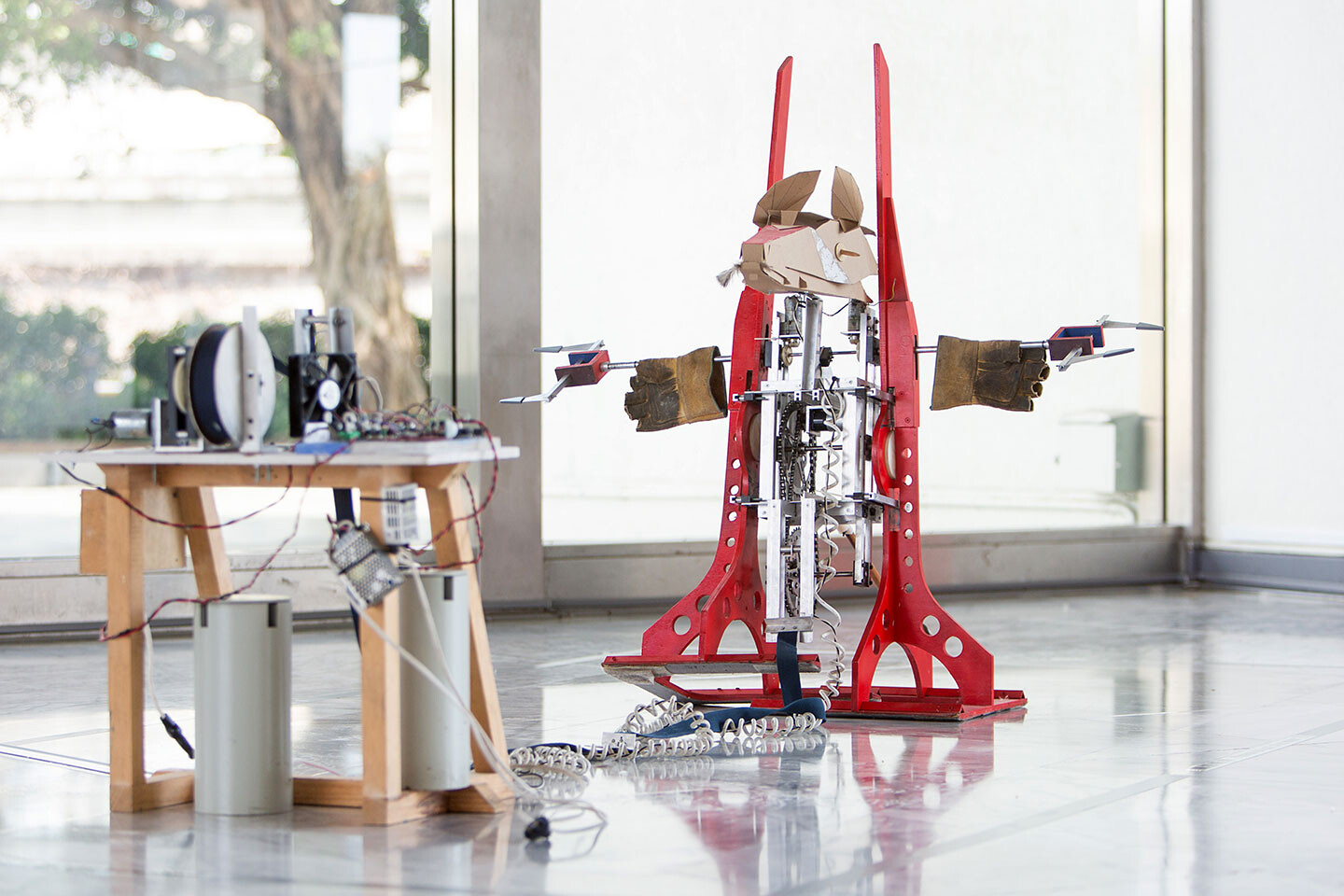

Fernando Palma Rodríguez, Soldado (red), 2001. Wooden structure, electronic circuits, sensors and software, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

What makes the present political situation so dire and different from past moments of geopolitical tension throughout history is that today the meaning of the prefix “geo-” has changed altogether. Nations are no longer fighting one another on the same geographical stage. Everything unfolds as if there were no common world to fight over, but rather a generalized fight about the very definition of what the world is made of. “Nature” is no longer the background to geopolitical conflict, but rather the very thing that is at stake. It is clear, for instance, that “climate” does not mean or signify the same things for the United States, Europe, Brazil, or China. For some states, the priority when thinking about the climate is the great risk of its catastrophic mutation; for others, any reference to the climate is a mere passing inconvenience. Against all hope, what many eco-critics are calling the “ecological turn” has not resulted in more international unification but, on the contrary, in a new round of conflicts over land, water, air, resources, and oceans.

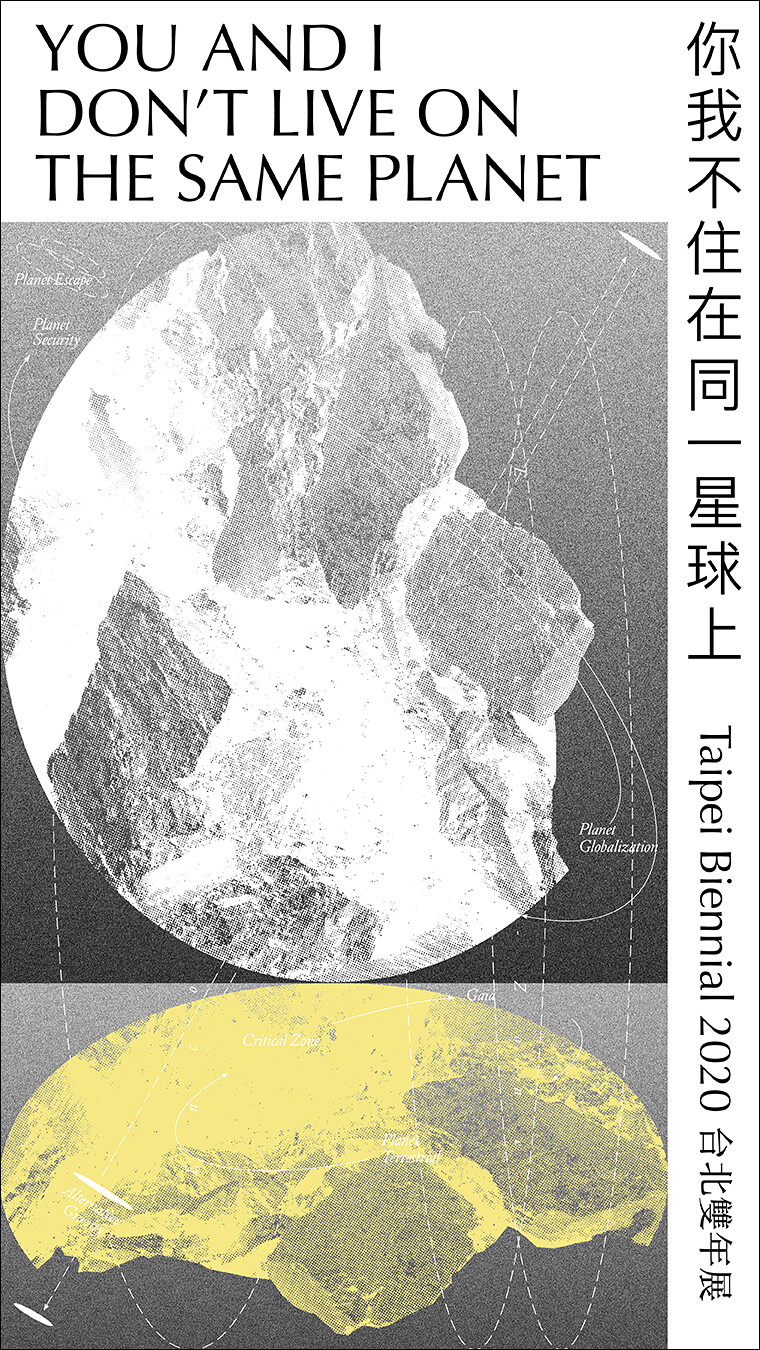

To register this shift in the definition of geopolitical conflict—a shift we have summarized with the phrase “You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet”—we propose the hypothesis that people now live on different planets. Yes, those conflicts are on a “global” or “planetary” scale, but they mobilize multiple incommensurable worlds and not simply, as in the past, different visions of the same natural world. Thus, we are witnessing a massive extension of conflicts and an extreme brutalization of politics. The “international order” is being systematically dismantled. And yet, in a strange and uncertain way, this dismantling creates a paradoxical form of unity. To be sure, it is not like former projects that imagined emancipation for all—like historical liberalism or socialism—but rather a set of new projects that aim to find ways of coping with the former natural world in novel ways.

When it comes to the vocabulary we chose for the 2020 Taipei Biennial exhibition, instead of talking about a conflict between planets we could have talked about a clash between different cosmologies, since the question comes down to different ways of articulating material reality and the social order.1 However, the advantage of using the figure of the planet over the term “cosmology” is that thinking on the scale of planets makes it possible to stage the influence that celestial bodies exert over one another, like the Moon over the tides. Astrology attempts to describe how planetary alignments influence our moods, actions, and decisions. But in this situation, it is not the influence of Pluto or Venus on our actions that is relevant, but rather different versions of the earth. Indeed, the singular image of the blue marble is now divided into different worlds which form a constellation that has nothing to do with celestial harmony. We are caught within it, where for each decision we must make, the gravitational attractions of the different configurations of earth make one’s head rotate as if on a merry-go-round. The model for describing this condition is not just some new form of dialectic (implying only two poles), but rather a configuration with a multiplicity of polarities. This is what we are trying to depict with our fictional planetarium.

Sticking with the Modern Project at all Costs: Planet Globalization

The first planet worth exploring is one we call “planet globalization.” This planet was shaped by the promises offered by modernity, when “making the world” became a central impulse. The influence of this planet is felt whenever people speak of development, progress, and increased “exchanges” between cultures.2 Though Dipesh Chakrabarty argues that the process of “world-making” began with European expansion and the Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth century, it is really during the rapid deregulation of the 1980s that this process intensified exponentially.3 In fact, this planet, planet globalization, owes much of its contemporary conception to neoliberal cosmology, which, as is well known, follows the dictums of the market’s “invisible hand” and considers the materiality of the earth as an inert object offering resources to be extracted and commodified. Of course, this phenomenon is not limited to the Anglosphere, nor to the West, as China’s opening to foreign investment in the late 1970s also plays a huge role in the intensification of the impulse for “the making of the world of the globe.”4 Even though it has produced a massive rise in inequality and in forms of neocolonialism, this planet keeps drawing people who seek unlimited growth. In this configuration, the limits of planetary boundaries are set aside, to be dealt with later. Because of the historical and contemporary influence of planet globalization, all the other planets we will explore position themselves in reaction to it.

Jonas Staal, Steve Bannon: A Propaganda Retrospective, 2018-2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

Withdrawing from the Common World and Building a Wall: Planet Security

For the many people who feel lost or betrayed by the ideals and violence of planet globalization, the general reaction is to ask for a piece of land, a border, or a haven where they can live protected from others who have also been betrayed. This is the discourse proposed by the ultranationalist movements that have taken hold in many countries all over the globe. This attraction emerges from the second planet, which we call “planet security.” One of the notable craftsmen of this movement is Steve Bannon, former chief strategist to Donald Trump. In addition to being a political consultant, Bannon directed numerous documentary films that have been influential in shaping today’s alt-right propaganda. His work in branding and articulating new images for planet security is tracked adeptly by Jonas Staal, who has presented a propaganda retrospective of Bannon’s work. Staal methodically dissects the mechanisms of ultra-right propaganda that depict a grim image of a decadence to come. According to Bannon’s films, which he himself refers to as “kinetic cinema,” the future is frighteningly beset by economic crises, Islamic fundamentalism, and the secular hedonism of cultural Marxism and the globalist elite. Only a strong leader can serve as a rampart in defense of family values, the Christian faith, military might, and of course, the US economy: all the things that Bannon defines collectively as, in Staal’s terms, “white Christian economic nationalism.”5 We find Staal’s installation Steve Bannon: A Propaganda Retrospective, 2018–2019 especially relevant because he does not offer criticism that delivers blunt blows to populist leaders, but rather explains precisely what makes this propaganda so attractive, and thus dangerous. Most notably, he does this by showing how various visual tropes recur throughout the fourteen years when these documentaries were produced, such as the figure of the storm, which heralds the “natural” and therefore inevitable approach of a decline, or the figure of the predatory animal, which is taken as a metaphor for the globalized elite attacking lonely ultra-right politicians.

The retrospective of Bannon’s work pays special attention to his “Gesamtkunstwerk”: the Biosphere 2 Earth Systems Science Research Facility in Oracle, Arizona, of which he became CEO in 1993 (a model of this project is also shown in the biennial.) Inside this covered park of more than one hectare was the world’s largest artificial ecosystem, designed with the aim of testing the survival capabilities of humans, flora, and fauna in an enclosed space that could be replicated, integral to Bannon’s conception of a future of interplanetary colonization. The project was a failure; for one, oxygen levels dropped so low that breathable air had to be introduced from outside.6 The project was also a financial disaster. Bannon’s solution was to turn to Columbia University for extra funding, but with a significant twist: now Biosphere 2 would no longer seek to explore the possibilities of extraterrestrial colonization. The site would instead be used as a space to conduct climate change experiments, as Staal describes. Taking this fact into consideration, Bannon’s role in the Trump administration’s 2017 abandonment of the Paris Agreement is yet more surprising. It clearly demonstrates that those like Bannon who are attracted by the pull of planet security are not necessarily ignorant or in denial of these climate challenges. As they feel the ground slip away under their feet, and as they see that there is no hope of creating the conditions to inhabit Mars, the choice they make is to withdraw from the common world behind economic and ethnic barriers, engineering what Staal refers to as Bannon’s “alt-right biosphere.”7

Femke Herregraven, Corrupted Air–Act VI, 2019. Mixed media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

If Earth Is Doomed, Let’s Get Out of Here: Planet Escape

The third planet that we propose to explore is “planet escape.” It concerns a small number of privileged people who are way past denying climate catastrophe, and for whom it has become imperative to either exit from their body via a transhumanist project, or leave the earth by colonizing Mars. Alternatively, if it takes too long to develop either of these high-tech extravaganzas, they may opt for a more a familiar brick-and-mortar solution by building bunkers deep underground, in places that might be less affected by climate collapse. The pull of this planet escape is visible, for instance, in the work of the artist Femke Herregraven, whose installation Corrupted Air—Act VI invites spectators into one of these survivalist bunkers to explore the imaginary of a “panic room,” a small living space used in the event of catastrophe. As the installation’s doors open, the visitor enters a room with no windows, lit with blue neon light, filled with metallic structures that span the space, equipped with basic furniture such as two beds kept under plastic sheets to protect against moisture, water supplies, and books such as Paul Virilio’s Bunker Archeology (1975). The space remains mostly uninhabited, except for the avatars of three strange creatures: an elephant bird, a trilobite, and a lizard, all extinct, are displayed on a screen. These animals have come back to “life” thanks to highly precise scanned digital models. As they engage in a discussion written by the artist, they continually mention a character who shines forth in his absence: the “Last Man,” who is the owner of the space.8 He is to be understood as a sort of prophetic figure, who nevertheless brings no salvation: “When he arrives, I’ll be even more bored” says the digital trilobite who wonders what the point is of living on a “lonely planet.”9

MILLIØNS (Zeina Koreitem & John May) with Kiel Moe and Peter Osborne, The Ghost Acres of Architecture, 2020. Installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Artist and Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

Looking for a Way to Land: The Terrestrial Planet

For those who have understood that the modernizing projects of planet globalization can go nowhere since it would take the resources of many earths for the entire planet to live the American way of life; that planet security is unrealistic since the planets are inextricably intertwined; and that planet escape is only a pipe dream, and a depressing one at that, where are they to turn? What planet can they go to? Many different names could serve to identify the inhabitable place we are searching for, but in the context of this essay we call it “the terrestrial planet.”

The terrestrial planet is at a disadvantage compared to those mentioned above for many reasons: its contours, aesthetic, and modes of inspiration are a lot less clear when compared to the crisply packaged and marketed planets of globalization and escape, and it lacks the well-orchestrated propaganda mechanism of planet security. The terrestrial planet attempts to create a cosmology which, per John Tresch, still lacks a “cosmogram”: a set of representations of what it could mean to achieve prosperity within the earth’s own limited planetary scale and resources.10

To develop the contours of the terrestrial approach, the first step is to exchange the canonical image of the earth—the iconic blue marble, stable, seen from far away, symbolizing an ideal of global governance—for something more realistic and appropriate for the contemporary moment. Relying on global governance to solve the problems caused by ecological change—the ultimate ideal of planet globalization—is futile. Recent examples of division in the US, or Europe’s inability to federate on its own modest scale, send a clear message to all those who still hold out hope for intercontinental unity.

Instead of the image of the globe, we propose diving into representations of what scientists refer to as the “critical zone”: the upper near-surface layer of the earth. If the planet were an orange, the critical zone (CZ) would be its skin. It is a thin layer where water, soil, rocks, plants, and animals interact to create the necessary conditions for life. This space is extremely thin, a few kilometers above our heads and a few under our feet, which is small compared to the earth’s 12,700-kilometer diameter. And yet it is within this envelope that life takes place.11

Studying the CZ is not at the scale of the full globe, like earth systems science models, for example. Rather, the CZ is studied through a set of delimited observatories where scientists from different disciplinary backgrounds try to better understand how various processes interact with one another, on that zoomed-in scale. Because the CZ is variable and heterogeneous, scientists try to compare phenomena seen from one observatory to the next, attempting to build a better understanding of this thin layer within which all life-forms we know reside.

As geochemist Jérôme Gaillardet would say, to understand how the CZ functions at the scale of the planet, it would be necessary to have as many observatories as we have hospitals.12 Clearly, the earth is far from benefiting from a network of such sites, but there is an important observatory located in Taiwan, in the Taroko Gorge, that could serve as a perfect example of such an observatory. The artist Yuhsin Su was able to follow two groups of scientists to a site in Taroko that was selected because geological dynamics are particularly active there.13 Her work Frame of Reference I & II investigates the position of the observer and of their instruments inside these open-air observatories, adopting what she calls a view from “within.” The artist draws on two different methodologies—those of Leonhard Euler and Joseph-Louis Lagrange—to explore connections between the observer and their “object” of study. These two eighteenth-century mathematicians defined different “frames of reference” that are still used today by critical-zone scientists to conduct observations. In a Eulerian frame of reference, the position of the observer is fixed in space, which allows one to see what happens from a single perspective. In a Lagrangian framework, however, the observer moves with their object and is, therefore, relative.14

Su Yu-Hsin, still image from Frame of Reference, 2020. Video installation, dimensions variable. Frame of Reference I was produced in cooperation with the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe and GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences Geomorphology. Image source: GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Taroko Project Database, NCTU Disaster Prevention, and Water Environment Research Center.

The structure of Su’s video switches between Eulerian and Lagrangian frames of reference, alternating images taken from a fixed viewpoint (a GoPro camera placed underwater in a river, and a camera positioned on a hydrometric station near the riverbank) with images taken from a moving viewpoint (a drone and a handheld camera). The video installation, with its sensory style, bypasses a stable “subject/object relationship” thanks to its immersive setup. The tilted screens laid out around visitors do not put them “in front” of the work but “encapsulate” them within it. This echoes the position of the observer inside the CZ who is always “within” the skin of the earth, within the flesh of the world, and therefore cannot escape, nor withdraw, from this terrestrial position.

It is in the ability of this planet to register the diversity of ways of inhabiting the earth that it should be judged. This is why we are so interested in the alternative “observatories” set up by indigenous groups in critical zones that have been massively disturbed. The works of Aruwai Kaumakan, who is from the Paiwan tribe in southern Taiwan, offer a typical case. Her village was hit by a particularly violent typhoon in 2009, forcing its inhabitants to relocate to the current land of the Rinari tribe. She offers an interesting way of approaching questions of dwelling and inhabiting after resettlement. She creates sculptures with wool and fabric, weaving together organic or vegetal forms using “Lemikalik,” a Paiwan technique that involves weaving in concentric circles. Through this technique she intertwines memories of tribal nobility to form a place for constant conversation and connection. She used to create jewelry, but she felt the need to “upscale” to larger pieces after the typhoon, allowing her to collaborate with others in the weaving process, literally recreating a social fabric. One should resist using the term “resilience” to characterize her practice, as it can indulge in forms of conservatism, accepting a situation rather than mobilizing against the problem.15 Thinking about dwelling and inhabiting is especially important given that there will be more climate refugees in the comings years, driven to migrate by climate events like the typhoons that displaced the Paiwan.

The terrestrial planet is marked by a difficult problem: it seems that nothing is at the right scale any longer. The heart of the discoveries of James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis is that the earth’s surface (the CZ) is a complex, self-regulating system in which every single element—rocks, gases, minerals, water, atmosphere, soil—has been modified by the actions of life-forms, notably bacteria. But the key concept from this model is that even large-scale changes are the result of entities and contexts that are small-scale. The challenge is to resist the temptation to remain within the opposition between “global” and local phenomena. We must also address the concept of locality without getting stuck within the confines of the local. There is a need to resituate the territories from which we draw necessary resources but which we don’t see—a need to situate the “ghost acres” (to use Kenneth Pomeranz’s expression) that are necessary for feeding our daily lives.16 This is especially visible in a work proposed for the biennial by the architecture collective Milliøns with Kiel Mo and Peter Osborne.17 In The Ghost Acres of Architecture, they take up the complex task of drawing what such resituated territories could look like. Since it would be impossible to do this at the scale of a full city, they start with Mies Van der Rohe’s famous 1958 Seagram Building in New York City, visualizing data from the first moment of extracting the materials for its construction through its contemporary operation. Milliøns analyzes the immense territorial reach of these processes—the minerals, the energy, the interactions with the earth’s crust. Architecture is an ideal site to measure up the conflicts between globalization and what could be called “terrestrialization.”

Of course, the 2020 Taipei Biennial is also caught between these attractors. Typically globalized in terms of its theme and resource consumption, it has addressed different topics since 1984: the monsters of modernity (Franke, 2012), the question of the Anthropocene (Bourriaud, 2014), and the museum as an ecosystem (WU, Manacorda, 2018). If we speak in terms of the material production of an exhibition and not only in terms of its themes, it is easy to be “global” with artists from twenty-seven countries, and it remains a real challenge to get an exhibition like this one to land on a terrestrial planet. For example, in their work Arts of Coming Down to Earth, Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro, Ming-Jiun Tsai, and Margaret Shiu tried to find ways to see how institutions could “expand their maintenance practices beyond the object, to non-human collectives.”18 This involved an audit of the CO2 consumption of the biennial, as well as allowing a large area of degraded land in Taiwan to regenerate, focusing on biodiverse reforestation and protection. The ethos of their project involved neither greenwashing nor the proposal of an easy solution to a complicated problem. At the very least we have to admit that the Covid-19 pandemic had the merit of removing one of the contradictions of attracting globalized crowds from the world of art and cultural tourism!

Diplomacy: Onwards from the Fictional Planetarium

As has been suggested throughout this essay, the hypothesis on which we rely is the following: people tend to accept representations of the world that make it possible to live and act within it. When it was understood that the earth was round in the sixteenth century, a way of “shaping” the world was developed through circulation, trade, and imperialism. With the earth as a globe—that is to say, as an inert object—few possibilities are available to understand ecological problems, since this representation of the blue planet as a giant billiard ball simply invisibilizes the deregulation of the biosphere, as well as all the alternative cosmologies that never fit within the globalized ideal in the first place. Thus, it is important to identify some of these different ways of “world-making” and how they differ from one another, as well as to acknowledge that there are many other planets that can be added to this fictional planetarium.

So, where do we direct ourselves once this position of division is fully assumed, once our colonial history has damaged the ideal of universalism, once we find ourselves in a fragile situation that is being exploited to serve populist agendas? The present imperative is not simply to foster a discussion among a multiplicity of perspectives, since this would inevitably fall back to older models of universalism—reconciling multiple visions of the same natural world. The aim here is to explore alternative procedures that still aim at some sort of settlement, but only after having fully accepted that divisions go much deeper than those anticipated by old universalist visions. Or perhaps the aim is to show why this is impossible and draw political and ethical conclusions from this dilemma.

Since we lack a common world, it is crucial that we imagine different procedures that will at least explain why it is impossible to simply “sit at the same table.” What are peace and war when dissension runs this deep? If you and I don’t live on “the same planet,” it is crucially important to explore alternative modes of encounter between these worlds, to avoid destruction. It is because people are caught between the wishful thinking of planetary governance, the brutalization of politics, and the dismantling of the international order that we appeal to the notion of diplomacy. Of course, one cannot ignore that in the current situation, diplomacy may seem too weak. To give an example: an associate of Steve Bannon contacted a museum showing Jonas Staal’s retrospective on the propagandist, and asked if Staal would “debate” Bannon. Staal declined, emphasizing that while he felt it was essential to develop propaganda literacy and build counterpower, he refused to give a platform to an alt-right propagandist who promotes planet security. This attitude might also be understandable when looking at the size of the communication networks that Bannon owns, which are, unfortunately, much larger than Staal’s. But one should not confuse diplomacy with polite discussion. Diplomacy offers a compelling proposition: First because it brings together procedures and techniques used before or after wars and conflicts, which is a fitting description of the current situation. Second, since it takes place in the absence of an overarching authority, diplomacy can be particularly useful at a time when the “international order” has demonstrated its fragility after four years of Trumpism. Third, although it certainly is not immune to asymmetrical imbalances of power, diplomacy offers parties the possibility of negotiating to remain engaged so long as they remain alive. Although we must admit that it is a serious possibility, the pull of planets globalization, security, and escape have not yet sucked the terrestrial planet into a black hole, with gravity so strong that not even a ray of light can escape.

If the issues raised by the new climate regime are divisive, the goal is neither to remain so forever nor to unify too quickly, for fear of falling back into the trap we described earlier—namely, that moralizing arguments paralyze the effort to build a politics that knows how to identify the concrete interests that should be defended. Therefore, we argue that “new diplomatic encounters” are necessary. Imagining how to even engage in such encounters when different people do not even share the same ground and the same atmosphere remains a difficult question, which we try to address in our curation of the 2020 Taipei Biennial and in this issue of e-flux journal.

See the exhibition pamphlet You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet, authored by Martin Guinard and Bruno Latour for the 2020 Taipei Biennial.

This is also the planet that has most directly influenced the conception of the biennial and its ideal of “mondialité” (worldness), given that the Taipei Biennial was established in 1984 with the stated mission of promoting international exhibitions.

See Dipesh Chakrabarty’s contribution to this issue, “World-Making, ‘Mass’ Poverty, and the Problem of Scale.”

Chakrabarty, “World-Making, ‘Mass’ Poverty, and the Problem of Scale.”

Jonas Staal, “Propaganda (Art) Struggle,” e-flux journal, no. 94 (October 2018) →.

Bettina Korintenberg, “Life in a Bubble: The Failure of Biosphere 2 as a Total System,” in Critical Zones, ed. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (MIT Press, 2020), 185.

Jonas Staal, personal conversation with the authors.

See the recent essay by Simon Sheikh that explores another image of this last man: “It’s After the End of the World: A Zombie Heaven?” e-flux journal, no. 113 (November 2020) →.

See the website for the 2020 Taipei Biennial →.

See John Tresch’s contribution to this issue, “Cosmic Terrains (of the Sun King, Son of Heaven, and Sovereign of the Seas).”

See Bruno Latour, “Seven Objections Against Landing on Earth,” in Critical Zones.

Jérôme Gaillardet, personal conversation with the authors.

We thank the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, especially Niels Hovius and Jens Turowski, and the NCTU Disaster Prevention and Water Environment Research Center in Wuhe and Wulu for their help in realizing this project.

Bastian E. Rapp, “Conservation of Mass: The Continuity Equation,” chap. 10 in Microfluidics: Modelling, Mechanics and Mathematics (Elsvier, 2016), 265–77.

On the topic of “refusing” resilience, see the section “Nous ne voulons plus être appelés résilients” in Matthieu Duperrex, “Arcadies altérées, territoires de l’enquête et vocation de l’art en Anthropocène” (PhD diss., Toulouse University, 2018), 275–80.

Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Milliøns is Zeina Koreitem and John May.

See the website for the 2020 Taipei Biennial →.