Every time I approach White Cube’s gleaming south London base, I am reminded of a trope in science-fiction films: a professor of linguistics is whisked to a top-secret government facility, decontaminated, and introduced to an alien intelligence whose ominous burps she is tasked with translating. These daydreams are no doubt prompted in part by mental association with Brian O’Doherty’s Inside the White Cube (1976), which drily observes that the “ideal” contemporary art space “must be sealed off from the outside world” in order to preserve the closed system of values that operates within it.1 But pulling on a mask, sterilizing one’s hands, and confirming one’s identity with a security guard lends these visions a new lucidity.

Beyond the hermetic seal, Cerith Wyn Evans’s experiments in sculpture and installation are right at home within the self-contained network of relations that O’Doherty describes, with a roomful of smashed glass screens referencing the high-modernist touchstones of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23) and its documentation by Man Ray. Two potted trees rotating slowly on turntables, their branches splayed over a cruciform bamboo trellis and illuminated by a spotlight that casts their silhouettes over the far wall, suggest an artist stepping tentatively (and not entirely convincingly) beyond the field of signifiers to comment on one aspect of the world’s multifaceted collapse.

For all their allusions to a century-old avant-garde, the spectacular technical accomplishment of works like 9 x 9 x 9, fig. (0) (2020), in which an exploded helicopter is line-drawn in space by a snarl of neon splinters suspended from the ceiling, would reward an audience untrained or uninterested in identifying them. Yet the feeling lingers that the necessity of limiting visitors to appointments protects not only people—I have an hour to myself in this vast space—but also the fragile ideological infrastructures maintaining the economic and cultural value of contemporary art.2 This exhibition was, like almost all of those now open in London, installed before the city shut down. Its best work, excepting some dud paintings, would benefit from encounter with a wider public and the ideas they carry in with them.

That the meaning of a work of art is in part determined by the experience of its interpreter is reinforced, at Marian Goodman, by Rineke Dijkstra’s Night Watching (2019). Displayed on a triptych of screens, the video shows groups of people looking at, and talking about, Rembrandt’s The Night Watch (1642). They are depicted face-on against a white background, suggesting that the artist erected a screen in the Rijksmuseum against which to shoot them. The edited discussions play to type: a phalanx of Japanese businessmen speculate on the economic model underpinning an ensemble painting commissioned by its subjects; a gaggle of art students muse on iconography and commodification. The work suffers by comparison to its more affecting predecessor The Weeping Woman, Tate Liverpool (2009), for which the artist recorded the reactions of school groups to the eponymous Picasso. The lesson might be that children, because they haven’t yet internalized the ways of thinking that outfit them for life in a society hostile to creativity, respond more imaginatively to art than their intellectually hidebound elders.

Either way, the reminder that art can reward readings as diverse as its audience only highlights that the rest of this show—photographic portraits of mostly adolescent siblings—does not. On the ground floor, unnervingly self-possessed sisters and brothers are pictured in domestic interiors ranging from elegant (Arden and Miran, London, February 16, 2020) to opulent (Marianna and Sasha, Kingisepp, Russia, November 2, 2014). On the first floor, a classically beautiful space washed with sunlight from the atypically bright London sky, a suite of twenty-one photographs of three sisters—the artist encountered them in an Amsterdam park—taken at seven annual intervals runs in repeated triptychs around the walls.

Emma, Lucy, Cecile (Three Sisters) (2008–2014) (2016) aspires, like the celebrated British television series Seven Up (1964–present), to describe the passage of time through the changing features of its subjects. But it is jarring, having stepped off the streets of London, to be surrounded by white faces, and the abstraction of these sisters from any context (they are also shot against blank backgrounds) seems to downplay the influence of external factors on the people they are in the process of becoming. It may be that this quasi-neutrality was thrown into sharper relief by the contrast with my previous visit to the gallery in January, when Nan Goldin’s wildly popular “Sirens” presented a markedly different society—racially diverse, genderfluid, economically precarious, communitarian, marked by and active in a sullied world—to an audience resembling its subjects.

Where Night Watching absents the work of art in order to focus on the emotions it provokes, the sculptures of Alina Szapocznikow work in the opposite direction, packing every conceivable extreme of human feeling into forms contorted by suffering or desire. Take Sculpture-Lamp (1970), included in a narrow but impactful survey of her late work at Hauser & Wirth: a lightbulb atop a phallic stem shines through a pair of pursed and painted woman’s lips, the only intact part of a skull that crests into a breaking wave of yellow and pink polyester resin. In its use of colloquial forms to express intense psychological experiences, its series and sequences, and its rejection of metaphor in favor of direct expression, Szapocznikow’s late work resembles confessional poetry, in which life is not a technical problem to be solved but an arena of feelings to be explored. The show is complemented by the installation, in the gallery’s neighboring space, of Isa Genzken’s more austere but no less unsettling “Window.” The deconstructed passenger jet at its center reads like the set design for a play staged in the wake of a plane crash, and prior to the lockdown I envisaged its characters squabbling over resources on their desert island. After months of quarantine, it has been recast in my mind as an absurdist monologue in which the sole survivor waits vainly for salvation.

Which is to say that works of art, no less than bodies, are vulnerable to the contexts in which they are placed. So it was disconcerting, even before the lockdown and protests, to watch Hito Steyerl’s November (2004) and Lovely Andrea (2007)—paeans to her murdered activist friend Andrea Wolf that double as exhortations to revolutionary action—from the bottom step of a bifurcated marble staircase in Thaddaeus Ropac’s Mayfair townhouse. The curators of this joint exhibition with the late Harun Farocki protest that siting critiques of capitalist labor forms in these environs “open[s] up a crack in the system of art,” which sounds a little like having one’s cake and eating it, but does at least productively foreground the dissonance. Only Steyerl’s The Tower (2015/2016) now remains open to the public, though works including Farocki’s Comparison via a Third (2007) can be viewed via the gallery’s website. The work to lose most from the migration online is Farocki and co-curator Antje Ehmann’s Labour in a Single Shot (2011), whose short films documenting workers from Bangalore to Buenos Aires were originally projected onto a zigzag of hanging screens.

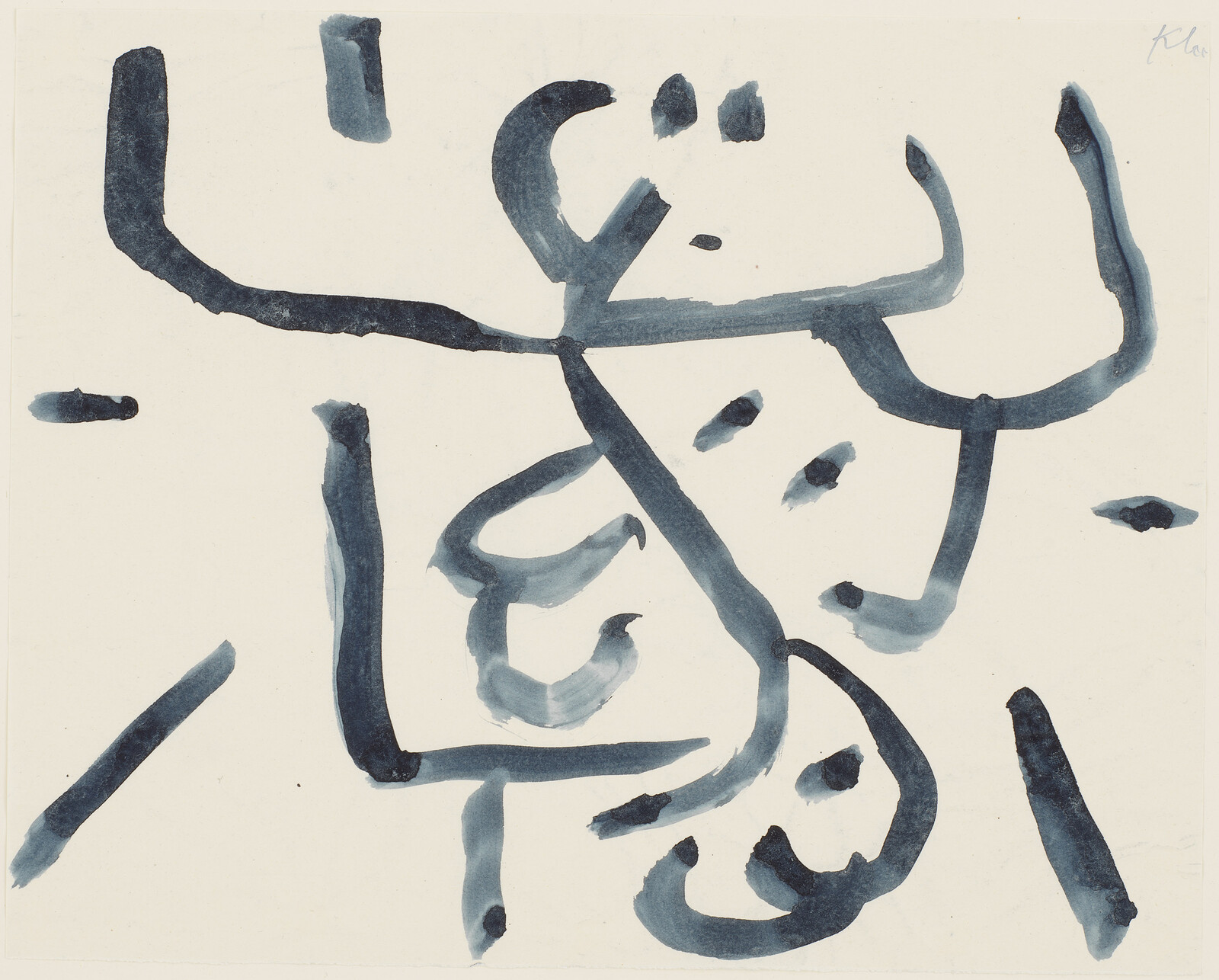

It’s unlikely that a few pithy sentences about the late drawings and paintings hanging at David Zwirner will contribute significantly to the critical understanding of Paul Klee’s career, but their energy and invention survive even the aseptic conditions in which they are encountered. A mischievous Clown als Knabe [Clown as Boy] (1940), to take my favorite example, seems determined to break out of the exquisitely tasteful frame in which he is imprisoned. I don’t expect the gallery to pin Klees to the wall, but the imaginative effort required of the viewer is to free these witty and wry works from the air of high seriousness that suffocates them. You have to keep in mind both that the chalk and pencil sketches are trivial, and that this triviality is evidence of the type of unfettered imagination required to think transformationally. Suffice to say that the show is worth seeing.

Similarly, the historically “minor” styles and subject matters of Ella Kruglyanskaya’s paintings—group portraits of stylish women executed with the energetic line of a mid-century fashion sketch—convey more about the present than any number of history paintings, and succeed in making work that strains for high seriousness look self-conscious or conceited.3 New works including Lemon, Peel, Milk (2020) and The Arrangement (2019) are arranged amidst a crowd of drawings and paintings at Thomas Dane Gallery that now feels disconcertingly busy; combining still life, trompe l’oeil, and portraiture, they reconcile intellectual playfulness with technical ambition. The artist does not so much fulfil her early promise as extend its limits, clearing more space in which to work.

O’Doherty wrote of the white cube that it expresses “lots of period (late modern)” but “no time.” He means that the architecture—physical and ideological—of the contemporary art gallery is designed to insulate its contents from the world outside. I am wary of reading art only through the lens of a media cycle that returns too intermittently to certain issues before moving too quickly away from them, and it should be reiterated that all of the above exhibitions were installed prior to the lockdown and the protests that effectively marked its end. London’s smaller and mid-sized galleries—closer to the ground and quicker to act—reopen later this week,4 and so it remains to be seen whether and how the turbulence of this time will penetrate into the spaces reserved for art in the capital of a rapidly changing society. The only certainty is that there can be no return to what once passed for normality; whatever comes next must be new.

O’Doherty means “ideal” in the Platonic sense, rather than “most desirable,” though he is also playing on the conflation of the two meanings.

To be clear: this isn’t to lay blame at the doors of galleries, which deserve credit for having opened their doors, but to state that art is strengthened by exposure to an audience and weakened by existence in a vacuum.

For more on the Kruglyanskaya’s show, read her interview with Rachael Allen: https://www.art-agenda.com/features/335508/a-boundary-to-throw-one-s-body-against.

I look forward to seeing Hannah Black at Arcadia Missa, Marie Jacotey at Hannah Barry Gallery, and a group show at Hollybush Gardens, among others.