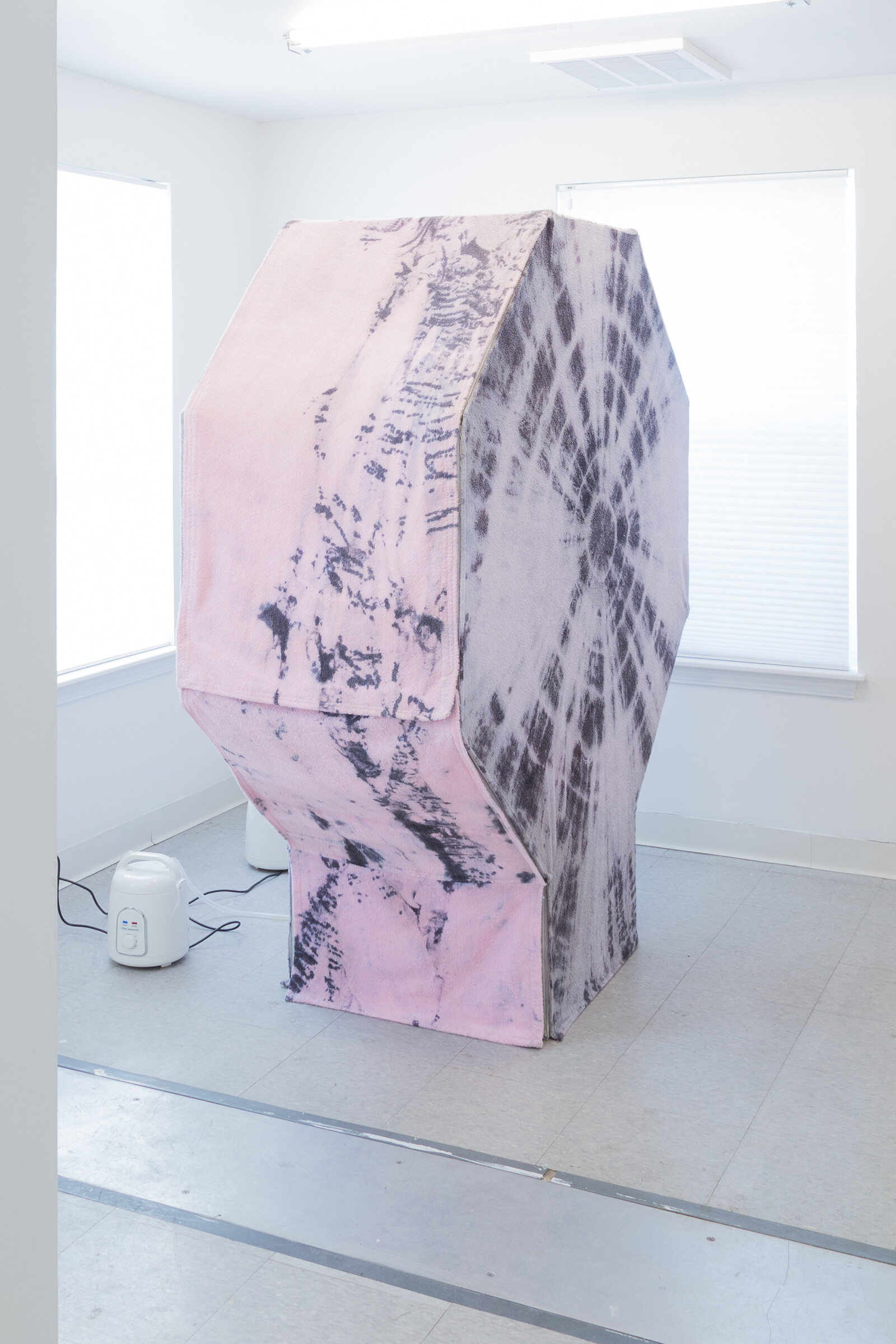

Rather than the Belgian town of Spa, where, starting in the sixteenth century, the diseased and melancholic would drink chalybeate and engage in other watery therapies, I was in Detroit, sitting in SAUNA SHELF by Nicolas Lobo (all works 2019). The one-person octagonal sauna was encased in pink waterproof fabric, pulled taut and tie-dyed with black, marbled patterns. With deep breaths of the mist pumping in, my lungs and dermis chemically merged with the Vicks VapoRub and cuttings from the red cedar tree in the yard out front. This was the first recommended step in Lobo’s exhibition “Wellness Center,” located in the final project completed by artist Mike Kelley before his apparent suicide. Mobile Homestead (2006–13) is a replica of Kelley’s childhood home, a ranch-style house in the Detroit suburb of Westland. The full-size replica, which stands next to the parking lot of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, is used for community gatherings, AA meetings, and exhibitions unrelated to Kelley and his work. As I sat in Lobo’s sauna, an artwork within a larger artwork, listening to the hum of a nearby fridge, my senses of public and private, wellness and not-so-wellness, started webbing together.

Half an hour later, I emerged moist and pliable. I rejoined Michael Goe, the education assistant who was ushering my visit, and Amy Corle, curator of education and programing for Mobile Homestead. Corle’s office is located where Kelley’s childhood bedroom would have been. I peered into the closet. A hatch with a ladder leads down to the basement and the “sub-basement.” Contrary to the top floor, which is very open to the public, this area is a warren of tunnels and claustrophobic spaces reserved for those approved by the Mike Kelley Foundation. I can’t comment on the things rumored to occupy those depths, but artists and others have placed artworks there, held performances, and executed, shall we say, ritualistic gestures. Mobile Homestead grew out of Kelley’s attempts to buy his actual childhood home—he’d show up checkbook in hand—and turn it into a community space. He’d also fantasized about tunneling under neighbors’ properties, testing the subterranean boundary of trespass. Standing in the doppelganger space of Kelley’s boyhood bedroom, I felt awash in the uncanny: Why did Kelley place the underground hatch in the closet? Why was he obsessed with the home he grew up in? And, maybe most importantly, why was I trying to read his childhood for an explanation of his later life? My curiosity turned to sheepishness, realizing I was in fact standing in a curator’s office with a towel around my waist, no shoes or shirt on, dripping water on the floor.

The next step in Lobo’s exhibition was to drink some orange juice. The installation Juice Trader included a bodega-style fridge containing cartons of Tropicana, SunnyD, Welch’s, Mountain Dew Kickstart, and other vaguely orange beverages. The two-channel video on the wall shows two glasses being filled with what becomes, over repeated viewings, a foreboding orange fluid. The wall text reminds viewers that Tropicana is a vile facsimile, “juice” that is deoxygenated, stripped of flavor as it’s heated and stored in million-gallon vats, then re-flavored with orange oils and essences—perfumed, essentially. I picked up a bottle of California Garden. It came with “Real Fruit Pieces” that had a plasticky bite to them.

In past works, Lobo has examined cough syrup, pirate radio, napalm, swimming pools, Kevlar, and lipstick. From the military R&D that so often begets consumer products and services to the systems that produce and circulate them, his research in the last few years has focused on luxury, and now wellness. In the room after Juice Trader was the “Hydrogel Paintings” series, made during therapeutic sessions with people in Lobo’s studio. Used hydrogel face masks, medical-grade honey, cannabis pain creams, activated charcoal, rose kaolin, and other substances were applied to glass and photographed at different points in the day, the photos then transferred to aluminum with UV ink. The sublime paintings, with their varying transparencies and floating, ghostly masks, have the qualities of petri dishes and art nouveau panels, with titles that are as poetic as any luxury spa menu: NEPHTHYTIS, TURMERIC, STEM CELL GOLD PARTICLE.

I then went outside to the backyard and took a shower with Lobo’s 1979 ASMR MASSAGE SHOWER SHELF. Modeled on an étagère by mid-century modernist designer Milo Baughman, the shower’s aluminum diamond grid holds ceramic tablets with indentations created by following a tutorial for ASMR massage. It was impossible not to think of the connections between the Fordist, nuclear-family pragmatism of the Kelley home and the globalized, modular flows that Lobo is examining. The highly individualized, highly curated self-care products of the twenty-first-century home rely on the aesthetics of responsibility and sustainability. But undergirding this, as with the postwar American suburb, is pollution, exploitation, and misery.

With the fake orange taste in my mouth, the shower pumping cold water under a dazzling sun, I wondered if Lobo’s works had maybe integrated a little too seamlessly with their subjects and critiques. Yes, he celebrates (and laments) the unrealized potential of self-care regimes as systems for collective care. But the mask of contemporary art and design felt too heavily applied—the works too slick, too ready-made for an economy just as foul as wellness’s. These thoughts aside, I did, however, feel very relaxed.