It was strange to visit the sixth edition of the Athens Biennale weeks after its kick-off and at times nearly alone. Writers covering megaexhibitions usually move in herds, but this time there was no press conference to provide me with pithy quotes to explain the title, “ANTI,” and no on-site, real-time assessments from fellow critics. I ran into a Greek artist I know shortly after arriving. Later I saw the artist Poka-Yio—a founding director of the first Athens Biennale, “Destroy Athens,” in 2007, and a member of the current edition’s curatorial team, alongside Stefanie Hessler and Kostis Stafylakis—giving a tour. But for the most part it was just me and the work of the biennale’s 100 artists.

This solitary contemplation turned out to be a perfect way to take in this extensive show, which in part functions as a statement on the herd behavior to which the various publics it addresses often succumb. A major thread in “ANTI” is the normalization, appropriation, and capitalization of what society not so long ago considered nonconformist, disruptive, or antiestablishment. The majority of works on view resist quick judgment. They are multilayered, complicated.

This complexity, however, isn’t immediately obvious. “ANTI” opens to a familiar sight: a decaying building as an exhibition space with a lot of post-internet art. The biennale’s main venue is the decommissioned state Telecommunications, Telegrams, and Post (TTT) building, located on Stadiou Street in central Athens, close to three other locations (an old hotel, a derelict library, and an empty storefront) in a geographically compact exhibition. The initial impression is therefore reminiscent of the 9th Berlin Biennale, curated by the collective DIS in 2016. But in the sincerity of its curatorial direction and the provocative bent of the selected works, “ANTI” is less ironic and more dystopian and multifaceted than DIS’s biennale. In the words of the curators’ statement in the dense, reader-like catalogue: “ANTI is a preposition, a position, a person. ANTI is indulgent, ascetic, libertarian. ANTI invests in bitcoins and detests peolitical correctness. ANTI is a contraestablishment politician, a humanist, a creature of our time.”1

The five stories of the TTT are variously reminiscent of school classrooms or 1980s office kitsch; one room, apparently the company president’s chamber, is lined with stained white carpet. “ANTI”’s motifs—queerness, feminism, posthumanism, post-truth, speculative realism, and what the world might look like after the apocalypse—emerge across these spaces. In room after room, most of which are dedicated to individual artists, mediums and statements become a colorful blur. Its potential for overwhelm is compounded by the fact that many hours of video work (and, in my case, missed performances) make viewing the entire biennial impossible unless you live in Athens; some of the time-based pieces are humorous, others long on gravitas. Artists working with technology—Jon Rafman, Yuri Pattison, Marisa Olson, and Ryan Trecartin among them—are well represented, as are collectives and cross-disciplinary practices.

Among the latter are Germany-based (and funded) Peng! Collective, for example, whose representatives sit in a dingy TTT office as “antagonists of corporate PR agencies” for the Civil Financial Regulation Office (2018), calling global financial organizations and asking whomever they reach such questions as: “Do you feel morally conflicted as an individual walking to Goldman Sachs every day?” Documentation of answers and rebuttals are taped to the walls and collated into binders in the adjacent room, while visitors are invited to write new questions. Jacob Hurwitz-Goodman and Daniel Keller’s half-hour documentary The Seasteaders (2018) follows a group of mostly American libertarians meeting to plan a floating eco-city off the coast of Tahiti, selling it to locals as a tool to counteract rising sea levels but in reality exempting themselves from societal obligations like paying taxes, underlining the entitlement of the upper classes and their greenwashing and spin.

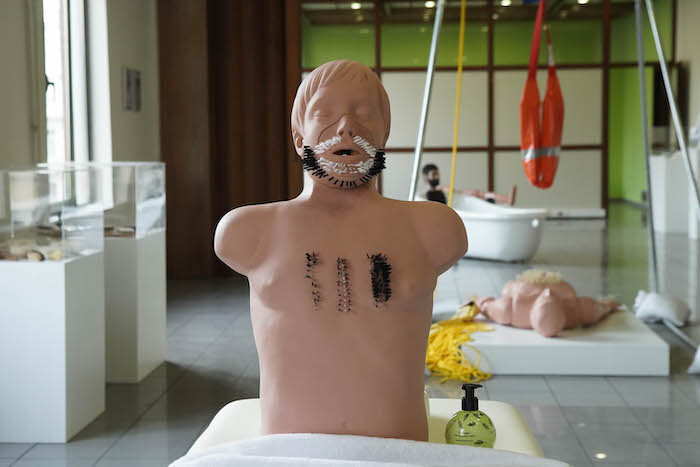

Alongside works that allude to corporate modification of behavior are others that explore ideas of physical “tuning” or self-optimization. In Marianna Simnett’s video The Needle and the Larynx (2016), a vocal surgeon administers a Botox injection to the artist’s throat, paralyzing a muscle in her larynx in order to lower her voice. Meanwhile, Detroit-based Danielle Dean’s video and installation Trainers (2014) depicts a group of American women being primed to become either activists or athletes—a riff on abstract painting, a basketball court, and the set of a Spike Lee–directed Nike commercial from the 1990s. Performance artist Geumhyung Jeong’s installation Spa & Beauty, Athens (2018) is a skewed vision of a spa, where tufted humanoid mannequins lie ready for epilation and a video listing beauty tips drones in the background.

Across the street, in the long-closed Esperia Palace hotel, “ANTI” occupies two floors of offices, conference rooms, and a restaurant and kitchen. In the latter space, costumes and ritualistic objects are strewn in messy piles across steel surfaces and appliances. These objects are leftovers from Panos Sklavenitis’s opening week performance Cargo (2018), in which a “neo-tribal community” in body paint and outlandish costumes paraded through Athens’ streets, bringing to mind underground social movements underway across Europe. Carsten Höller’s short film collages Cinema of Joy and Cinema of Fear (both 2018) evoke the titular states respectively—medial emotional manipulation and meme culture are other topical threads of the biennale. In the foyer and landing are large-format paintings by Miltos Manetas. They at first appear to be abstractions, but on second look reveal themselves to be representations of computer cables. That Manetas’s parents worked in the TTT building feels fitting: the paintings evoke an eerie nostalgia. I was told that, while the Esperia Palace’s future is unclear, the TTT building—a symbol of the shift from analogue to digital communication—will be converted into a five-star hotel.

While “ANTI” engages with global, late-capitalist issues, its underlying tenor is local. Greece has profoundly changed between the first Athens Biennale in 2007 and the arrival of Documenta 14 ten years later. The eurozone’s economic bailout of Greece formally ended on August 20, 2018, yet crisis and austerity remain. This decade-plus state of exception was bracketed by two senseless murders that received a relevant media attention: the first of 15-year-old student Alexandros Grigoropoulos by a policeman on December 6, 2008, which ignited riots in Athens; the second, of LGBTQ activist and artist Zak “Zackie O” Kostopoulos, to whom this biennial is dedicated, in September 2018.

In the catalogue, the curators lay out their mission: “This biennial aims to instigate the experience of ambiguity, polarity and contrariness inherent in ‘ANTI’ by lubricating its absurd personifications. The exhibition device becomes a purgatory without a purge.”2 My major criticism is that formats in the TTT building, with its succession of similarly sized and drably furnished office spaces, can become repetitive—several videos of similar duration and aesthetics, installed near each other, reduce the impact of each. This aside, the “exhibition device” is successful. The venues conjure a poignant sense of limbo, while the works within them evoke a profound sense of unease without quite eliciting despair—some even manage to provide glimmers of levity. Purgatory, after all, is an intermediate space or state meant for contemplation with the ultimate goal of transcendence: its punishment is not final but transitory. I’m reminded of Florence Jung’s Jung 53 (2017). It’s a door off a landing in the TTT building that’s slightly ajar. Push on it, even lightly, and something—or someone—pushes back. How to respond? Keep pushing against an invisible force in an attempt to enter an unknown space, or skittishly move on and find another way? Jung’s piece represents a broader comment on contemporary conditions made by “ANTI” as a whole—that obstacles are as unclear as possible outcomes, while the choice to oppose or acquiesce, to act or react, to work or to wait, is internal, complex, and always fraught.

Stefanie Hessler, Poka-Yio, and Kostis Stafylakis, “ANTI,” in ANTI – AB6 Athens Biennale 2018 (Athens: The Athens Biennale, 2018), 23.

Ibid.