February 1–5, 2023

“Alexa, I used to bark at you, now I say please and thank you.” This is artist duo !Mediengruppe Bitnik describing their work Alexiety (2018), featuring music written for the virtual assistant. It begins as a love song between user and device, then gradually gets darker. They discuss the work during a panel about the “Digital Middleman” with artists Farzin Lofti-Jam and Simone C Niquille, moderated by Silvio Lorusso, as part of the five-day Transmediale festival at the Akademie der Künste, which is complemented by exhibitions at the AdK, as well as a citywide public art project, “Out of Scale.”

The Digital Middleman panel, its participants explain, developed during preparation from a larger discussion of our relationships to the platforms and corporations that shape our digital lives to a conversation about how companies like Google and Apple have come into our homes. Transmediale, the veteran arts festival begun in the late 1990s (with precursors dating back to the ’80s), has grown from a focus on the relationship between art and technology to a reflection on how our interactions with technology are now conditioned by its developments. Many of the works on view and panels in the festival considered advancements in, for example, machine seeing and artificial intelligence, exploring a shifting world, and deciphering an image landscape produced by technologies humans are designing to move farther and farther away from what we used to think of as vision.

You’d be forgiven for smiling when seeing a life-size Pokémon right at the entrance to the festival, but it’s not just a wink at popular culture’s obsession with augmented reality games, it’s Neïl Beloufa’s Host B trying to reach out to its audience (2021), an interactive sculpture that takes over your Twitter account and tweets for you (if you scanned a QR code, which I didn’t because I don’t trust cartoon characters with my social media accounts). Host B is something between a museum docent, a parasite, and a critique on surveillance and data collection. In another interactive work, CAON–control and optimize nature (2022/23), a two-channel simulation by Marc Lee, viewers use a smartphone to navigate an imaginary world in which AI and 3D printing are used to manage the natural environment. It feels weirdly dark though it’s not a cautionary tale, just an imagining of another end of technology.

Niquille, who in the panel discussion reminded listeners that “tech is a solution to a problem you didn’t know you had,” is showing her work duckrabbit.tv (2022/23) in a two-person exhibition with Alan Butler in the upstairs gallery. Their works invade each other: Butler’s Unnecessary Journeys (2023) is a 3D video simulation shown on a long convex screen modelled on the topology of Yosemite National Park in California. We see a weather reporter trying to speak above an intense storm against an audio of a loud disturbing hum (actually the sound of computer fans). Sometimes the screen is shared with Niquille’s duckrabbits, little animated characters based on the famous nineteenth-century optical illusion, who jocularly discuss their lives. They break the anxiety of Butler’s natural landscape, introducing ambiguity and a questioning of what it is we see.

Trevor Paglen has written that we live in an age of “machine realism,” when more images are viewed by autonomous systems interpreting them than by any other way of looking. Paglen describes it as a new category of vision. This, he writes, is alarming since “it robs us of the possibility of self-determination by commandeering the power to decide the meaning of things.”1

The multiplicity of artworks and discourse at Transmediale resists being flattened to the note on my phone that started with “it all says something about our interaction with technologies in the age of machine seeing.” What was most interesting over the festival was how artists and theorists discussed the way media shapes the news (like artist Alaa Mansour, who showed videos of video games simulating American war in far-flung regions in a panel titled “How an Image Matters”) and how images shape our histories. A talk by Robert Gerard Pietrusko explored how the CIA used satellite imagery to gauge intelligence about the health of Communist economies based on their grain production. He analyzes false color in these images, the saturated reds, pinks, and cyans colored onto aerial overviews, offering what he refers to as “a hyper-aestheticized depiction of landscapes.” Pietrusko questions how these historical images are readable now that they are divorced from their original codes, with red signifying barley or pink for wheat. I wonder: Do we look at historical aerial images differently now that we can see Google Earth satellite images of our own backyards?

Perception follows technology. In his performance The View from Above Takes My Breath Away – Fully (2023), Nadim Choufi presents another historical example of aerial imagery used for political purposes. UNESCO’s Arid Zones program in the 1950s was meant to solve global hunger by managing water resources in arid areas, specifically in the Middle East, in an attempt to make them fertile. One of the lines that haunts me was spoken by a UNESCO official, who said (of the “arid” Middle East) that, “somewhere here was the Garden of Eden.” In Choufi’s performance, he sits at a desk reading a text that interposes this information with the story of Epcot Center in Florida: initiated in the 1960s as an experimental planned perfect community, it ended up becoming a theme park about the future. On screens behind him are images of the desert, Disneyland, and futuristic planned cities in the Middle East.

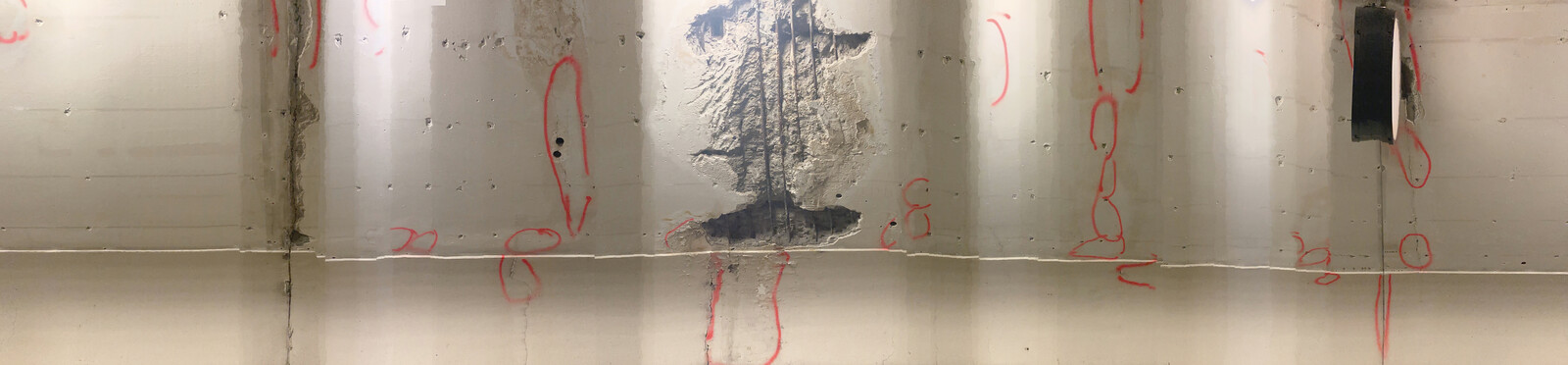

Many of the images I write about feel depopulated, but there was one image of an empty Berlin that felt full of presence to me. Repair Request (2022) by Berlin and Seoul-based artist and musician bela, is part of Data Dump Wundertüte, a collection of artworks on a USB key, which you could pick up at Spätkaufs (corner stores) around Berlin for €4.99 as part of the “Out of Scale” project. bela’s folder includes a video (a bright light with a soundtrack that feels like it was composed of found sound from the city), three phone-camera panorama photos of orange spray-painted repair requests on the ceiling of Schönleinstraße U-Bahn station in Kreuzberg, and a six-and-a-half-minute sound work, beautiful and electric. It feels like a small, romantic gesture of noticing the place around you, or an attempt to stop time in its tracks by noticing.

In the panel on “How an Image Matters,” theorist Anthony Downey discussed AI and military violence, and fleetingly described how algorithms “hallucinate”—that is, they see patterns where patterns do not exist. This is the quirk in the realism Paglen describes; or perhaps not a quirk at all. I am interested in the emotional weight of this idea. That an algorithm can malfunction the way a human does, like seeing things where they are not, or like staring out the window when your eyes should be on the screen. Why say thank you to an Alexa? It feels silly, but perhaps it’s something more: a decidedly human interaction with a digital sphere populated by algorithms that seem detached from us, yet still replicate our hallucinations and failures and crashes.

Trevor Paglen, “Machine Realism,” in I Was Raised on the Internet, ed. Omar Kholeif (Chicago: MCA Chicago, 2018), 118.