There are many ways to move through and think alongside Ethan Philbrick’s Group Works. At first glance, it’s a book of academic theory coming out of performance studies. Following a “desire for collectivity,” Philbrick takes the small-scale formation of “the group” as the locus of inquiry. He enters the text with a tentativeness toward groups, recognizing the ways that they are frequently viewed with healthy suspicion or uncritical celebration. He asks:

What kind of good-bad thing is a group to do?

When do we do things in groups, and why?

How do we group, and how does that matter?

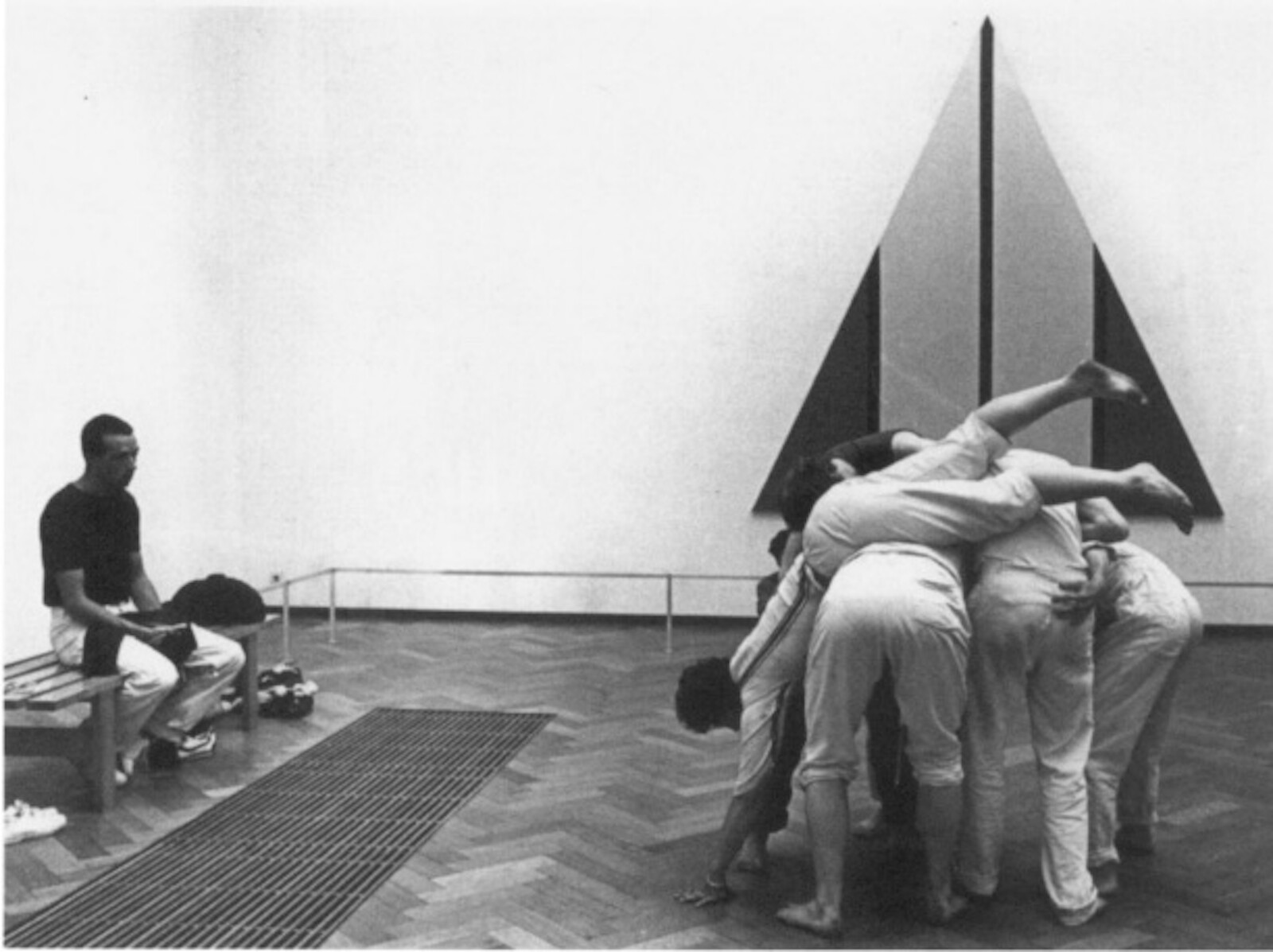

Moving with these questions, the book turns to artists experimenting with novel group formations in dance, literature, film, and music in the 1960s and ’70s. Each chapter pairs a “group work”—Simone Forti’s 1961 performance Huddle, Samuel Delany’s 1979 memoir Heavenly Breakfast: An Essay on the Winter of Love, Lizzie Borden’s 1976 film Regrouping, and Julius Eastman’s 1979 musical piece Gay Guerrilla—with contemporary works that re-imagine, re-perform, or dialogue with these experiments. Taken together, each pairing amplifies and extends the book’s central impulses to consider how groups assemble and disassemble. Along the way, Philbrick introduces a chorus of thinkers—theorists of community, theorists of in-operative community, theorists of the provisional, the ongoing, and the convivial: José Esteban Muñoz, Cauleen Smith, Fred Moten, Joshua Chambers-Letson, Tavia Nyong’o, and many others. He calls the book itself “a group work masquerading as a solitary project.”

What emerges in refrains of the book’s intergenerational ensemble is both an ambivalence and a cautious hopefulness about the possibilities of small-scale collectivity. For Philbrick, the group is not a “stable, idealizable entity” but a rehearsal for assemblies yet to come. The experiments of the past are not romanticized as “utopian blueprints” to be replicated in the present. The artists making work in the 1960s and ’70s engaged the group as a complex aesthetic form in which to grapple with larger socioeconomic shifts taking place in the world; their small-scale formations offered a continuous space to disentangle—structure, language, ways of relating—and to reassemble questions and modes of living in common. Philbrick surfaces their flawed and ephemeral formations as a resource for those of us drawn—politically, artistically, and pedagogically—to the small group as a site of political and artistic life today. Instead of being interested in whether a group is a “good” or “bad” thing, the book attends to the messy ways that groups form, occasionally fall apart, and continuously remake themselves. Or in other words, it considers how we might gather in and with collective ambivalence.

The book ends with a return to its initial questions. It also extends an invitation to “collectivize” the very act of reading, closing with a series of scores meant to be enacted and practiced. These include:

Get a group of people together for a meeting but never call it to order.

Create a structureless structure.

Write after the end of something.

Philbrick’s scores invite readers to convene on the periphery of the book’s questions—to hover in their impasses, to tend to their generative crises, to literally get together with others. Following a diverse tradition of musicians, dancers, and visual artists—Pauline Oliveros, La Monte Young, Allan Kaprow, Yoko Ono, Cornelius Cardew, Anna Halprin, and many more—who have created scores as collective prompts for artmaking, the scores in Group Works “blur the relationship between a book and a practice, between reading and doing.” They provide practical tools for small-scale assembly. They call for the formation of a group. Here, composer Annea Lockwood’s reflections on the 1970s magazine Women’s Work feel apt: “We wanted to publish work which other people could pick up and do […] this was not anecdotal, this was not archival material, it was live material. You look at a score, you do it.”

After finishing Group Works, I wondered what it would mean to take the book seriously as a score, a prompt, or a site of convening. To read it non-linearly or incorrectly. To rehearse it.

I decided to convene a gathering, sending a somewhat vague invitation to a group of friends in Los Angeles and asking if they wanted to share a meal and talk about the book (which none of them had read). A few days later, ten of us huddled in my living room. After a wide-ranging conversation about what made a “group” and groups we were or had been a part of, we read aloud passages from Group Works, tried out the closing scores, and decided to write our own:

Invite people to a dinner party and never serve a meal.

Imagine a ritual to prevent a group from forming.

Name all groups that you cannot ungroup yourself from.1

Given that no one except me had read Group Works ahead of time, it felt exciting that in just a few hours, we had inhabited its provocations, traversed its affects, and found our own way to activate its animating questions.

In turn, taking the book seriously as an invitation to read collectively, to even misread, became an occasion to think about both the purpose and possibilities of critical reading. The book fundamentally asks: What can a book do? How might a book become a practice? As someone who also shares a “desire for collectivity,” I found a new set of questions emerging: How can we enact a book in a way that is generative, generous, and social? Can criticism be a practice of hosting? Can the book be a party, and if so, how might we both host and join that party?

If we take these questions seriously, Group Works offers not only a rich and fascinating academic exploration of artistic small-group formations past and present but also a tentative scaffolding to experiment with our forms of reading and study. By asking how we come into and out of groups, how they coalesce and disassemble, the book invites readers to join in and elaborate its collective impulse.

These scores were generated during an informal Group Works gathering on 23 July 2023 in Mt. Washington, Los Angeles with Chika Okoye, Lois Beckett, Ashley McNelis, Corina Copp, Patricia Ciccone, Kameron McDowell, Emma Baretto, Sam Swift, A.J. Nielsen, and Laura Nelson.