A large installation of T-shirts stretched across metal wall studs anchors MoMA PS1’s 2021 iteration of “Greater New York.” The T-shirts—by the collective Shanzhai Lyric—are the bearers of mistranslations (“Revoltig/No!/Save the Queen”), misspellings (“La Vieen Rose”), juxtapositions that make little to no sense (“LV/Louis Vuitton/Challenger Races for the Americas Cop/For the Americas Cop”), or free-floating phrases that violate the semiotics of communicative clothing (“I’ll be back!/I’ll be back!”). Shanzhai is the transliteration of a Chinese word for both “mountain hamlet” and “counterfeit.” The shanzai T-shirts, collected since 2015 from Hong Kong to New York City, are part of an ongoing project—or poem—that urges us to think about translation, trade networks, the exchange value that is increased by the designation “real,” and, as the artists note in the wall-text, “how deeply we can be moved by apparent non-sense, how it actually seems to describe with poetic precision, the experience of living in an utterly nonsensical world.”

Incomplete Poem (2015–ongoing) might serve as a useful cipher for a large and, one could argue, unavoidably chaotic exhibition. “Greater New York” is staged every five years. It is what it sounds like: an exhibition meant to give viewers a sense of what artists are making across the city’s five boroughs in and out of gallery systems. Setting aside the nominal geographic restraint, the curatorial mandate is wide open. And so meaning generated from the juxtaposition of playful and obscure phrases printed on objects that could easily be read as metonyms for the global movement of bodies into a city that is itself a metonym for immigration might be a pleasantly didactic way to open the show.

Featuring 47 artists (far fewer than in previous years) spread out over four floors, the 2021 iteration of “Greater New York” was curated by by Ruba Katrib along with Serubiri Moses, Kate Fowle, and Inéz Katzenstein. According to the press release and primary wall text, the show “opens up geographic and historical boundaries” but still attends to “strategies of the local,” which means, in practice, that anyone with an occasional or casual relationship to New York City can be included in the show. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this. Indeed, New York City (more so than most places) does not exist as an entity independent of trade networks, capital flows, and a global population. Unfortunately, these claims concerning open borders (I’m not sure “boundaries” can be “opened,” grammatically speaking) may be read not as a good faith effort at internationalism but a lazy repetition of the latest round of art-critical pieties.

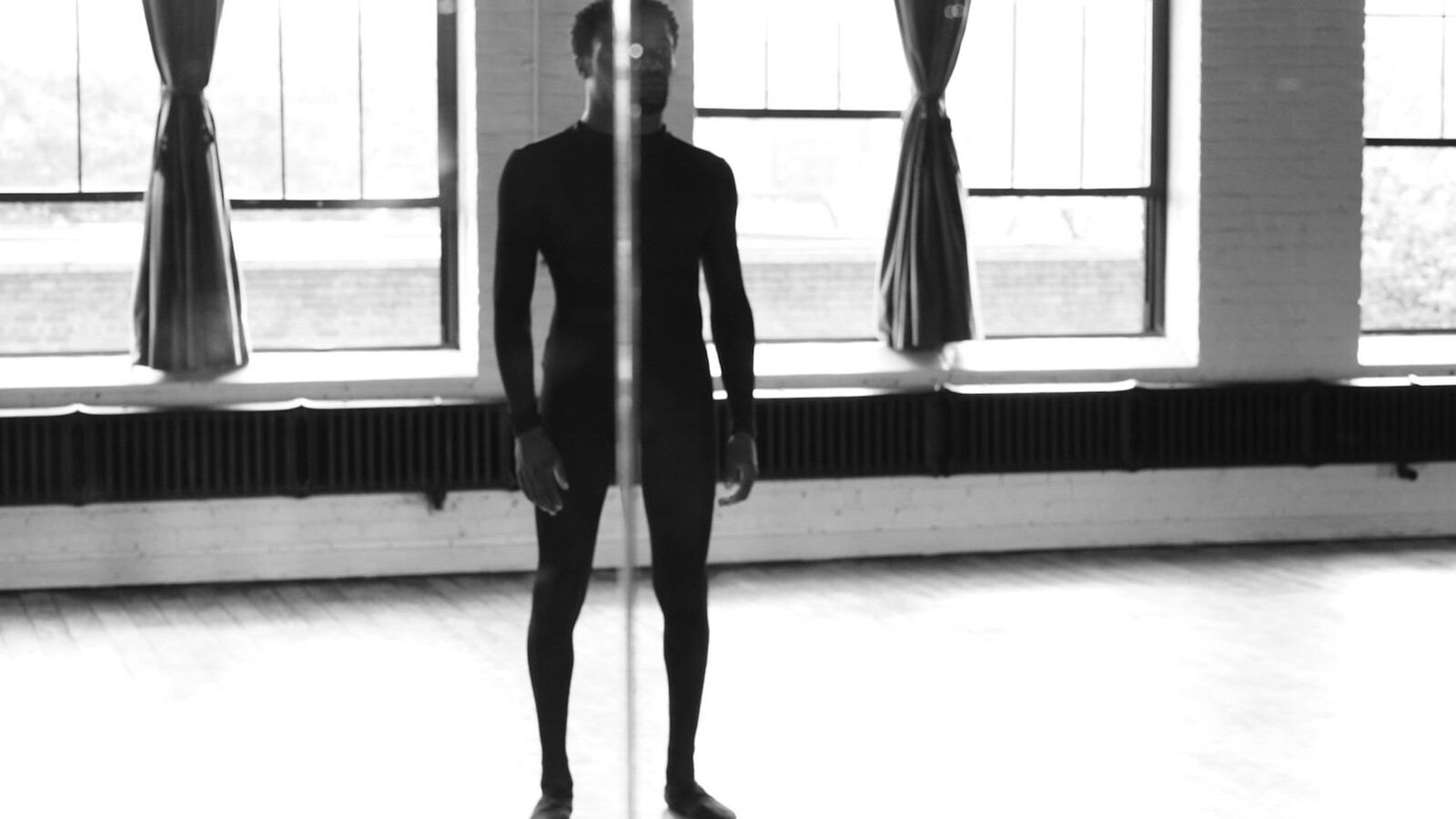

There are many pieces that make the trip to Long Island City worth the trouble. Steffani Jemison’s Similitude (2019) deploys a doubled gaze and a noticeably flawed reflective surface as the setting for a movement-based work that aesthetically recalls an earlier era of (feminist) performance. These formal aspects create a certain distance from the present that allows its very relevant content to breathe. The subject here is a black male. Over the duration of the film he strikes poses, observes them objectified in the mirror, revises them according to a logic at once apparent and inaccessible to the spectator, changes place. As the camera swivels from mime to mirror, we alternately watch someone who is trained in controlled gestures and watch them watching an image of themselves. It’s a powerful piece—legibly political, but literally and formally muted (the mime is silent, the camera movements simple and repetitious, the soundtrack assertively minimalist). Here is an examination of internalized regimes of control, performative representations of the self, the double-consciousness produced by America’s color line, and, given the current political context, the defensive use of hyper-conscious bodily movement demanded of certain identities. But the work is also a film, a dance, a playful meditation on self-reflection. It is continuous with an aesthetic tradition that extends beyond its immediate time and place.

Three paintings by Paulina Peavy, which look as if someone has spliced together the brains of Tamara de Lempicka and Hilma af Klint, are a visual decadence for which I will forever be grateful. But I’m not sure what they are doing in the show, nor why they were relegated to a side gallery in range of Diane Burns reciting her “Alphabet City Serenade” (1989; also fantastic, but inscrutably positioned). Alan Michelson’s Midden (2021)—color video of trash barges projected onto a pile of oyster shells or “midden heap”—is a comment on human impacts on the environment over time that simultaneously criticizes the amount of trash produced by contemporary consumers and undermines Rousseauian fantasies of living at one with nature. It is also a surprising and pleasurable use of surface texture to alter a projected image. The large, colorful pigment prints by Avijit Halder give us a body improbably posed in decidedly unexotic domestic spaces transformed into sites of frenetic performance by what appears to be an excess of sari cloth that has nearly filled the frame and taken on a sculptural solidity. The amount of movement captured here is astounding.

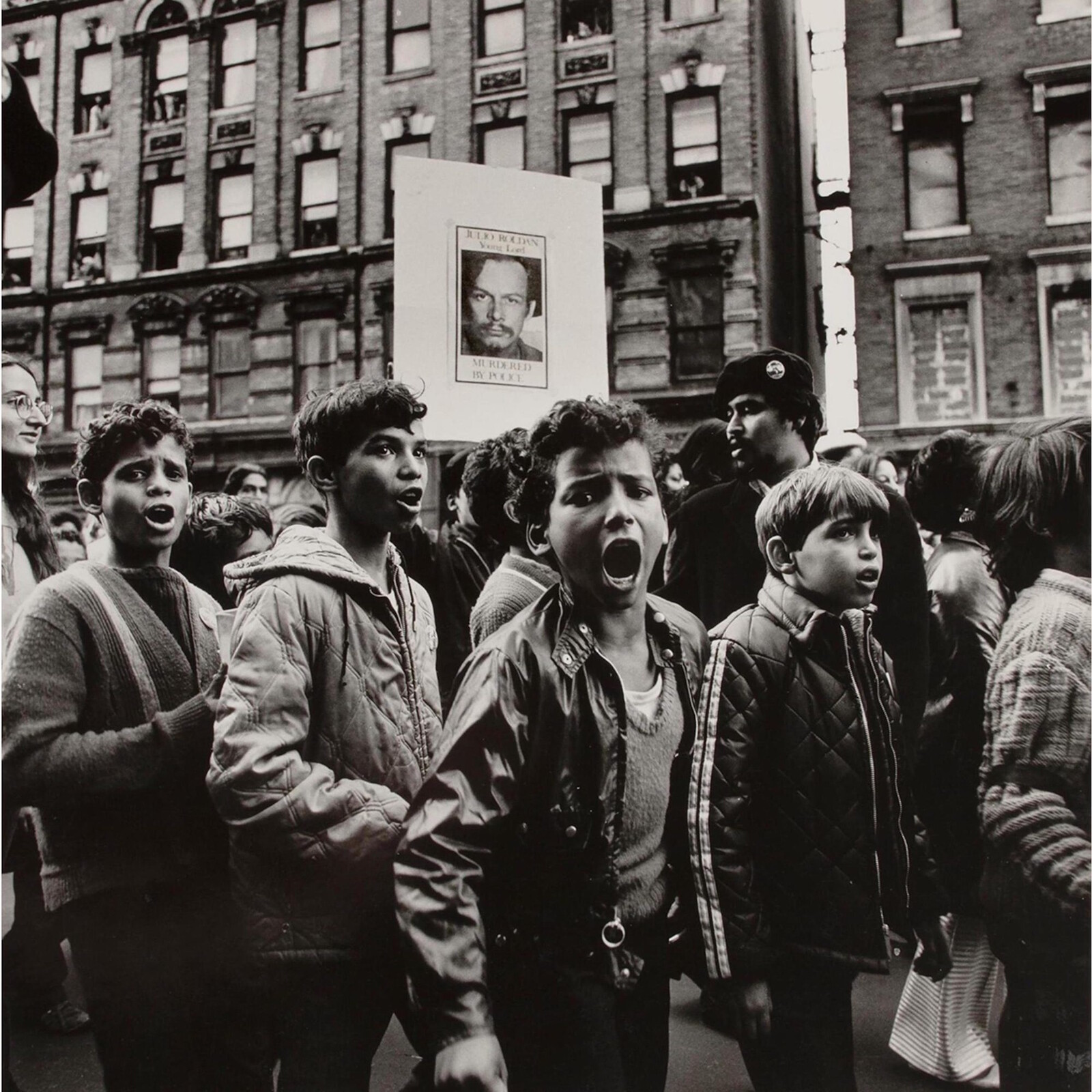

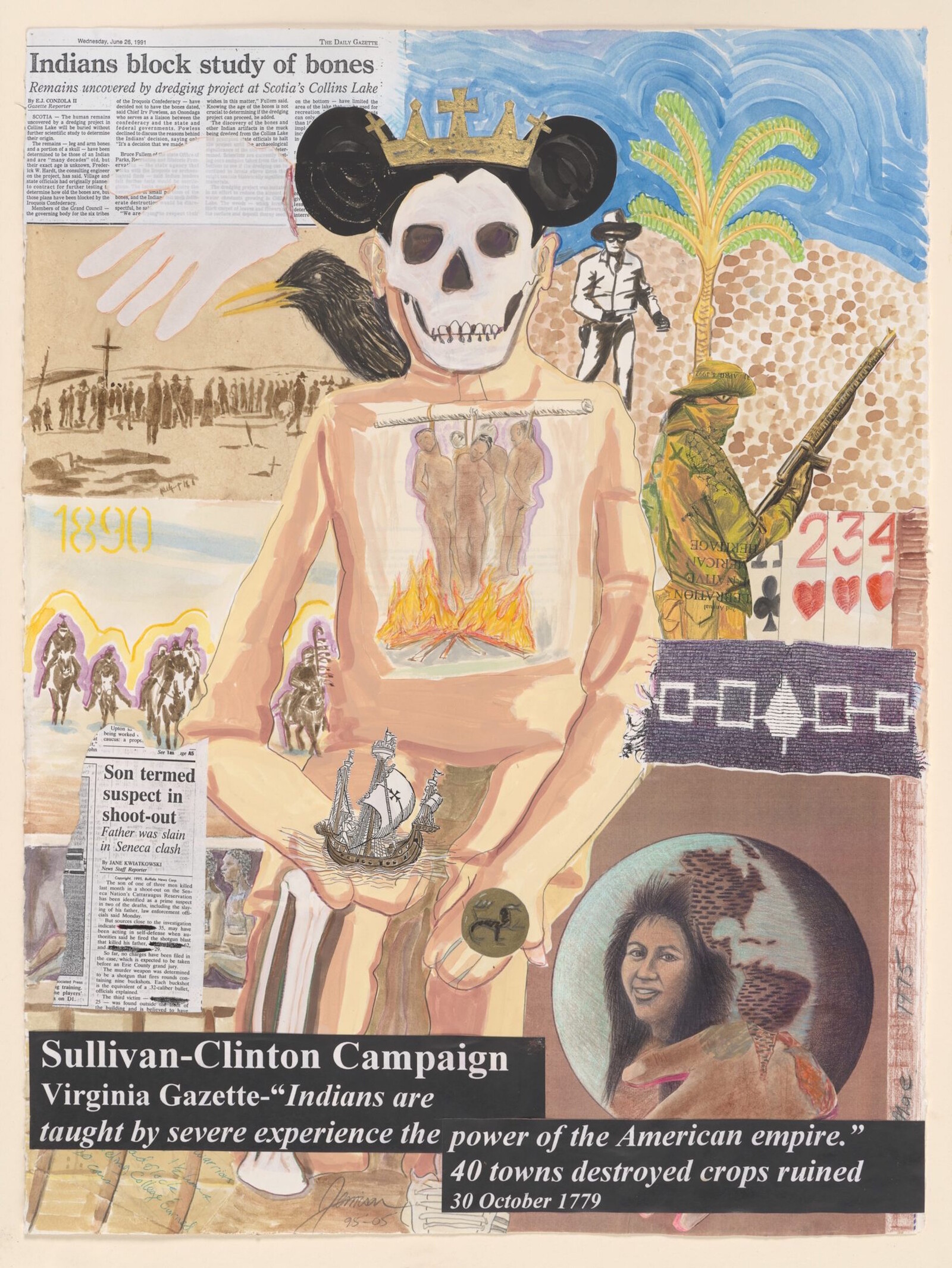

G. Peter Jemison’s colored pencil and crayon drawings on brown paper bags and multimedia collages are some of the best arguments for extra-institutional artmaking I have ever seen. Jemison is an enrolled member of the Seneca Nation, and “Greater New York” has made a point to include a number of artists who are also tribal members. The curators should get credit for putting together a show that feels like it legitimately reflects the demographic composition of New York City rather than the self-perpetuating racial homogeny of artistic canons. BlackMass Publishing, an independent publisher founded by Yusuf Hassan and devoted to books and zines by black authors, turned a small gallery into a reading room. Photos by Hiram Maristany of the Young Lords were a surprising but important addition, and artists from Brazil, Iran, Lebanon, Tunisia, India, and Egypt are represented. The list goes on.

I know that the list goes on, because everyone’s nationality or tribal affiliation is posted by their art. This, rather than strengthening the curators’ statement against racially exclusionary art practices, or challenging the viewer, transforms an actual and largely successful effort into a self-congratulatory and problematic gesture. I cannot stress enough how important it is to actively diversify the artistic production on view in major institutions. Hiding behind “death of the author”-style arguments is no longer acceptable. But there is something disturbingly close to Enlightenment taxonomies of race here. The implication is that knowing the race or nationality of an artist conveys some particular information about the person or what they are doing or intend to do. This is the logic of racism. Biography can, of course, convey meaningful knowledge. When Burns recites “I hate Doris Day/I hate Chevrolet/I hate Norman Bates/I hate the United States” and asks questions about sublets and gentrification, the fact that she is a Native American from Kansas living in Manhattan’s Lower East Side matters. But more often than not, this census-style foregrounding of official identities reinscribes hierarchies by directing viewers to consider race or nationality as a significant, if not primary factor, in the production and display of the work.

The wall texts reflect a haziness of intention that was apparent throughout the show in obscure gallery arrangements and series of work by single artists that were split between floors for no apparent reason. The labels exhibit the sloppy political thinking that often accompanies jargon-laden curator speak—language that allows you to feel like you’ve said something profound or politically radical without thinking your way from one end of a sentence to another. The press release sets out a series of oppositions, like the stated formal principle of “bridging” surrealism and documentary, that aren’t necessarily opposite in any meaningful way. Narratives are “specific and expanded” while “social and personal” experiences are about “belonging and estrangement.” Sure, this sounds good, but you can’t just make a list of contradictory couplets, punctuate it with the full-stop of land acknowledgements, and expect it to operate as an effective critical drag-net. Nor should you want it to. Saying everything is tantamount to saying nothing.