The two acts for which VALIE EXPORT is most famous are naming herself off a pack of cigarettes and a performance that involved wearing a pair of trousers with the crotch cut out, exposing her vulva. The Austrian artist, so associated with this bold punk aesthetic, represented her nation at the Venice Biennale in 1980, a rare occasion of recognition for a woman artist at the height of her career rather than its tail end, coming at the peak of her most prolific decade. Collecting these pieces together again, almost 40 years after they were shown at the Austrian Pavilion, makes clear how over time, the shock element of EXPORT’s art has faded, yet what remains is an always-pertinent critique.

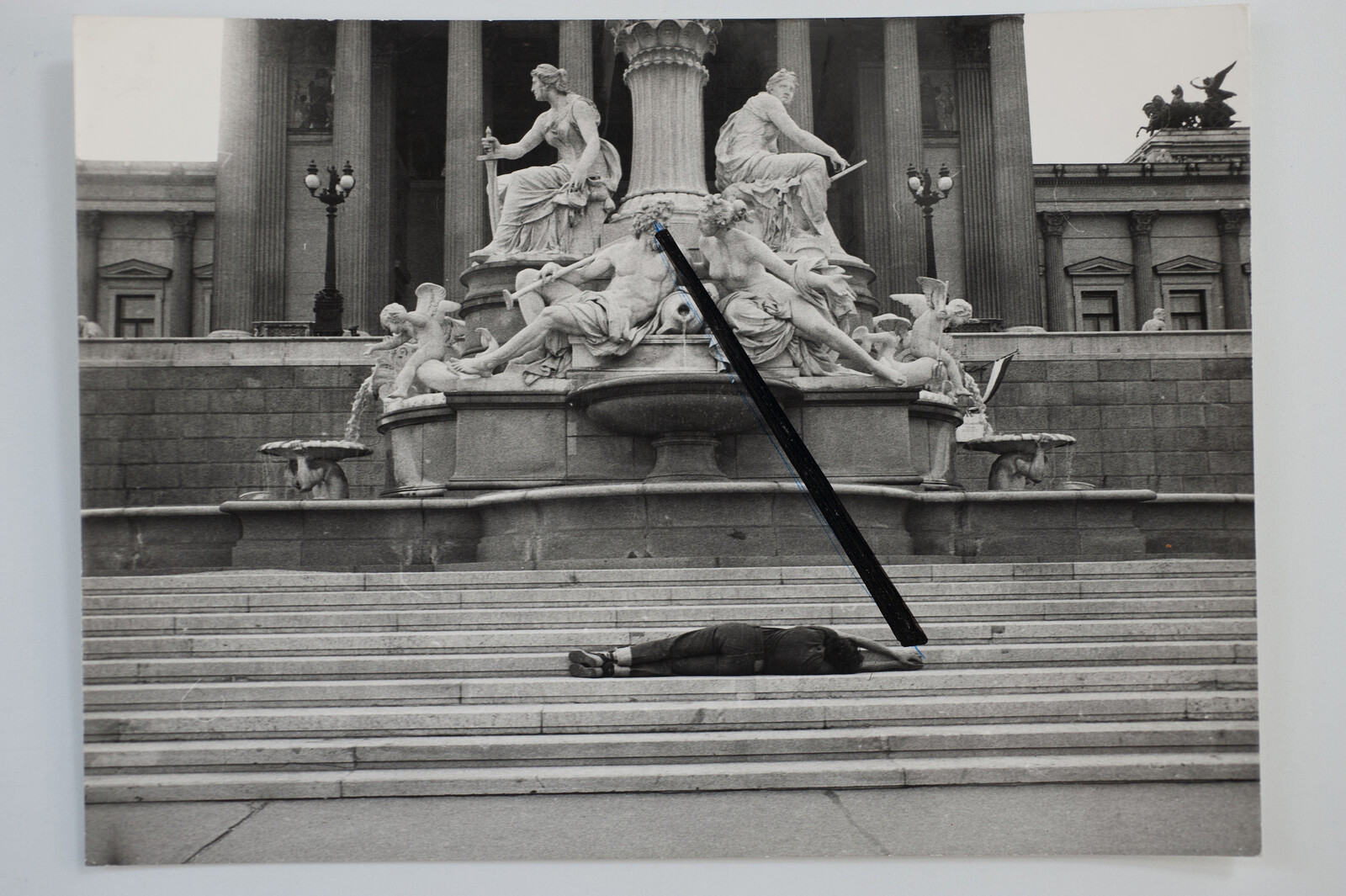

EXPORT’s work is a reflection on the place women are afforded—that is, must fight for—in the communities in which they live. On view is “Body Configurations” (1972–76), a series of black-and-white photographs that show EXPORT adjusting her body to the city—lying with her back arched to match a curve in the pavement in ABRUNDUNG I [Rounding I] or sitting against the corner of a building, her hands stretched to touch its two sides in VERFÜGUNG I [Available I] (both works 1976). This series, which at times includes colors (there’s a version of ABRUNDUNG, also from 1976, called Einkreisung [Isolation] in which the pavement’s edge is dyed red) and black lines drawn between EXPORT’s gesture and the cityscape into which she inserts herself, hones in on the female body and the way it is experienced in public space—always in question, never fully fitting in.

There’s an ominous undertone to the work. The self-harm in the film Remote…Remote… (1973), takes a while to appear: EXPORT is sitting, a nail clipper in hand and a bowl of milk between her legs. The white, pure milk, the fragile skin being cut—what’s coming is so clear that when the first drop of blood sullies the white liquid it’s almost a relief. Similarly the documentation of HOMO METER II (1976), a performance where EXPORT walked down the street with a large round loaf of bread tied in a string to her neck resting against her stomach, and invited passersby to carve themselves a slice. Then, look again at the photographs of EXPORT in the streets of Vienna, contorting her body to fit street furniture and curves in the road. The underlying violence is a reflection of how women experience the world.

Then, in the center of the gallery, is Geburtenbett (1980). The title, which loosely translates to “birthbed,” hints at the work’s subject but not its foreboding nature. A large rusty installation comprised of a steel frame with bedsprings in the back, a pair of white fiberglass women’s legs, and a small monitor taking up the space that would be this figure’s chest and head, showing a priest conducting mass. From the legs emerge red fluorescent tubes, reminiscent again of blood. Across the show are spread religious symbols, like bread and blood: these coalesce here in this half-woman’s body, a place of no redemption.

EXPORT shared the Austrian Pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale with Maria Lassnig, a painter 20 years her senior. The pairing of Lassnig’s angst-ridden figurative paintings, especially full-length, non-idealistic portraits of women, often in the nude, and EXPORT’s work is astute. But while the Ropac exhibition includes a couple of vitrines showing archival material from the Venice presentation, with photographs from the opening, sketches for Geburtenbett, and notes, nowhere does it communicate to a contemporary viewer in London what the original exhibition really looked like: there’s no sense of how it was installed or how the relationship between Lassnig and EXPORT’s work manifested.

Restaging a historical exhibition without this kind of information mainly serves to consolidate the image of the artist-hero, but it isolates EXPORT from other feminist artists. The thought of her body-oriented works next to Lassnig’s supports other connections, first and foremost between “Body Configurations” and its exact contemporary, Ana Mendieta’s “Silueta” series (1973–77), in which Mendieta documented herself performing nude in the landscape, fusing land art and performance in works that explored gender and place, especially in relation to her experience as an immigrant. To see EXPORT trying to fit her body to the urban environment she inhabited, and think of Mendieta attempting to trace her body’s contours through nature, is to realize just how much their thinking aligned at the same time. William Gibson, in a 2011 interview with the Paris Review, talks about an idea science-fiction writers called “steam-engine time”: “when suddenly twenty or thirty different writers produce stories about the same idea. It’s called steam-engine time because nobody knows why the steam engine happened when it did. Ptolemy demonstrated the mechanics of the steam engine, and there was nothing technically stopping the Romans from building big steam engines.”1 If the early 1970s were steam-engine time for exploring the struggle of women for recognition—in public space and in their own fields—through this body-oriented performance, then it’s no wonder both EXPORT and Mendieta’s work feel so current in the contemporary, adversarial moment. All work to undo the erasure of female artists from history is crucial; it is also time to highlight their alliances.

David Wallace-Wells, “William Gibson, The Art of Fiction No. 211,” the Paris Review vol. 197 (Summer 2011), https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/6089/william-gibson-the-art-of-fiction-no-211-william-gibson.