“Have you ever wanted to be… savage… wild… free?” asks a nylon banner in New Red Order’s Recruitment Station (2020–21). Mimicking the pat visual grammar of military recruiting tables, the multimedia booth—modelled on a portable trade show exhibit—solicits volunteer “informants” to join the self-styled “public secret society.” With plentiful wit, Recruitment Station frames a contradiction that haunts this exhibition of Indigenous futurisms: modernity has consistently subjugated Indigenous peoples, yet is driven by a sublimated desire for Indigeneity.

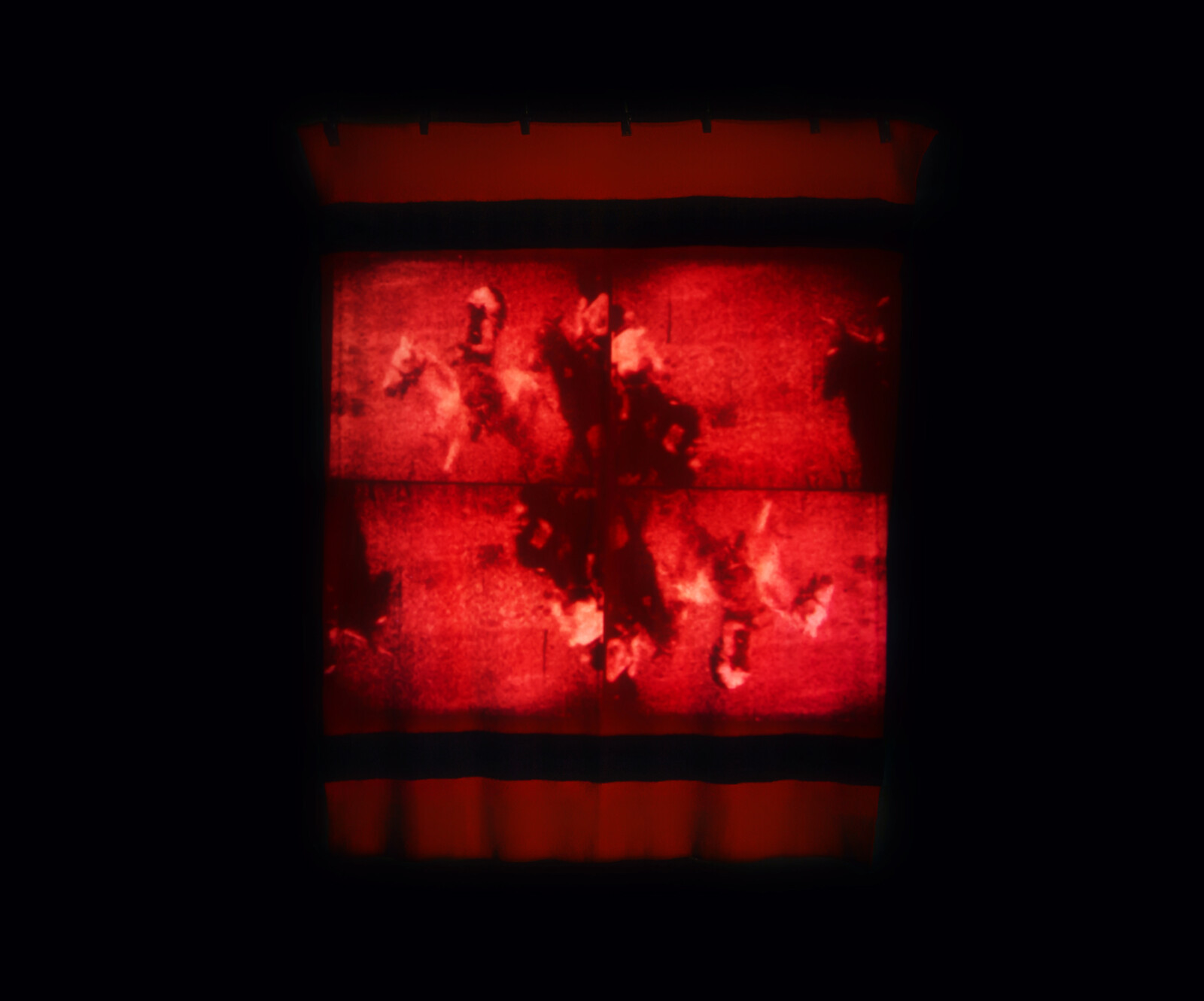

Addressing this bind, “Speculations on the Infrared” explores the ways in which Indigenous artists are dismantling settler colonial fantasies by asserting decolonized futures. Alan Michelson, a Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, here displays Pehin Hanska ktepi (They killed Long Hair) (2021). The installation projects archival film of Indigenous veterans of the Battle of the Greasy Grass onto an antique wool trade blanket. Known in the settler mythos as Custer’s Last Stand, this saw several Plains tribes unite to defeat forces from the US Army during the Great Sioux War of 1876. The gridded, looping footage, recorded during a parade celebrating the battle’s fiftieth anniversary in 1926, recalls a winter count: a pictorial record used by Plains tribes to commemorate important events. Outlining the generations of rebellion that preceded the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock in 2016, Nick Estes of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe has attested that, in the eyes of Indigenous warriors and water protectors, “our history is the future.”1 Bathed in a warm red filter, Michelson’s affecting installation evokes Estes’s words as it visualizes ancestral resistance.

Fever Dream (2021), an interactive installation by Oglála Lakȟóta artist Suzanne Kite, who exhibits under her surname, and Devin Ronneberg, who is of Maoli/Okinawan descent, critiques the spectacular role of conspiracy theories in overwriting Indigenous cultural achievements. The artwork utilizes lidar—a remote sensing technique in which invisible laser light pulses measure distance—to detect the presence of a visitor’s body: a CRT monitor shows film, television, and social media footage, much of it culled from YouTube, that changes with the visitor’s proximity. In its haptic sensibility, the artwork destabilizes the subject/object dichotomy reified in European traditions of viewership and knowledge production. AI-generated text, woven together from a library of anticolonial literature, subtitles the video, glitching and reworking the colonial script.

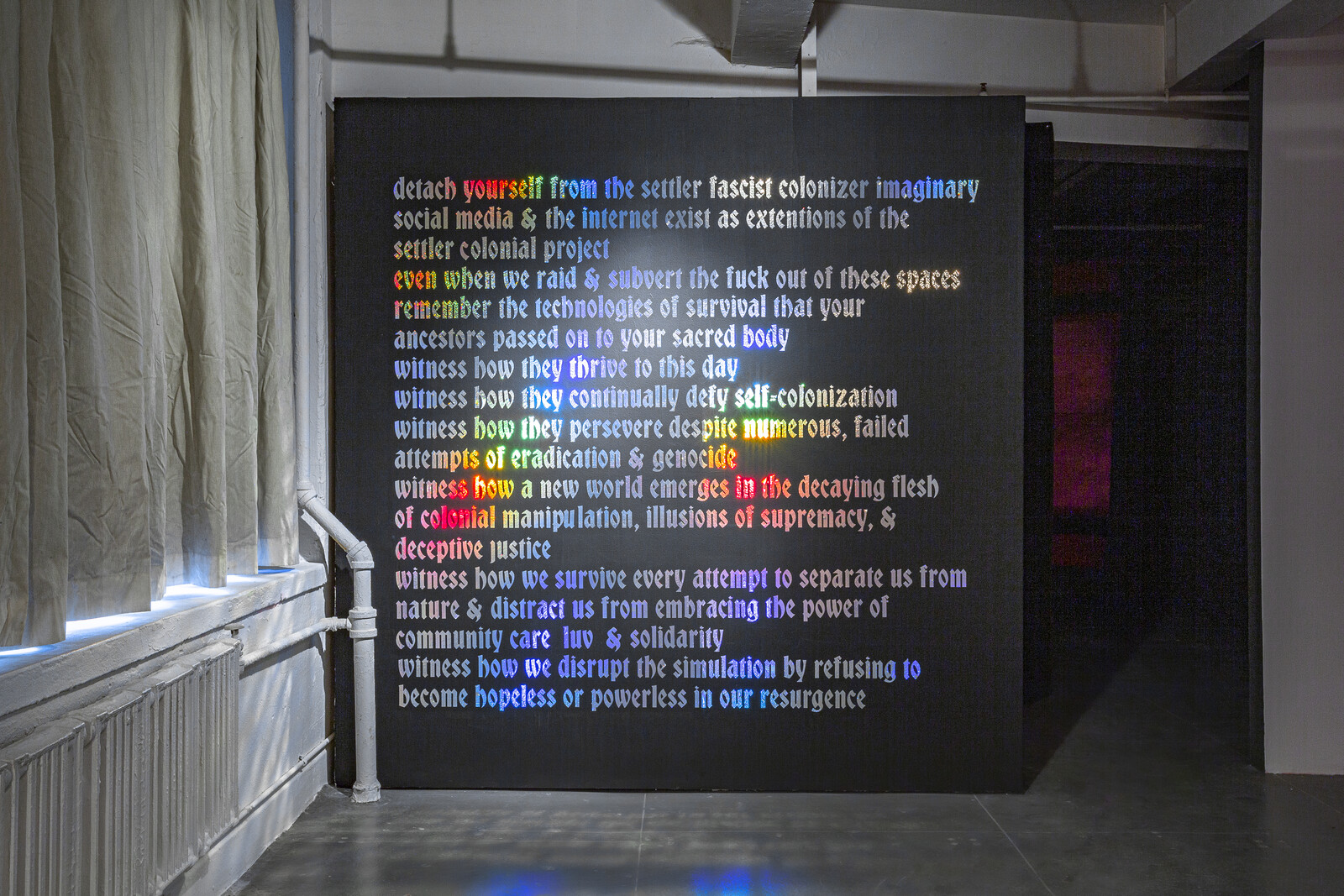

Dancing by Fever Dream is the lucidly titled disrupt the settler colonial simulation (2020), a wall text piece by Diné artist Demian DinéYazhi´ that lyricizes the exhibition’s political claims. The verse’s final couplet asserts: “witness how we disrupt the simulation by refusing to / become hopeless or powerless in our resurgence.” Its metallic vinyl lettering refracts the gallery’s spot lighting, inducing a rainbow shimmer. As a prefix, infra- connotes the space below a given scale; infrared light is beyond the visible spectrum. Symbolically, the color red denotes Indigenous liberation, as articulated in the revolutionary Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s, and furthered today by organizations such as The Red Nation. The infrared of the exhibition’s title, then, describes the aesthetic spectrum below and beyond the settler colonial visual order. DinéYazhi´’s iridescent decal stretches this suggestive metaphor, queering the red edge of visibility.

In her 2014 book Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of the Settler States, Mohawk political anthropologist Audra Simpson questions the rhetoric of recognition, which she characterizes as “the gentler form, perhaps, or the least corporeally violent way of managing Indians and their difference, a multicultural solution to the settlers’ Indian problem.” To locate her powerful critique in the realm of contemporary art, we might observe that broadening settler platforms to support Indigenous artists frequently effects “an impossible and also tricky beneficence that actually may extend forms of settlement through the language and practice of, at times, nearly impossible but seemingly democratic inclusion.”2 Indeed, catchily quipping on the “alien nation” and its “urge to merge,” New Red Order’s display provocatively foregrounds the possessive logic of the progressive state. What is inclusion, if not invasion by another name?

Media collective Unicorn Riot’s 2019 video Infrared Aerial Surveillance from Standing Rock, 2016-2017 places this fiercely unresolved tension into relief. The two-hour document features infrared imagery, captured by the North Dakota Highway Patrol, that tracks water protectors at Standing Rock, and underscores the bellicose response of the US to a gathering of the land’s rightful stewards. Beautifully, the surveilled protestors slip from view as bison, cookfire smoke, and even tear gas conceal body temperatures from the thermographic camera. With similar grace, each work in “Speculations on the Infrared” refuses colonial recognition premised on a tragic binary of alterity or disappearance, instead gesturing to an expanded sensorium, rooted in relations with the land and shaped by intergenerational solidarity. These speculations manifest concrete Indigenous futures.

Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (London: Verso, 2019).

Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014). 20.