November 14, 2020–January 30, 2021

As I left Liu Shiyuan’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, I kept tripping over lines from a Robert Hass poem, “Meditation at Lagunitas”: “because there is in this world no one thing/ to which the bramble of blackberry corresponds,/ a word is elegy to what it signifies./ […] After a while I understood that,/ talking this way, everything dissolves: justice,/ pine, hair, woman, you and I.” This poem was published in 1979, when the internet as it exists today wasn’t so much as a dream, but the dissolution that Hass describes is in many respects the subject of Liu’s forensic examinations of post-internet culture. Since 2007, the Beijing-born Liu (who splits her time between China and Denmark) has devoted herself to unpacking, interrogating, even satirizing, internet semiotics. At a moment in history in which an ever-increasing percentage of the global population has been compelled online, there is a poetry to Liu’s search for meaning in a digitally atomized world.

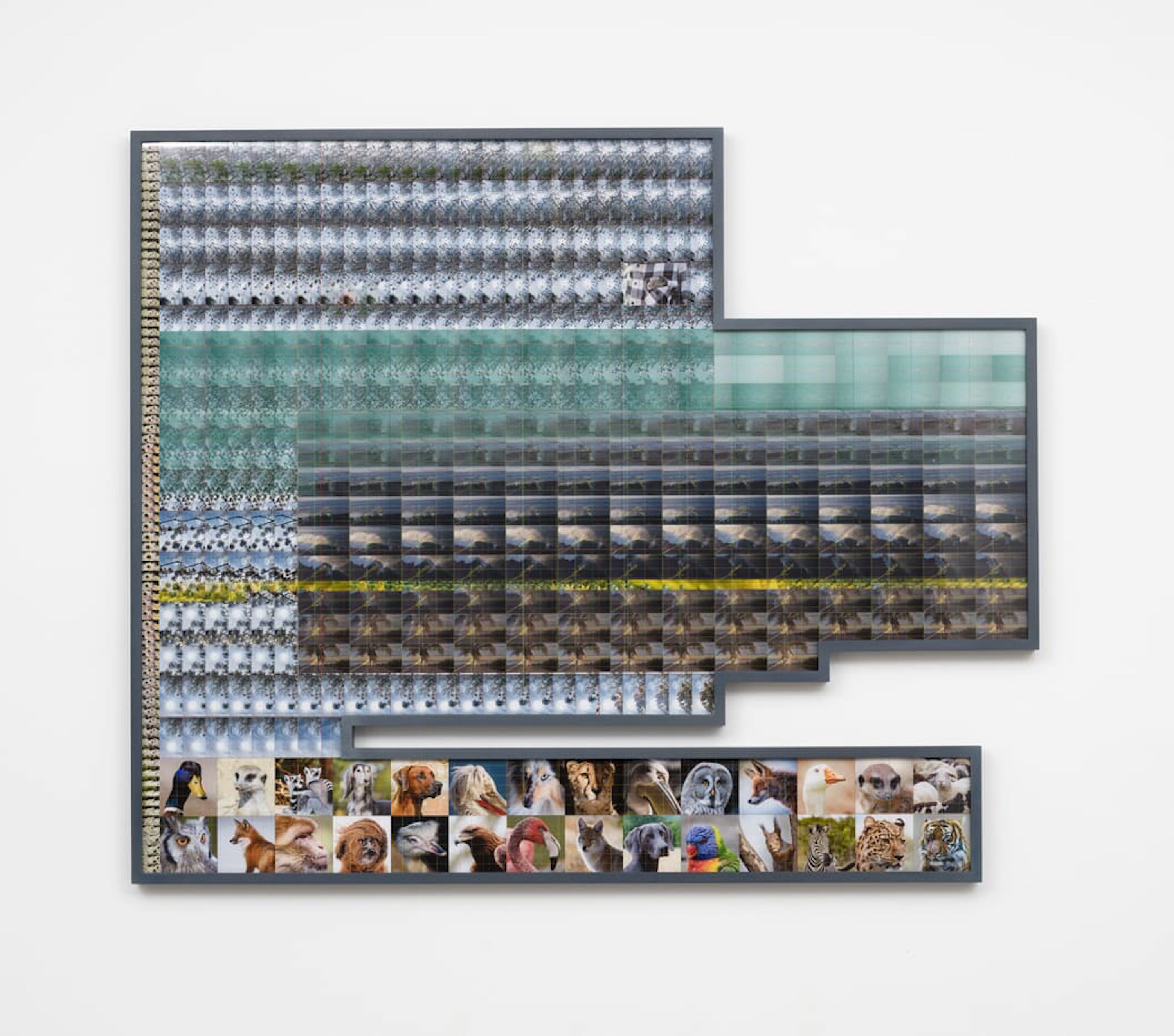

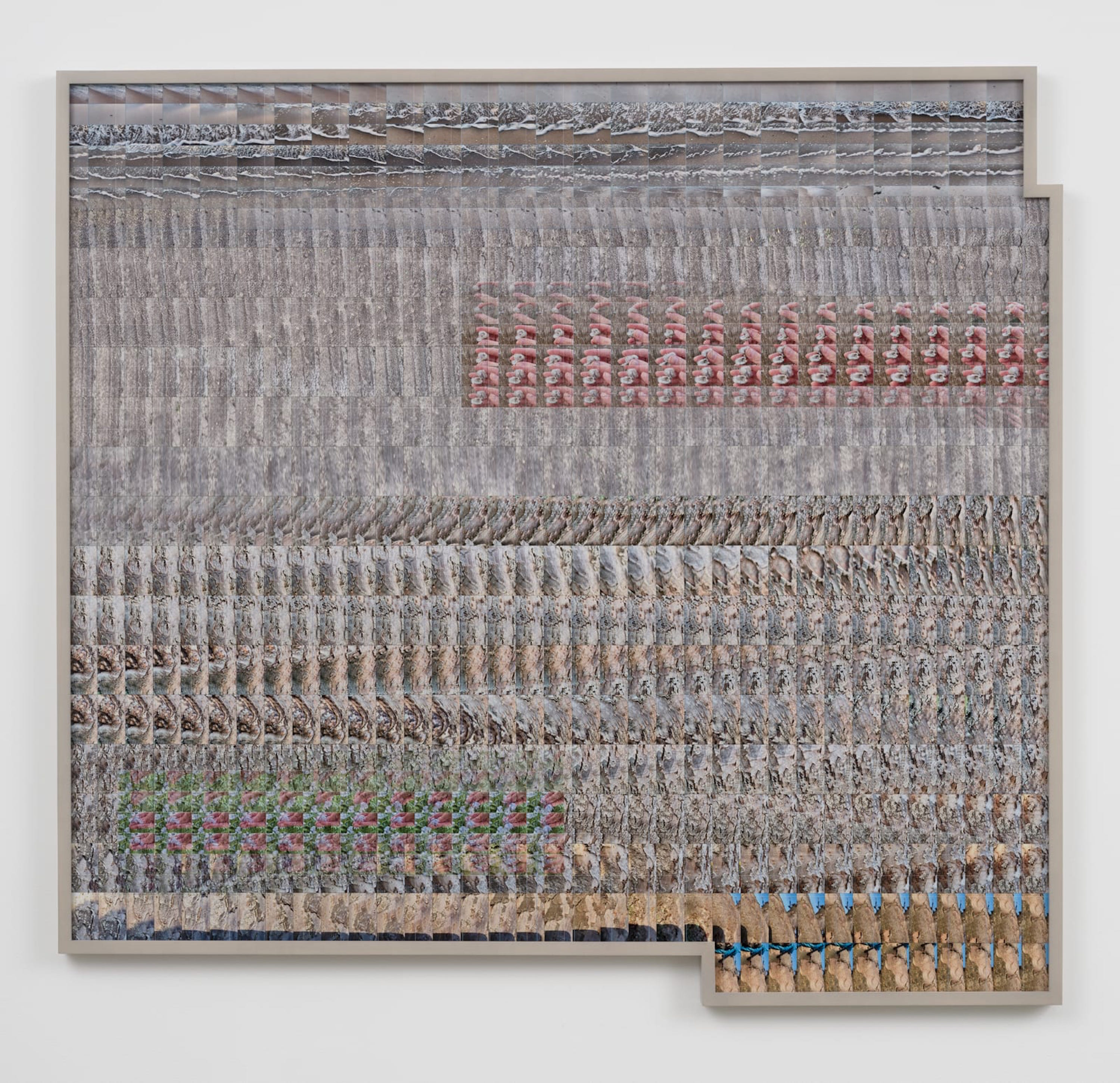

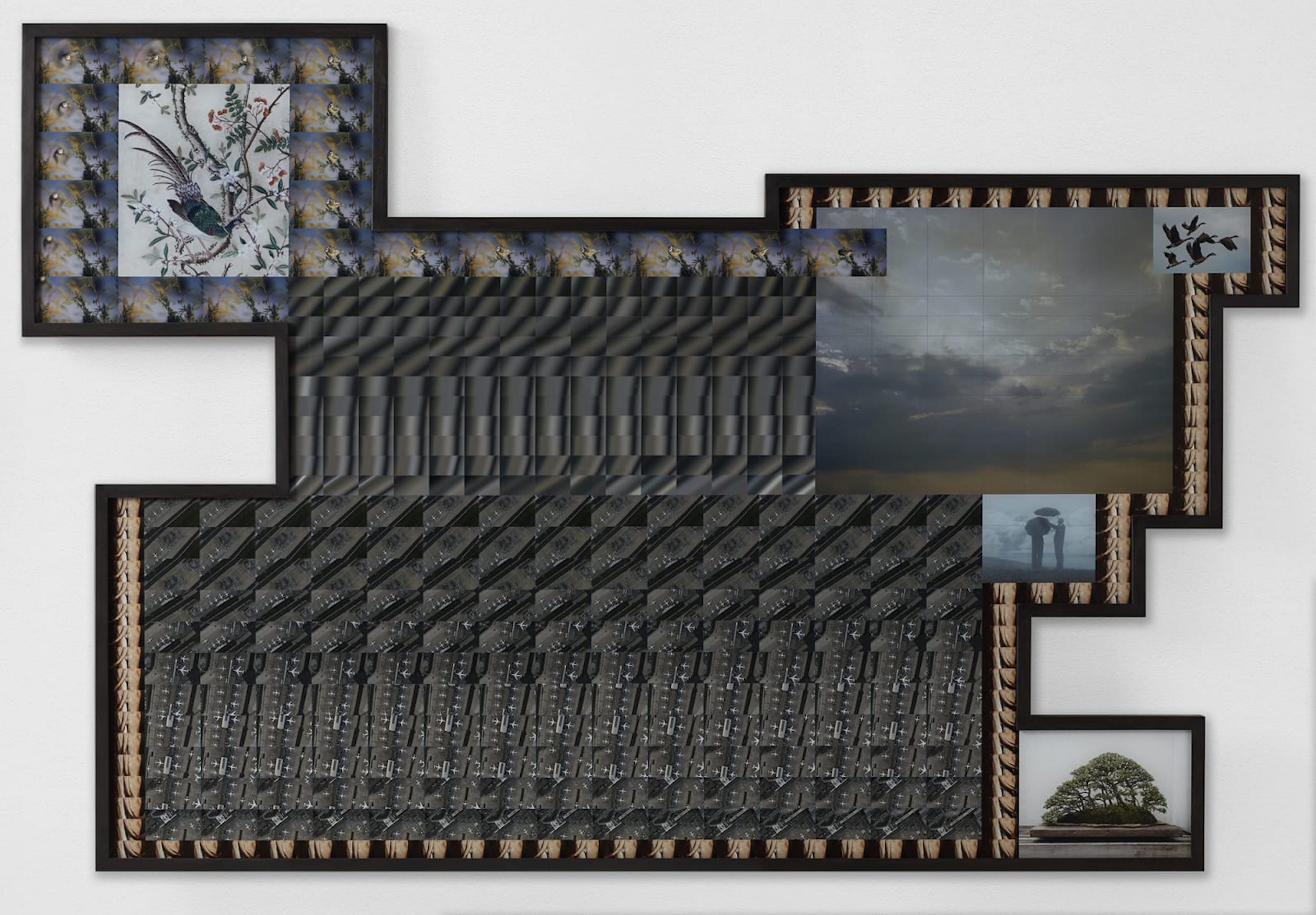

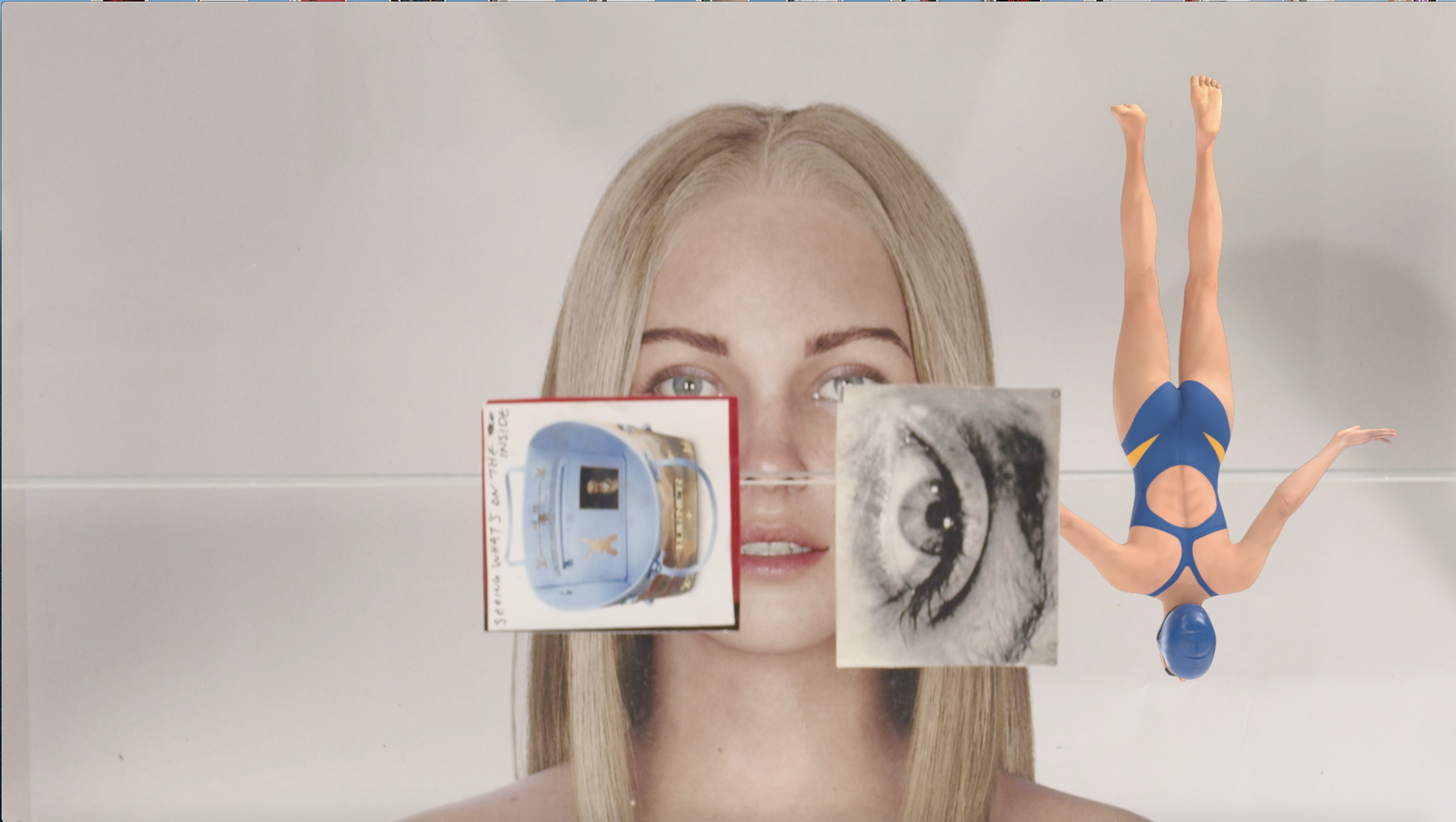

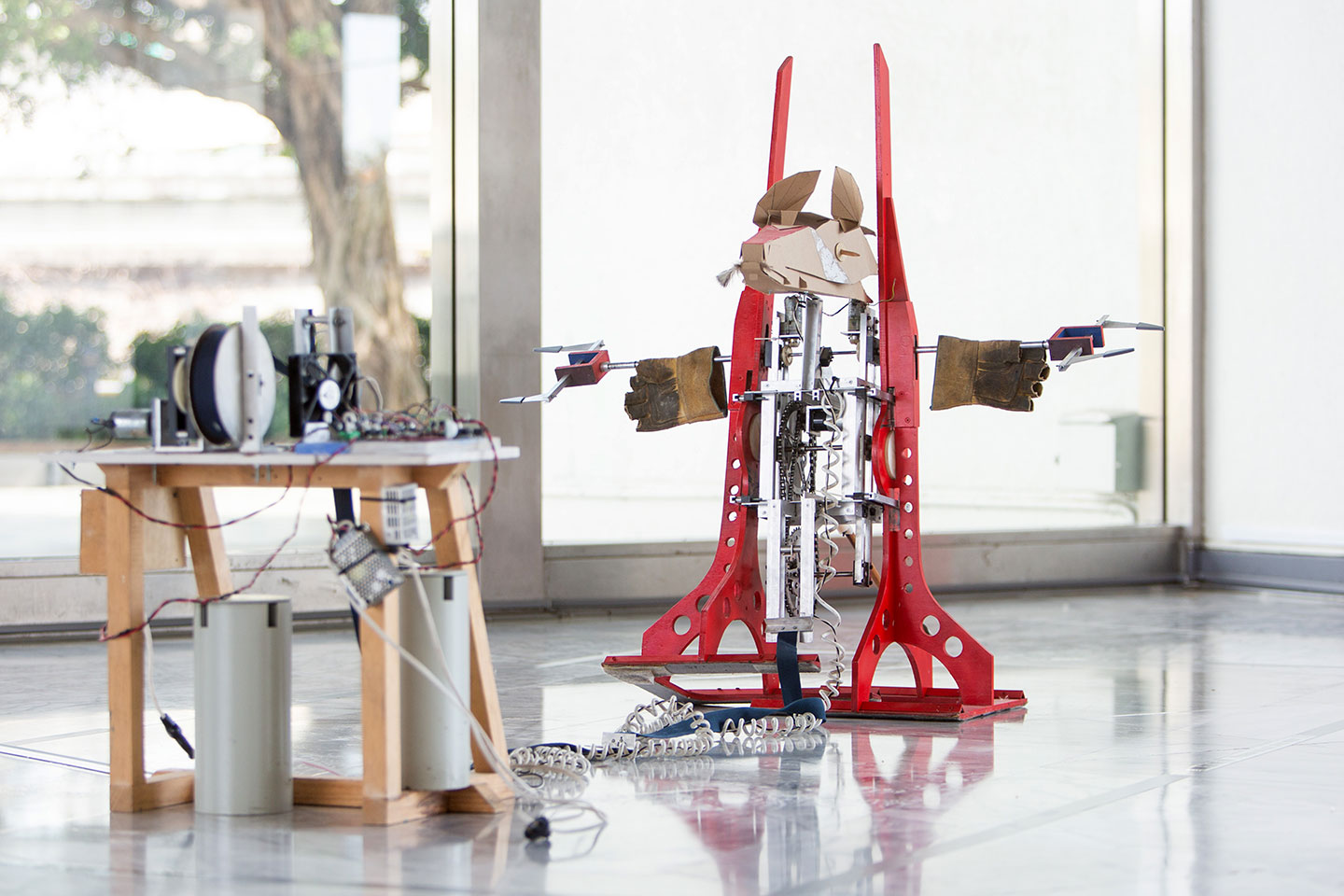

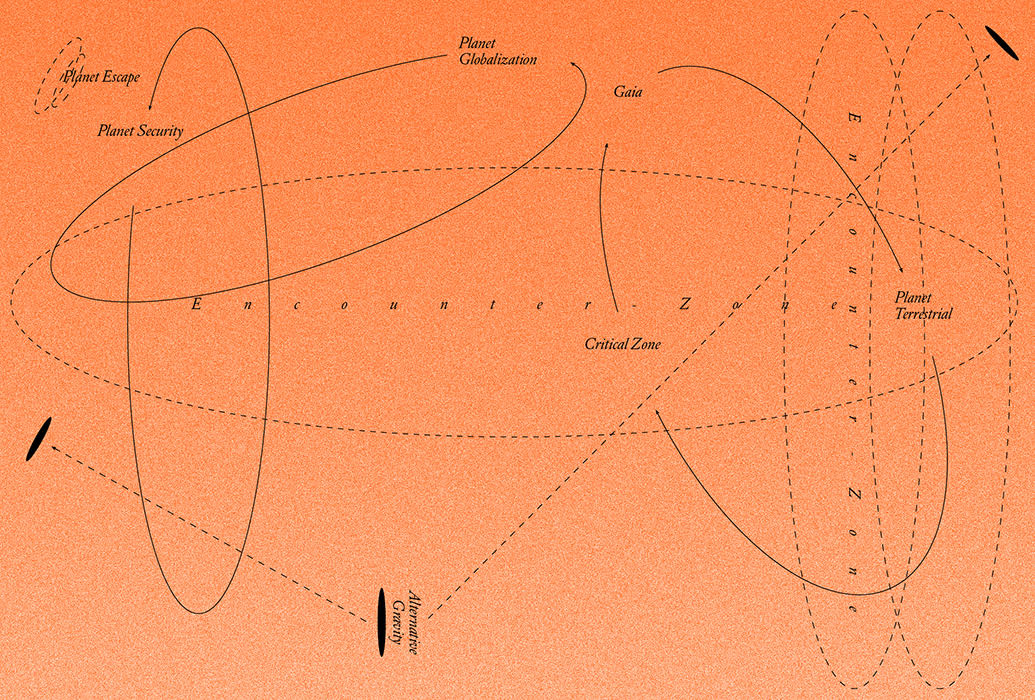

Liu’s exhibition is centered on a fictional—and purely conceptual—character named “Jord” (after whom, or what, the show is titled). Jord is both a noun and a name in Danish, translating, respectively, to “land” or “soil,” and “divine being” or “peace.” Liu is fond of Googling seemingly uniform subjects like “soil” to see what the internet will yield. She has covered similar ground before: her monumental gridded photographic installation from 2013, As Simple as Clay, comprises over 2,500 individual photographs gleaned from the internet depicting “clay.” That the word “jord,” like clay, is telluric in nature, recasts Liu as a kind of digital miner, unearthing ethereal treasure. When Liu typed “jord” into her search engine, dozens of photos appeared in which hands were seen cupping soil, framing it, containing it, appropriating it. Organic material being transposed first into a human container (hands), and then a digital one (the internet’s repository of images—a visual compost, perhaps?) appealed to Liu. The photographic works in the show are similarly contained: large, irregularly framed, rigorously organized, kaleidoscopic assemblages of images pulled from stock-image websites coupled with Liu’s own photographs and swathes of filmstrip-like shots taken from image-sharing sites. They are a testament to the constant de- and recontextualization—or transplanting, if you will—of visual information online.

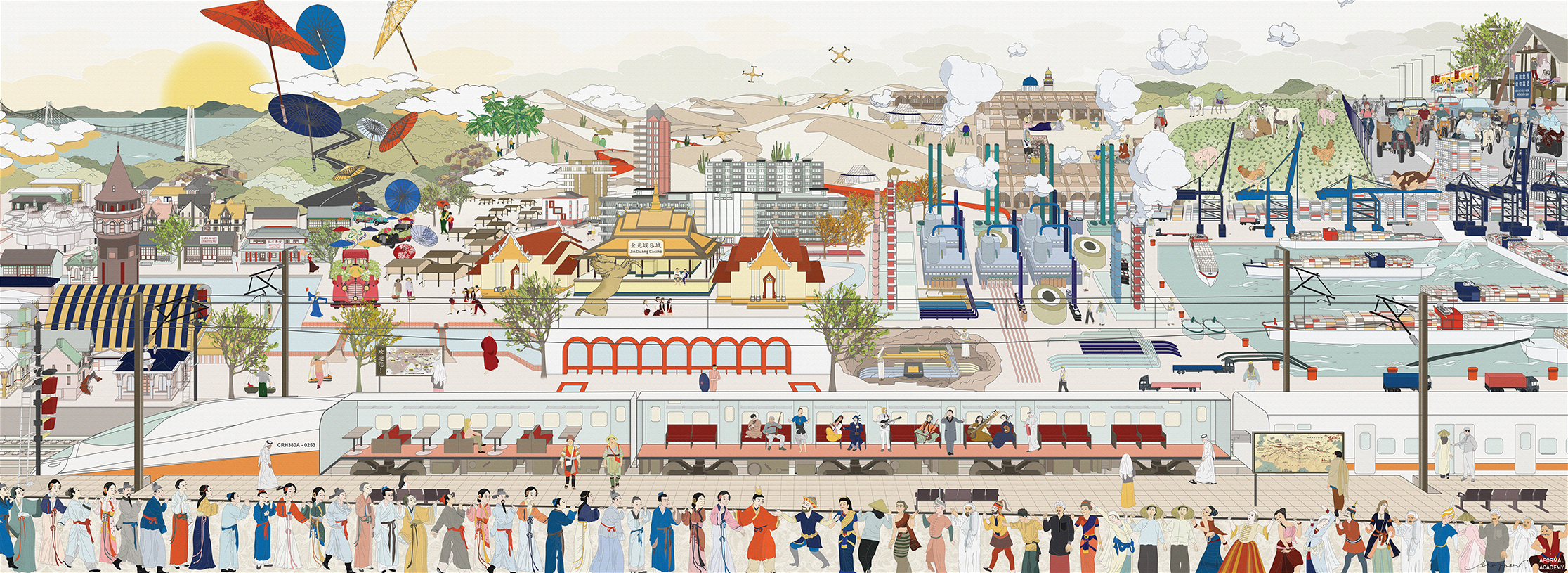

In his influential book The Closing Circle (1971), the biologist Barry Commoner outlined “Four Laws of Ecology,” the second of which states that “Everything must go somewhere”—i.e. nothing goes “away.” Essentially a reiteration of the law of physics that states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, only transformed or transferred from one form to another, it is an idea upon which Liu’s practice depends. The central work in the show, a 4k single channel video work that runs just shy of sixteen-and-a-half minutes, For the photos I didn’t take, for the stories I didn’t read (2020), traffics in this energy economy. Based on Danish author Hans Christian Andersen’s 1845 book The Little Match Seller, it is a beautiful, weird, and perplexing work. Andersen’s protagonist is an indigent girl who fails to sell any of her stock of matches on a snowy New Year’s Eve. As the night wears on, she grows increasingly desperate and begins to burn her matches to keep warm. With each successive flare she plunges fleetingly into hallucination, fantasizing about warmth and luxury, only to be consumed by hypothermia and discovered the next morning frozen to death. Though Anderson’s tale was meant to draw attention to the plight of poverty-stricken children in Europe, in 1920 the slim volume was translated into Chinese and appended to educational textbooks throughout China. During the Cultural Revolution, the government used the text to illustrate the evils of Western capitalism and justify the actions of the Communist Party.

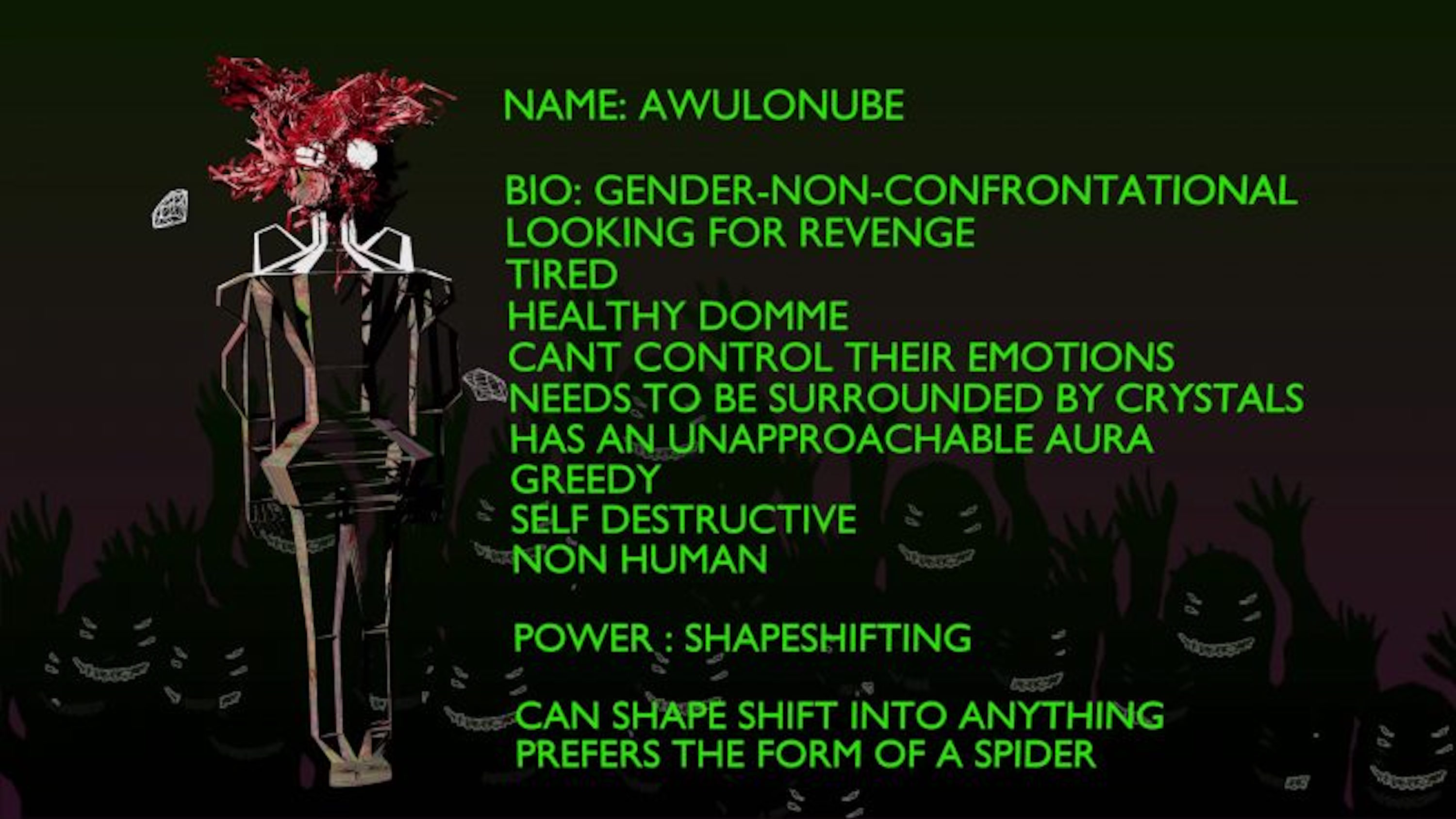

Liu’s film transcribes and illustrates the full text of The Little Match Seller (close to 1,000 words)—for every word, she assigns a Googled image, then arranges these in rebuses that run parallel to their corresponding sentences. Most notably, different images of young girls (from a diverse collection representing myriad ethnic backgrounds and socio-economic circumstances) are paired with each “she” or “her” that appears in the story. As the text scrolls by in an ironic jumble of early computer fonts reminiscent of the days of Angelfire and Geocities, larger stock images and video flood the backdrop. An ambient series of minor chords plays, drawn out in legato (the soundtrack was composed by Liu’s husband, Kristian Mondrup Nielsen), striking an elegiac tone. The nostalgic mix of appropriated and autographic materials calls to mind the work of Chris Marker—especially Sans Soleil (1983)—but, if anything, the film reads as homage not to Marker exactly, but to the restive, searching spirit that distinguished his work. Liu seems to yearn for some universal, common ground, even if the distance technology has put between us (while pedaling the illusion of proximity, of course) has alienated us in fundamental ways from our shared humanity. In 2021, maybe the image has taken over from the word, now a mere elegy to what it once signified.