Achille Mbembe describes the archive as a “cemetery”: a burial ground in which “fragments of lives and pieces of time are interred.”1 Opening up Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s Resurrection Lands (2020)—an online game and speculative digital archive of Black trans experience—I am reminded of this description.2 Aside from the obvious conceptual resonance between the paper graveyard and the digital afterlife conjured on screen, in telling the game’s fabulated backstory my disembodied guide seems to echo the central paradox Mbembe identifies. That is: we need the archive to remember, but it is also a tool for forgetting. Or, as Brathwaite-Shirley’s introductory voiceover asks me: “how [is] it possible to store [someone] in a world that had once erased [them]?”

A tentative answer to the difficulty of archiving trans lives might lie in the digital realm. The internet’s potential as a place for self-narration was recognized early by trans creators. In the 1990s the nascent World Wide Web was a playground, a site of both creation and distribution that encouraged new modes of participation and facilitated formal experiment. It was not just that this “newness” opened up space to document trans experiences—apparently (although not actually) in a world as yet untainted by the social codes of IRL living—but the mutability of digital interfaces themselves seemed to speak to a sense of disjointed embodiment. Online, the possibilities for presentation were not limited by a physical body and its chemical and anatomical fixities. Instead the internet offered a kind of “Ground Zero” for reinvention: new personas could be created at the click of a mouse, pages deleted and refreshed—everyone with the freedom to change and enact this transformation at will.

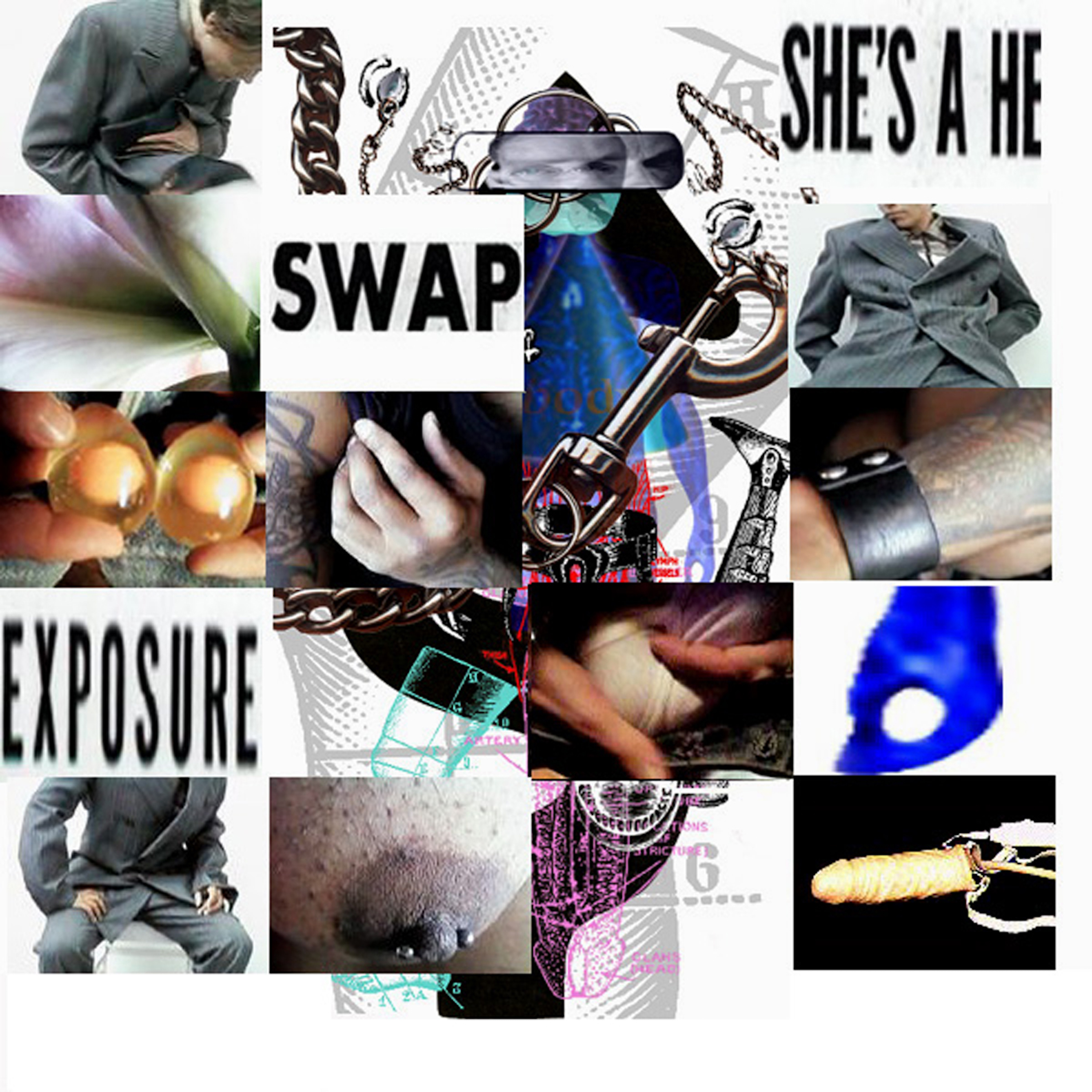

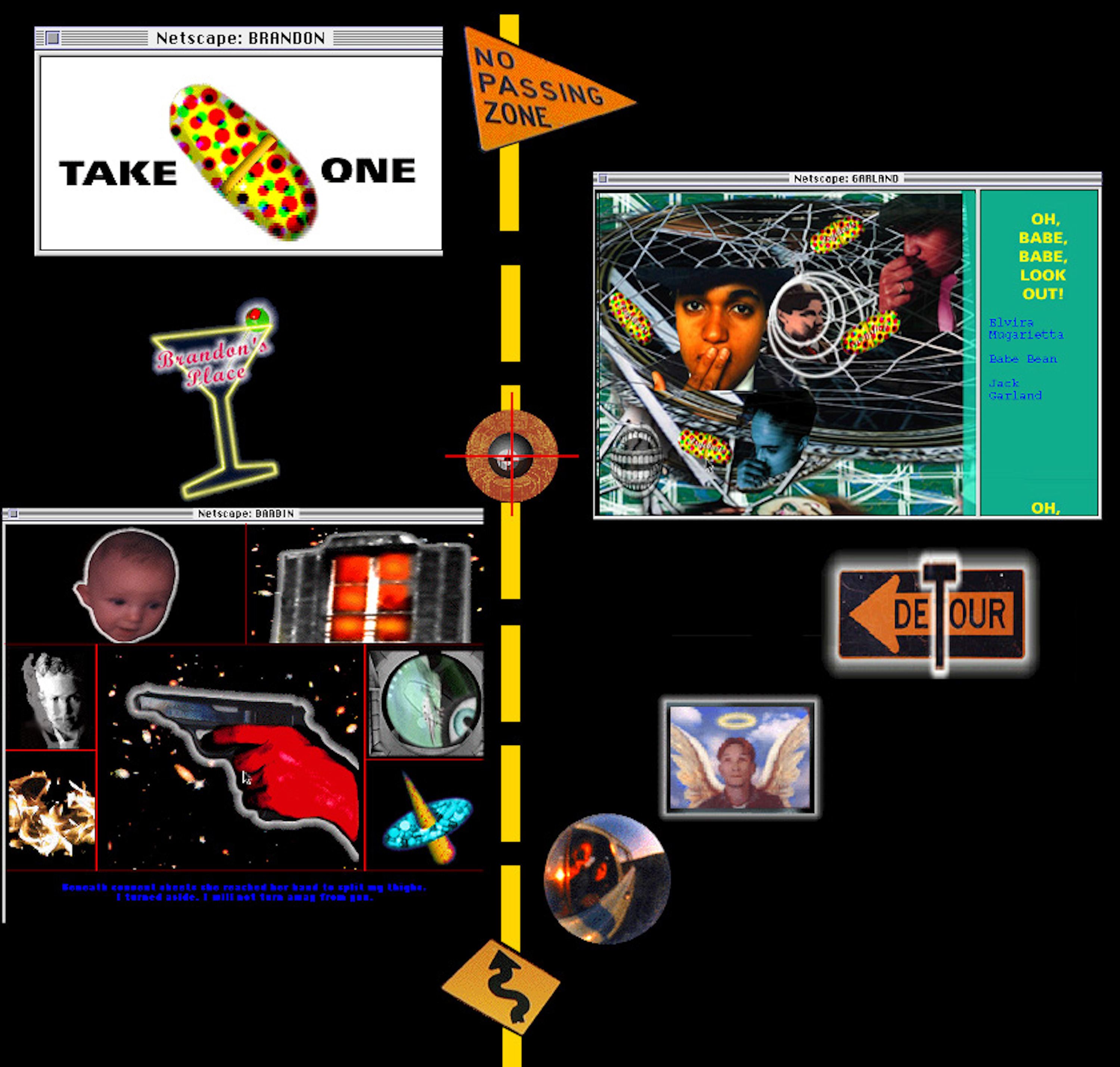

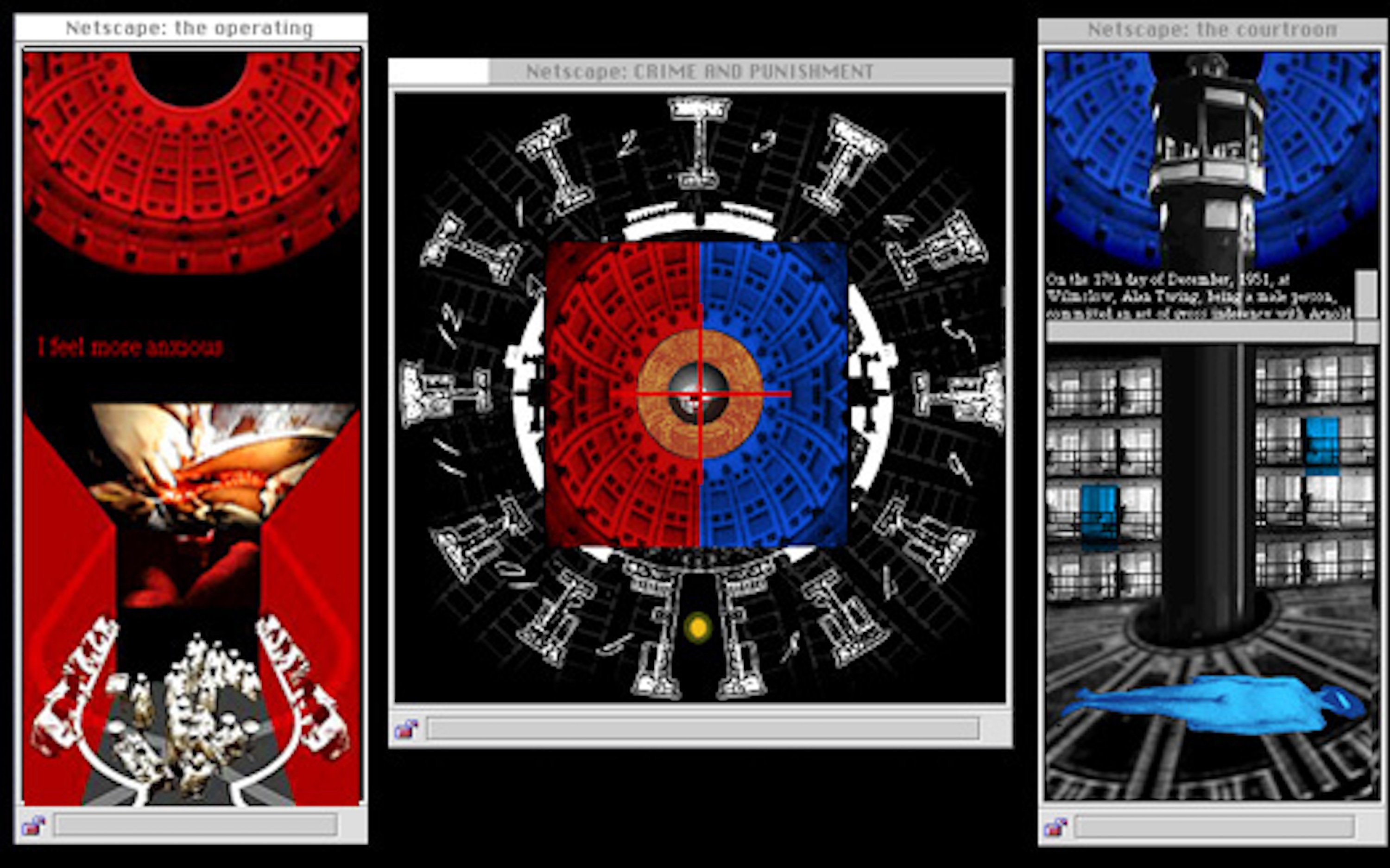

Shu Lea Cheang’s 1998–99 work Brandon mobilizes this sympathy between the formal parameters of the web and forms of trans life to produce a hyperlinked archive and nonlinear narrative of gender nonconformity. At its nucleus is the story of Brandon Teena, a young transgender man who was raped and later murdered (along with Phillip DeVine and Lisa Lambert) in Nebraska in 1993. The work spirals outward from these events as the viewer moves erratically through various interfaces; from flickering image-tiles which morph under the mouse to now-dead chatrooms populated by eerie bots, and the final Panopticon—twin towers, one red, one blue, representing a prison and an operating theatre.

Being based online facilitates Brandon’s collaborative and non-hierarchical operations. The complexity of its multifaceted design required the input of many programmers, writers, artists, and other transgender practitioners.3 Brandon is the product of collective authorship, much like the web itself. But sovereignty is also extended to the viewer as they navigate the pages’ un-signposted entrances and exits, exploring each interface without guidance or explicit rules. The autonomy afforded the multiple actors whose decisions comprise Brandon foregrounds the agency of trans people to narrate and direct our own stories, and the need to have that creativity respected. The viewer must go at the work’s pace, waiting for its internal timer to trigger the next page; we wait for Brandon to be ready to invite us further in.

This staggered intimacy is all the more important because, online, the work can be accessed by anybody, regardless of their gender identity. Brandon is always therefore speaking to two audiences at once—one cis- and one trans—often with directly competing needs. In many ways the work self-consciously negotiates that fraught path, inserting itself into the legal and medical institutions it identifies as fatal. Brandon hosted two live participatory events: the performative installation Digi Gender Social Body: Under the Knife, Under the Spell of Anaesthesia produced with the Waag Institute for their Theatrum Anatomicum (the site of the first public dissections in Europe), and the virtual court and netcast forum Would the Jurors Please Stand Up? Crime and Punishment as Net Spectacle with Harvard University’s Institute on Arts and Civic Dialogue. In these spaces, Brandon’s shimmering, hyperlinking existence represented a kind of shield or cipher, allowing trans embodiment to go where actual gender-variant people would be brutalized and humiliated. In contrast to Mbembe’s cemetery, the work proposes a living architecture: an archive that works through and around live bodies mediated via a malleable digital sphere.

It might be more proper to say “life-like” as well as “living.” At the heart of the work lies a dead body—that of the real Brandon Teena. Brandon carries its namesake ambivalently. Playing its narrative, I am torn in two; amazed by and grateful for this reanimation, yet disturbed by the fact that Brandon did not, could not, consent to his involvement. Mbembe speaks of his concern that the historian restores life only to use it as a “prop,” dispossessing the autonomy and authority of the archived person in order to speak over them, not with.4 Online, with the addition of phantasmic data-bodies and digital projections of identity, this distinction between reincarnation and puppetry becomes even more blurred. In Resurrection Lands a buried Black trans ancestor voices their fear of being disinterred, dug up only to be reburied whilst their copy is pulled from the earth by loving hands and kind words.

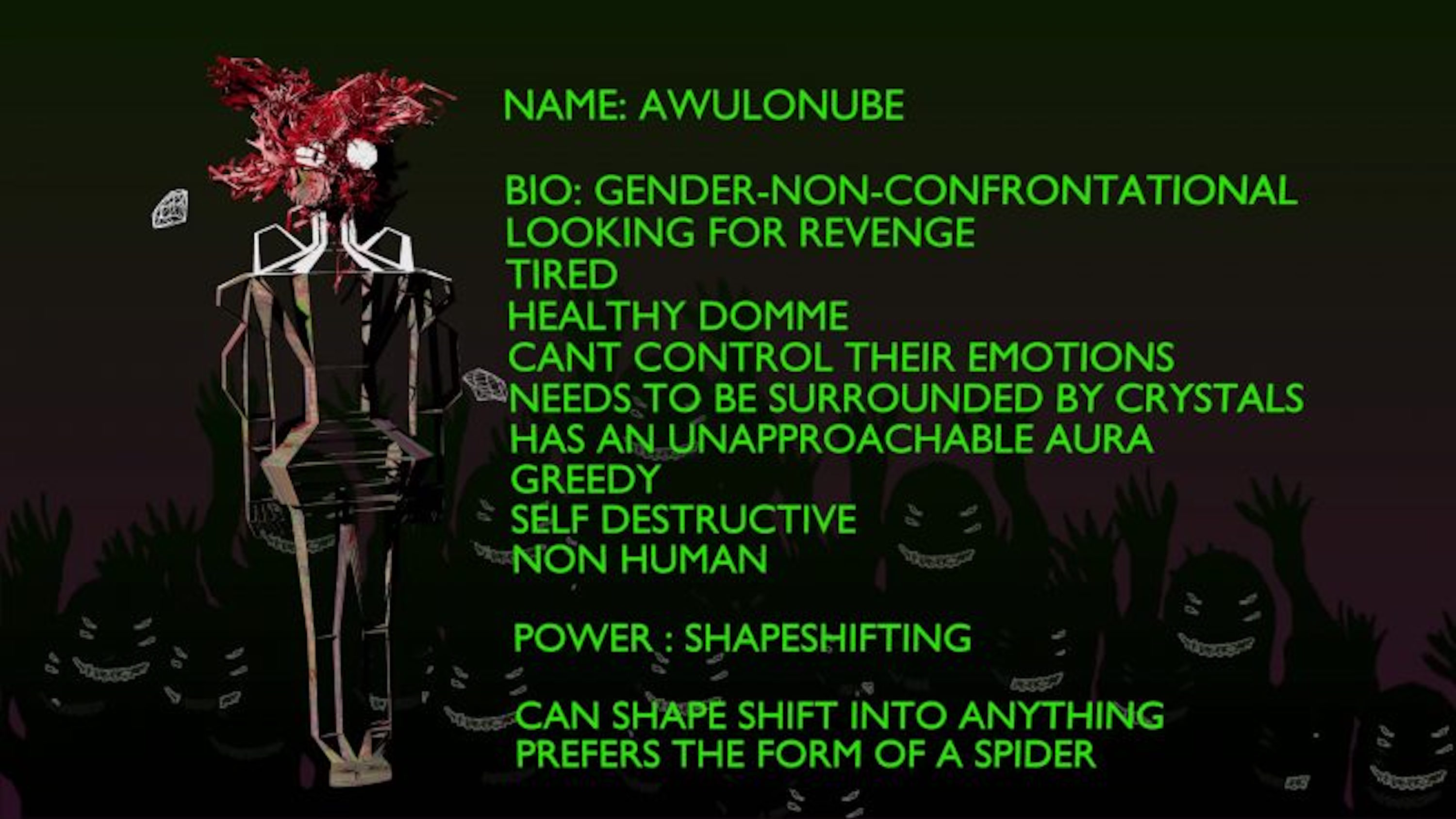

Brathwaite-Shirley’s Resurrection Lands is part of an ongoing project to construct a different archive—one made by and for Black trans people, constructed not around trauma but on the revitalization of ancestors and the speculative vision of a world now able to hold them.5 This is made literal in Brathwaite-Shirley’s work Black Trans Archive (2020), in which the viewer’s first task is to assist in the resurrection and “uploading” of an unnamed Black trans ancestor into a digital avatar. The baldness of this act brings with it a visceral sense of the negotiation of online space as a physical body. Whilst viewers of Brandon are encouraged to move through the work in a way that is consistent with the disembodied godlike observer behind the screen, in Black Trans Archive and Resurrection Lands we enter as a POV character forced to confront our own position in the space.

Unlike Shu Lea Cheang, Brathwaite-Shirley actively codes the viewer’s identity into our experience of the work. Whereas cis- and trans viewers of Brandon engage with exactly the same narrative, Resurrection Lands and Black Trans Archive present different experiences depending on one’s answer to an initial identifying question. Respect is not passively assumed or proscribed, but it is a tribute we must consciously consent to give, while encountering the disturbing possibility that because we may be white (or cis-) we are unable to do so—or, that our word on the matter is not enough. Resurrection Lands is a response to those who would “dine out” on Black trauma or engage in what Brathwaite-Shirley has called “Trans Tourism,” never forgetting that the archive’s burial ground is a resource some wish to mine for their own profit. To those viewers, the “consumers” who are neither Black nor trans, the work presents a washed-out, degraded interface, barring entry to certain areas.

As such, Resurrection Lands has a different orientation to most archives. Its responsibility is not to the visitor per se, but to the memories and emotions stored within its code. If the traditional archive exists to help the historian in their gravedigging endeavors, Resurrection Lands proposes an infrastructure capable of caring for those interred and their descendants. How to protect those held within is a question archivists of all collections should be asking. How can we best serve all those whose remains have been deposited here and be hospitable to their autonomy and fluidity, holding space for change—of both the subject and the language used to label and find—a flexibility usually anathema to the rigidity of record-keeping?

What Brandon and Resurrection Lands make clear is that to do this entails building a whole new architecture: one that is not static and hierarchic, based on the external assignation of “identities” that group and divide objects, but rather one that privileges community over categorization, and is able to welcome flexibility, change, and self-definition. One such example of this networked approach can be found in the Digital Transgender Archive (DTA), founded in 2015 by K. J. Rawson and Nick Matte. To imagine this project as an archive is slightly misleading: the DTA functions by connecting rather than collecting. It holds no material itself, but rather virtually merges collections deposited in other institutions, providing a single entry point to hundreds of disparate archives via its search engine.

Rawson and Matte have constructed a gateway rather than a building: a way in which trans histories can be accessed from outside the rigid disciplinary framework in which they are often stored, which allows them to be brought into relation with each other and with the newly empowered researcher. But the question remains as to whether (and how) we could bring this approach to more collections than those currently connected by the DTA: collections which are not specifically marked as trans (a label that is often entangled with those given by law-enforcement or the medical establishment) but that in all likelihood contain gender-variant lives.

A way towards this horizon may be found in archives already being made. Over the past two years I have been assisting Hackney-based reading room and project space Banner Repeater build the Digital Archive of Artists’ Publishing (DAAP): an interactive, user-driven, searchable database of artists’ books and publications. Much like the DTA, the DAAP is aimed at connecting existing collections. However, instead of being held to the rigid bibliographic standards set and adhered to by the institutions with which Rawson and Matte collaborate, this archive uses linked data, enabling a more flexible database with the potential to change and develop.

The DAAP is non-hierarchical, emerging directly out of a community of artists, publishers, and creative practitioners who will continue to construct the archive as users, adding objects and anecdotal histories directly to the database following a collectively authored code of conduct. The autonomy given to the user to archive themselves or their community, the lack of fixity that is built into its very architecture: one can imagine how an institutional archive built on these principles could run alongside the work done by Brandon and Resurrection Lands to create alternate online spaces that can hold trans life rather than condemn us to death and burial.

The author would like to encourage donations to the Black Trans Foundation from those who are able to do so.

Achille Mbembe, A., “The Power of the Archive and its Limits” in Carolyn Hamilton , C., et. al. (eds.) Refiguring the Archive (Cape Town: Springer, 2002), 19.

Resurrection Lands can be accessed online via Focal Point Gallery’s website until 17th January: https://www.fpg.org.uk/exhibition/resurrection-land/.

Abbra Kotlarczyk, “Radical Living Archives and Trans* Embodiment: Shu Lea Cheang’s Brandon” in TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2/4, 2015, 686.

Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and its Limits,” in Carolyn Hamilton et. al. (ed.) Refiguring the Archive (Cape Town: Springer, 2002), 25–26.

Tamara Hart, “Dining on trauma: Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley talks trans-tourism, motherhood, & being a ‘Freaky Friday everyday’” in AQNB, 10 August 2020, https://www.aqnb.com/2020/08/10/dining-on-trauma-danielle-brathwaite-shirley-on-trans-tourism-motherhood-and-being-a-freaky-friday-everyday/.