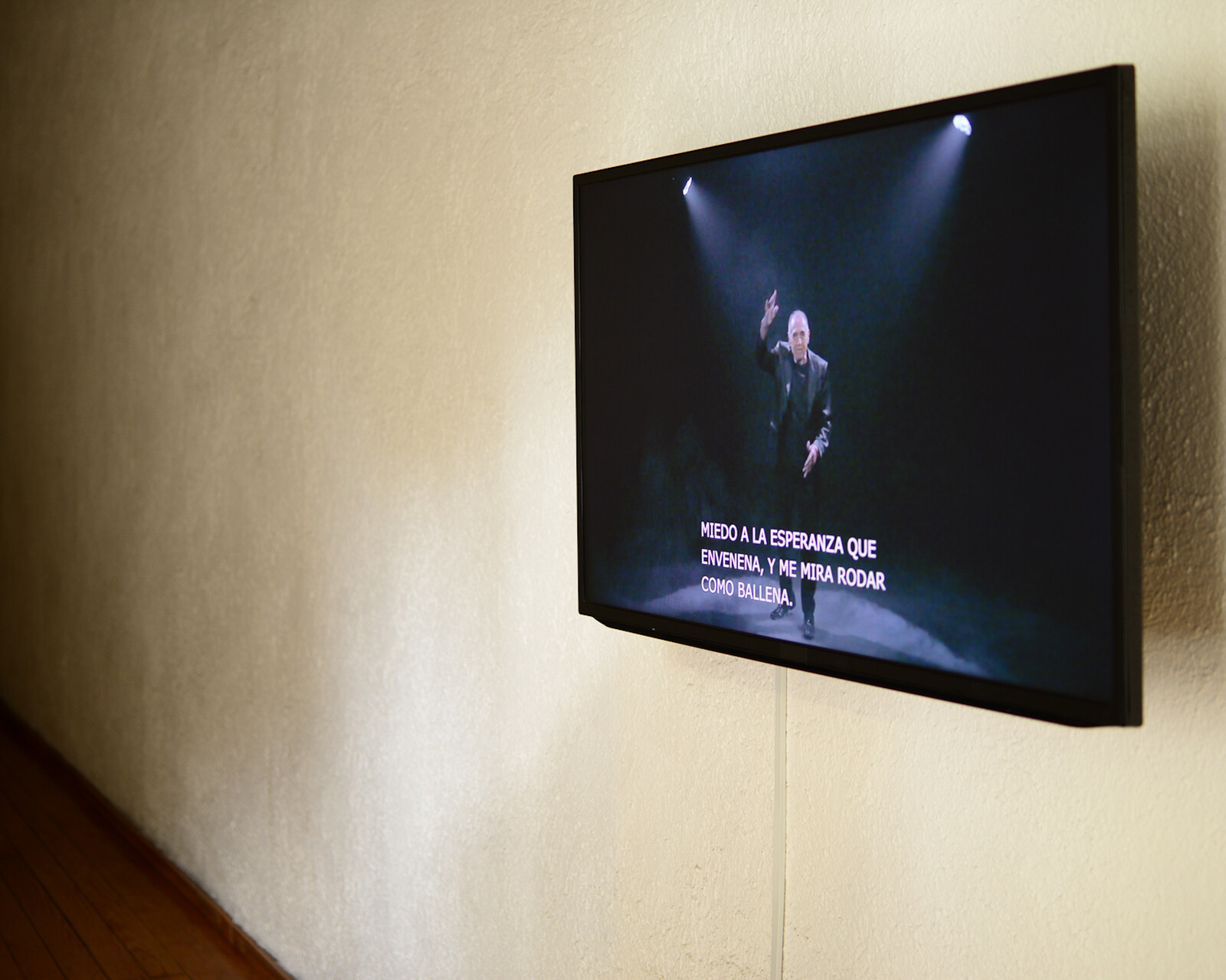

Mexico City’s fall openings are marked by a theatrical turn. The most overt expression is “Destino” [Destiny], organized by Mario García Torres at Museo Experimental El Eco. Displayed on a screen in the museum’s narrow entranceway is Disculpa [Apology] (2022), a video by García Torres and Eduardo Donjuan that sets the scene. The buffoonish face of Alejandro Suárez—a comedian well-known to Mexicans born before the turn of the millennium—performs a monologue in a painstaking, over-acted way. He goes on about his agent bringing him the offer to participate in this show, talks of “an air of the avant-garde” as a reason for accepting the invitation, and digresses on the similarities between art and spectacle. There are passing references to the Museo Experimental El Eco’s history: first established as an art institution in the 1950s, it later became a gay bar, a punk bar, a restaurant, a boxing gym, and a small theater, before reverting to its original function. At one point, Suárez recites a poem and then dances enthusiastically—it’s equal parts kitsch and unsettling to watch. He touches on some of Mario García Torres’s enduring fixations, evident in his earlier monologues and performances including I Am Not a Flopper (2007) and The Causality of Hesitance (2015): time, failure, and disappointment.

The show incorporates all of these, yet its elaborate yet haphazard staging renders the artist-curator’s intentions opaque. Further inside the gallery is a makeshift auditorium: a staggered seating area on one side and a stage framed by the steel beams of lighting rigs on the other, with mirrored panels at the back of the stage. This stage is populated by a few sculptures by some well-known artists. Untitled (2010), a white, nude mannequin trapped inside an iridescent cylinder is the work of Heimo Zobernig; Dark Table with Light (2007), a monochromatic assemblage of a floor lamp tilted on a table with butterfly wings, is by Tunga; and a small, delicate piece in brass and translucent fabric, La rivoluzione dogmatica (1969) by Fausto Melotti, sits just behind a wall, inconspicuous under dark blue light. The objects appear neglected, awaiting some kind of incantation to re-animate them. This feeling heightens the sense that a stage is a far-from-ideal environment for appreciating art. The dim surroundings mean the works are hard to read, while the laugh tracks, fake claps, and harsh illumination of theater lights intensify the sense that these works are being upstaged. They can’t catch a break. I quickly realize I’m missing something (if not everything) by not attending the “activating monologue” events. But is it too much to ask for the objects to do some telling of their own?

At House of Gaga, Alex Hubbard’s art objects are similarly put to work, but in a more relaxed manner. They imitate the aesthetics of marisquerías, the loudly decorated seafood restaurants found all over Mexico. One can hear the salsa and smell the michelada when looking at his loosely delineated, brightly colored paintings of lobsters and beers (Exotic Parameters, 2022), and swimming shrimp (Garden Painting I [Tandem], 2022). They hang outdoors at Gaga’s private garden, barely protected by candy-striped awnings left over from the city’s freakishly long rainy season, which only recently ended.

Two similarly striped folding chairs sit in front of each painting, a little out of touch with the gray skies we’ve endured. The leisurely painting installations also contrast strongly with their counterparts inside the gallery, where five enormous, abstract expressionist paintings hang. Where the garden group evokes the fantastic domesticity of a vacation; the inside group is all dismembered mechanics, its colors toxic-spillage bright, its edges ragged with hardened latex, the transparency on the layers improbable, artificial. If these paintings are at work, it seems they are aware of—and enjoying—their oppression. The theatrical, comparative framing of both groups of paintings provide an ironic commentary on spectatorship, instead of merely suffocating the art. A highlight is Disturbia (2022), centering the open jaws of a machine in fumes of noxious teals and browns against a fiery orange background, which features pretty reflections of metal pipes—and some ominous blood stains and cobwebs, for good measure. Hubbard’s paintings exert themselves, even when pretending to relax.

Emanuele Marcuccio’s “Dream pop,” at Lodos, takes on scenographic themes in a more subtle yet effective way. The show is succinct: only a few components lead the spectator to figure out they are standing in a set—though what the set is for remains unclear. Half the walls are covered in kraft paper, indicating the crafty quality of most props, but also cleverly creating a visual divide, an inside versus an outside. Right on this division hang four pictures, collectively titled “Sugar rush” (2022) and created by Marcuccio with fashion photographer Marc Asekhame.

In the images, a young man stands around in a domestic interior, a sunny kitchen somewhere in Southern Europe. In the first two he is alone: looking over the photographer’s shoulder with a fashionable pout in one, staring out a window in the other. The second pair shows only close-ups, a sugar bowl and a cup resting on a washing machine, the torsos of people standing around a table, a pair of hands. These images are interpolated with a few enigmatic objects, like a minimalist fake window made out of aluminum and steel (Window, 2022), the literal superposition of a blue sheet with a black grid on top. Or the evocative juxtapositions of Comet in a box (2022) and Comets in a box (2022). Both almost as simple as they sound, these standard aluminum boxes are stuffed with rudimentary comet shapes made out of shiny red and white vinyl fabric. That these equally mythical and modest objects coexist with the reasonable, predictable interiors of the images only emphasizes the idea of existing in an imaginary place: the kind of fiction, in other words, that a theatrical set supports.

Perhaps Marcuccio’s experiment is the most effective example of this theatrical turn because the minimal staging allows the art room to maneuver and its audience space to interpret. My sense is that the theatricality of these and other recent shows across Mexico City is about “activating” the art object—putting it to work. The intentions for this range from building a fiction or a spectacle, to attracting an audience, embellishing the work or explicating its many possible readings. But sometimes the effect is to dumb down, make the work impenetrable, or reduce individual works of art to the status of afterthoughts in a much grander scheme. It might be worth remembering, in staging them, that works of art are able to act on their own.