany has played a vital role in how we understand, attend to, and live within the world of plants. But as an instrumental science it is obsessed with order, naming, and hierarchy on the basis of contested criteria. In the colonial era, botanists undertook military missions, served on slave ships, and displaced indigenous practices for monocrop agriculture worked by generations of enslaved people transplanted from one violently colonized land to another. London’s Kew Gardens oversaw networks of extraction (quinine, rubber, breadfruit) and supported experimental gardens across the colonies to keep the plantations profitable. However, as Jamaica Kincaid has noted, a botanic garden can be a tool and symbol of colonial oppression and, at the same time, “Edenic.”1 The botanic garden has recently been the site and subject of contemporary art exhibitions from Palermo to Berlin, addressing the entanglement of science with colonialism. So how can the practice of contemporary art assist in the process of decolonizing these “treasure houses”?2

With its origins in an era that saw violent enclosure of common land, witch trials, colonial expansionism, and trans-Atlantic slavery, the botanic garden has traditionally been constructed as a bounded space: a place of projected perfection and as a laboratory for the nascent natural sciences. Recently, attempts have been made to imagine gardens without policed borders between inside and outside: in the 1990s Gilles Clément advocated for a planetary garden, an ethics of care that informed Manifesta’s 2018 presence in the Palermo Botanic Garden; Michael Marder, a significant influence on Camden Arts Centre’s ““The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism and the Cosmic Tree” (2020), has theorized a garden without “prior circumscription” that foregoes enclosure altogether. Rather than think of the garden as a defined place, artist-gardeners such as Maria Thereza Alves (whose sound installation “You Will Go Away One Day But I Will Not” was recently shown at the Botanic Garden Berlin) or Ilya Dolgov’s focus on gardening as practice, engaging with questions of migration or challenging the artificial divisions between native and non-native. Himali Singh Soin’s project static range (2020) involves growing radiation-absorbing plants in the Indian Himalayas. Helen Walker and Harun Morrison’s Beacon Garden, Dagenham, London (2017–ongoing), flourishing on the site of a Dagenham carpark, employs slatted fencing to enable small animals to get in and out more easily.

With climate catastrophe offering the botanic garden an opportunity to reposition itself as a progressive force (as a repository for endangered plant species or a center of research for green technologies), upcoming projects like Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s pollinator commission for the Eden Project or Vaughn Bell’s “plantscapes” for Kew are being asked to serve many functions: to communicate scientific knowledge; to enrich the visitor experience and engage new audiences; to garner press coverage or look nice on Instagram. At the same time, there is a real risk that the vital work of decolonization is being outsourced to artists in a gesture towards a redistributive politics that the institution can ultimately disclaim.

It is worth noting that contemporary art is often not being funded directly by the botanic gardens themselves. At Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE), the relaunch of art gallery Inverleith House as Climate House, a three-year program conceived “to begin thinking about the role of art institutions in the age of Climate Crisis,” is supported by £150,000 from Outset Contemporary Art Fund. On the one hand, this financial independence should offer a degree of curatorial freedom. On the other hand, it means that contemporary art’s presence in the botanic garden is not deep-rooted. When the funding ends, art is easily sidelined or abandoned altogether. Edinburgh’s turbulent recent history, which saw RBGE announce the termination of contemporary art exhibitions at Inverleith House and then, following a backlash, deny having done so, suggests an institution that has struggled to comprehend the value of art.3 This may still be the case.

Climate House’s inaugural exhibition, “Florilegium: a gathering of flowers,” traversed numerous institutional faultlines with flawed but fascinating results. The ground floor was a salon-hang of botanical illustrations: tasteful but uninformative against olive-green walls. At a press preview, writer Genevieve Fay questioned the use of exclusively Latin names to accompany these illustrations. Fay’s point concerned audience accessibility, but her observation also speaks to a wider issue about botany’s relationship with language. Naming has always been an exercise in control: the bi-partite system developed by Linnaeus in Systema Naturae (1735) helped to create a community of scientists who could speak to each other across national boundaries (a potentially progressive force in an age of resurgent nationalism). At the same time, practices outside this matrix of order were violently persecuted; indigenous farming techniques and the values they embodied were often erased altogether.4

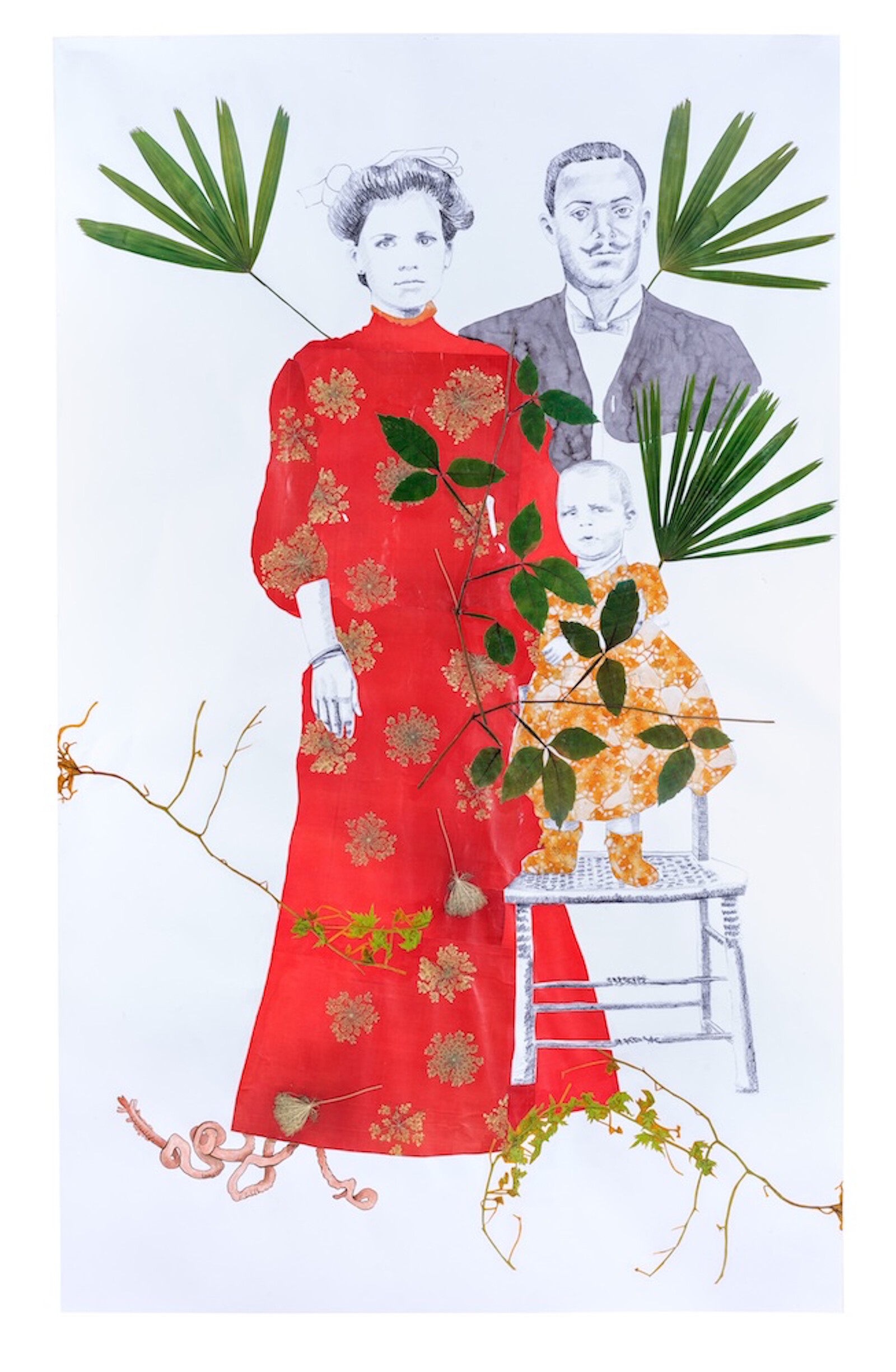

Upstairs, visitors encountered works by Wendy McMurdo, Annalee Davis, Lyndsay Mann, and Lee Mingwei. One of Davis’s series of mixed media drawings, As if the Entanglement of our Lives did not Matter (2020), depicts two figures, a man and a woman, standing together, or rather floating rootless (for they have no feet), with a baby on the chair before them. It is a portrait of a family prevented from living together by the colonial policing of relations between men and women of different races. Behind each figure springs a green fan of sugarcane. Across them trail roots and tendrils—not the fixed genealogy of the family tree, but a frayed connection teased out from oral histories and family archives. Drawn from photographs, these three faces remain grey amid floral patterns, flattened by time. In the gallery, a portrait of a plantation owner was hung adjacent.

Davis lives on a Barbados dairy farm, a site previously run as a sugarcane plantation, and her work engages with the residues of colonial extraction. Drawings in the same series show healing plants like vervain or common sow thistle alongside pink parasitic worms. They point to colonialism as monoculture, as parasite, and to the allocated plots of enslaved people as places to keep connected practices alive. Each is painted over paper from ledger books found on the plantation site. There is a brutality to these yellowing pages, where the lives of countless people are reduced to columns: day; task; total wages; stoppages; net wages. Davis’s interventions are expressive acts of reclamation. Each speaks to the enduring resistance of enslaved people and the possibility of complexity within and against the colonial drive for purity.

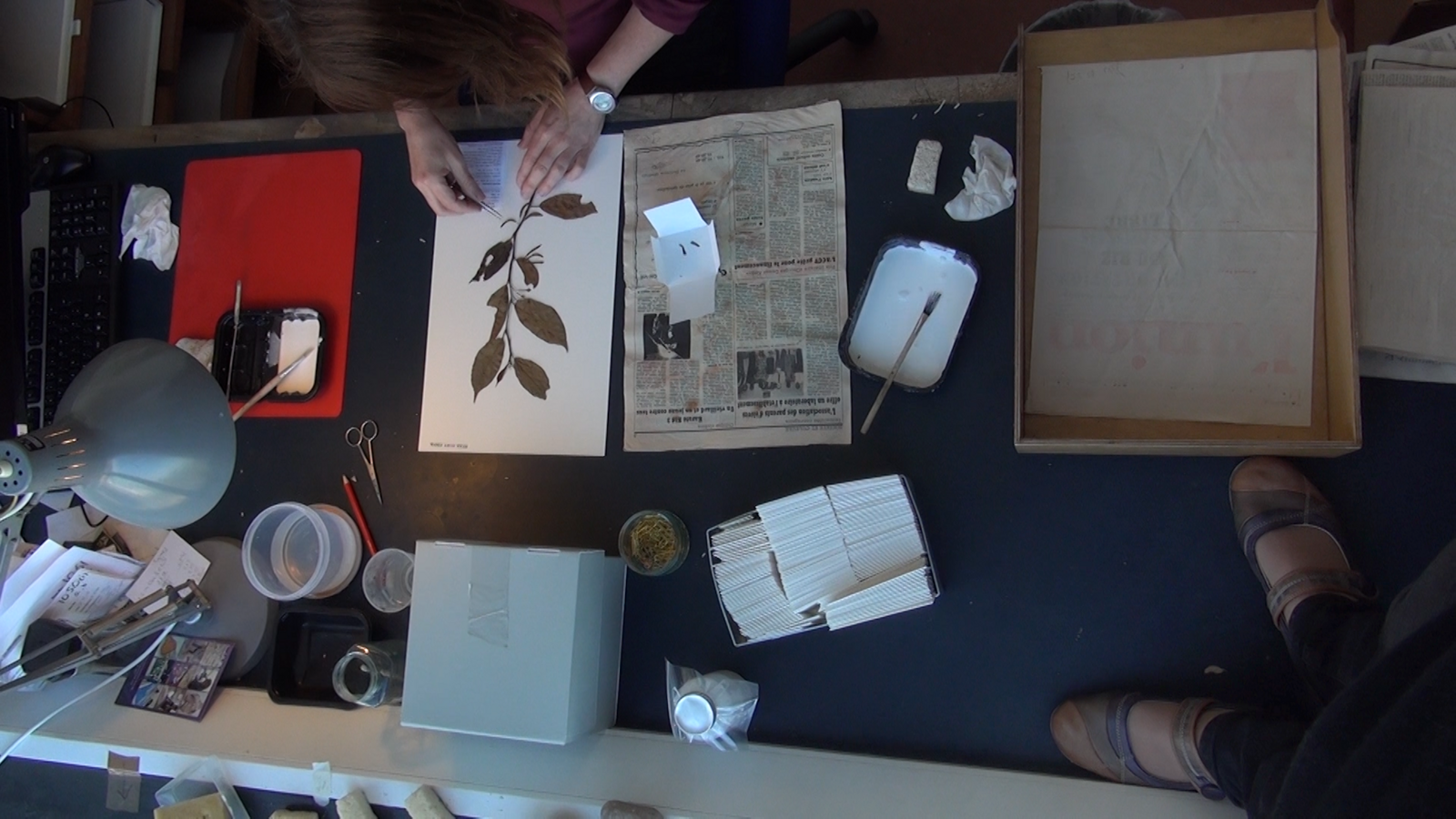

Davis’s work was exhibited in a small room with a vitrine of corresponding specimens from the RBGE herbarium (a subtle gesture of self-implication). A volunteer invigilator engaged visitors in conversation about the work; people took their time, paid attention. Through the door, Mann’s film essay, A Desire For Organic Order (2016), lingered upon the aesthetics of RBGE’s archive and herbarium. The film shows labels and boxes, hands caring for specimens so very gently. A voiceover describes botanic gardens as “processing centers for the biological spoils of exploration.” The film spoke softly, maybe too softly, while the room’s architecture encouraged through-traffic and few people stayed to hear what they needed to hear.

While artists point towards these histories, some botanic gardens are also speaking out but others remain curiously silent. In June 2020, Kew announced plans to decolonize its botanical collection and recently held a significant online conference on botany, trade, and empire. RBGE has now set up several working groups to address racial justice across the institution and a report, produced in collaboration with Kew, will be published this spring. But the Edinburgh institution needs to be more explicit about its own history, such as its connections with the East India Company, an organization known for its role in famine, genocide, slavery, and military oppression. Prominent Edinburgh botanists include James Sutherland (he trained dozens of slave ship surgeons, who would collect plants to be sold for vast profits);5 William Roxburgh, an East India Company surgeon and director of the Calcutta Botanic Garden (founded by the Company for commercial exploitation); and William Wright, founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, owner of enslaved people in Jamaica.

As the colonial institution has shifted to a corporatized one, the questions facing botanic gardens are not confined to history. Trustees and senior management do not reflect the diversity of the constituencies served by the institution, while costly capital projects (such as Edinburgh’s £70 million Biomes Project) are justified in the name of growth and the vague pursuit of “excellence.” Both Kew and Edinburgh continue to collaborate with WWF, even after revelations about the charity’s involvement in brutal neocolonial practices. Some signs throughout Edinburgh’s gardens, and stories across the website, are evasive or patronizing (Roxburgh is described as the “father of Indian botany”) while local knowledge and experience are continually dismissed in order to justify the presence of professional botanists. RBGE explains its presence in China by highlighting its efforts to conserve biodiversity in the face of encroaching rubber plantations. There is no mention of how rubber got to Southeast Asia in the first place. What you can find, if you look carefully, is the work Edinburgh’s botanists are doing in support of this same rubber industry. They’re writing reports on “rubber plantation performance,” expressing concern for “reduced yields” and the loss of millions of dollars’ worth of corporate investment.6 The use of the term “sustainability” here is therefore very slippery. The implication is that it refers to wildlife and biodiversity; in reality, it refers to profits.

While the gardens remain open at the time of writing, the Climate House exhibition of artist films is closed due to Covid-19. The building is currently bestridden by a 45-foot inflatable gold monkey, “an exuberant call for action in saving the planet” by artist and jewelry-maker Lisa Roet. Big, shiny, and bearing a single clearly communicable “message,” Roet’s monkey serves not only to raise awareness of a problem (climate change) but also to position the institution (and “scientific knowledge and expertise” more broadly) as the solution. But for those with even a rudimentary awareness of the activities of botanic gardens, this kind of amnesiac scientism is both predictable and alarming. It is exactly the kind of art I would expect from a colonial-corporate institution, and it is so glaringly at odds with the nuanced, critical work being exhibited inside the building.

This past year, gardens have provided an especially vital refuge for those with the privilege of access. For me, the RBGE has provided an important research resource, a place of great learning, joy, and possibilities for vital connections between human and more-than-human. Yet this should not obscure what kind of institution the botanic garden has been and, in many ways, remains. I’m hopeful that the botanic garden’s engagement with contemporary art can offer far more than some nice visuals and a burnished public image; that meaningful collaboration can provide spaces for genuine agitation or fertile self-contradiction within the institution.

Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book) (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999), 120–143.

Tinde van Andel, “Decolonise the botanical treasure house,” universiteitleiden.nl (5 January 2017), https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/news/2017/01/decolonise-the-botanical-treasure-house; Kate Evans, “Change Species Names to Honor Indigenous Peoples, Not Colonizers, Researchers Say,” Scientific American (3 November 2020), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/change-species-names-to-honor-indigenous-peoples-not-colonizers-researchers-say/; Sui Searle, Instagram www.instagram.com/decolonisethegarden/.

Neil Cooper, “A Change of Climate,” Bella Caledonia (15 October 2020), https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2020/10/15/a-change-of-climate-how-inverleith-house-was-saved-from-permanent-lockdown/.

There is a withering example in Corinne Fowler’s Green Unpleasant Land (London: Peepal Tree Press, 2020) describing the arrival in Tahiti of Joseph Banks, a key figure in the development of Kew Gardens in the eighteenth century.

Kathleen S. Murphy, “Collecting Slave Traders: James Petiver, Natural History, and the British Slave Trade” in The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 70, No. 4 (October 2013), 637–670.

Ahrends A, Hollingsworth PM, Ziegler AD, Fox JM, Chen H, Su Y, Xu J, “Current trends of rubber plantation expansion may threaten biodiversity and livelihoods,” Global Environmental Change (2015) 34:45-58.