“Can’t I accept the reality,” photographer Claudia Andujar wrote in her notebook during a 1976 trip to the Yanomami territories of the Brazilian Amazon, “of the poorly resolved contact of the Indians with the ‘Whites’…? Do I want to delude myself? Do I now want to prove that here I found simplicity of living?”1 By this point Andujar, who has been depicting and advocating for the Yanomami for the past 50 years, had already begun to witness significant changes overtaking these communities, due in large part to the influx of state infrastructure, agricultural projects, and missionaries. Her body of work over these decades is imbued with a belief that an empathic and creative depiction of the indigenous group could help protect them from the same societies that consume these images. Her recurring approach is “salvage,” in the anthropological preservationist sense, and has moved towards that goal through artistic representation, ethnography, and direct activism.

Fondation Cartier’s retrospective “The Yanomami Struggle,” which was first initiated by Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, traces Andujar’s relationship to the Yanomami, and presents a biographical, anthropological, and psychological portrait of Andujar herself. Born in 1931 in Switzerland to a Swiss mother and Hungarian Jewish father, and raised in Transylvania, Andujar fled Europe in 1946, after having lost her father and many members of her extended family to concentration camps. She travelled first to the United States, where she began developing her artistic practice, and in 1955 relocated to Brazil. There, she became a photojournalist, focusing on marginalized communities, including small towns and indigenous territories: she first visited the Yanomami on assignment in 1971. From that point on, documenting, understanding, representing, and defending these people became a major project that continues to the present day. Andujar’s mediating identity, as a European outsider negotiating between a development-obsessed modern Brazil and the indigenous communities, is a theme that subtly weaves through the show alongside personal details, which suggest a traumatic link between Andujar’s early history and the threatened existence of the Yanomami.

The exhibition frequently narrates Andujar’s work through her own voice, alongside those of two long-time collaborators: anthropologist Bruce Andrews, and Yanomami shaman and activist Davi Kopenawa, whose testimony provides the introductory wall text. Andujar, he explains, “is not Yanomami, but she is a true friend […] she taught me to fight […] she gave me the bow and arrow as a weapon, not for killing whites but for speaking in defense of the Yanomami people.”2 That the exhibition should need to start by asserting legitimacy from the subject is awkward but understandable, given the fraught ethnographic and social documentary artistic constructs—attempts to capture acts of natural daily life among the “other”—that much of the work resembles. However, what would be really something is if the exhibition had also outlined why it needs to assert that particular kind of legitimacy. To do so would acknowledge that the discourses surrounding indigenous agency, culture, and ontology in anthropology and art have, in recent years, begun to comprehend that the language, actors, tools, narrative styles, and aesthetic priorities of visual encounters must be led by the subjects themselves. This shift is due in large part to the art and advocacy of native and indigenous artists.

From this opening, the exhibition is plotted by descriptive chronologies, as time periods match up with themes: “Rite and Invention,” “In Search of an Identity,” “From Art to Activism.” It opens with a selection of Andujar’s most emblematic and eye-catching photographs: documentary mixed with sensory interpretation of elements of Yanomami cosmology, including their origin story, which involves the procreation of a demiurge and an aquatic monster, and the existence of the xapiripë, or spirit guide of the forest, which can be accessed through shamanic rituals and the ingesting of yakona, a hallucinogenic powder. The images employ a variety of techniques: wide-angle lenses; infrared film (the documentary use of which was recently repopularized by Richard Mosse’s portraits of the Eastern Congo), which show the forest in bright pink saturated hues; and color filters, which bathe images in yellows, ambers, and rich blues. Andujar’s experiments with exposures and manipulation on the lens, meanwhile, can distort or soften the image. In some examples, she adds a halo around a subject to augment the shamanic trances present in the rituals she records.

This sensory approach recalls the late American ethnographic filmmaker Robert Gardner’s 1986 work Forest of Bliss, which—at the time controversially—presented burial rites on the Ganges as an immersive, disorienting, meditative experience, without common documentary additions like voiceover explanation, subject interviews, or intertitles. Although Andujar’s work does not explicitly engage with ethnography as a discipline, it responds to some of the same ethnographic constructs that Gardner’s experimentation addresses—the problem of asserting reality when one group depicts another; the intrusion of the photographic device—and stands in contrast to the notable anthropological takes on the Yanomami, such as Napolean Chagnon’s Yanomamö: The Fierce People (1967), which depicted the group as paternalistic and perpetually warring. Like Gardner, Andujar’s early approach goes beyond attempting to transmit a photographic reality; this is an effort to offer a cohesive portrait of a world as she experienced it.

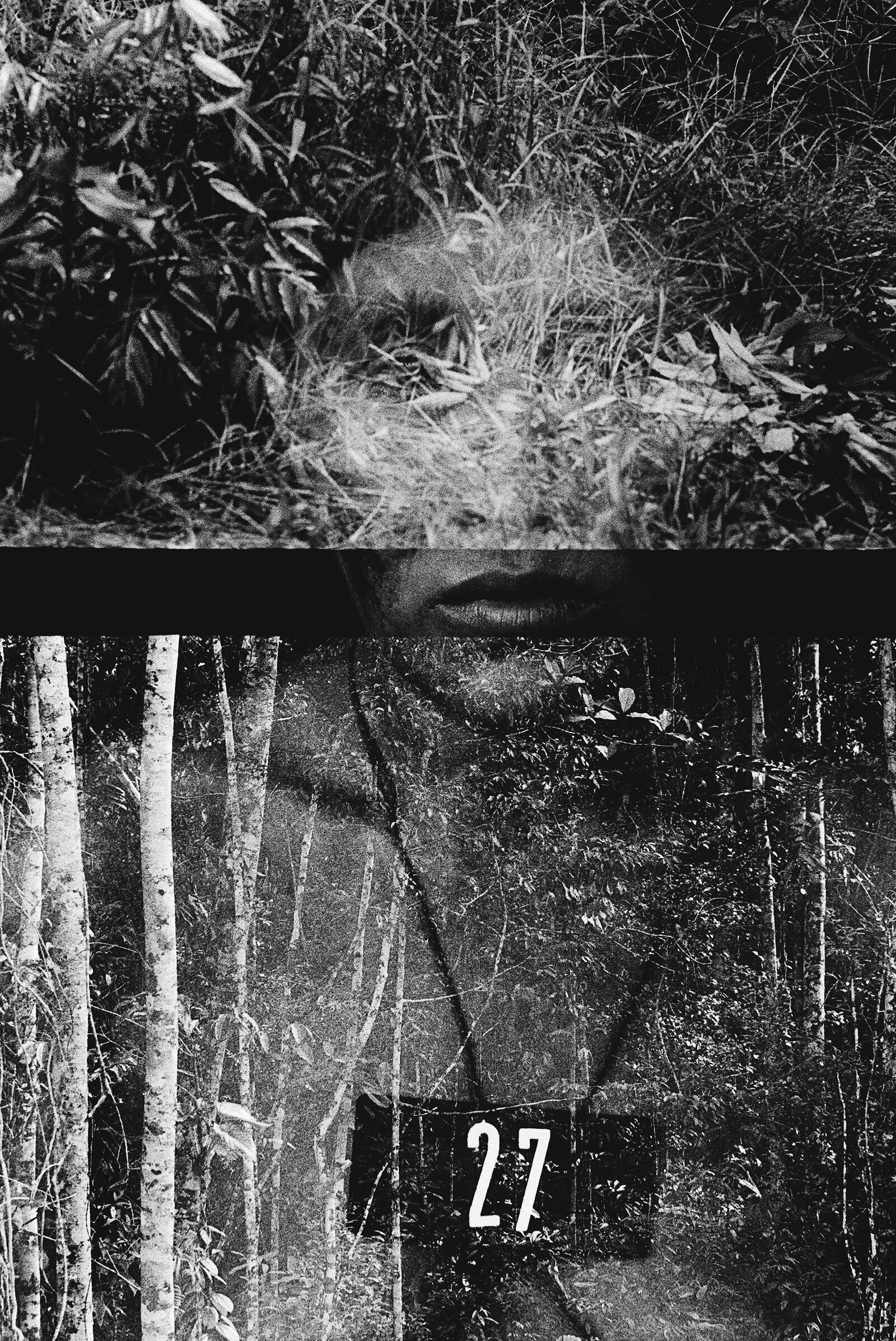

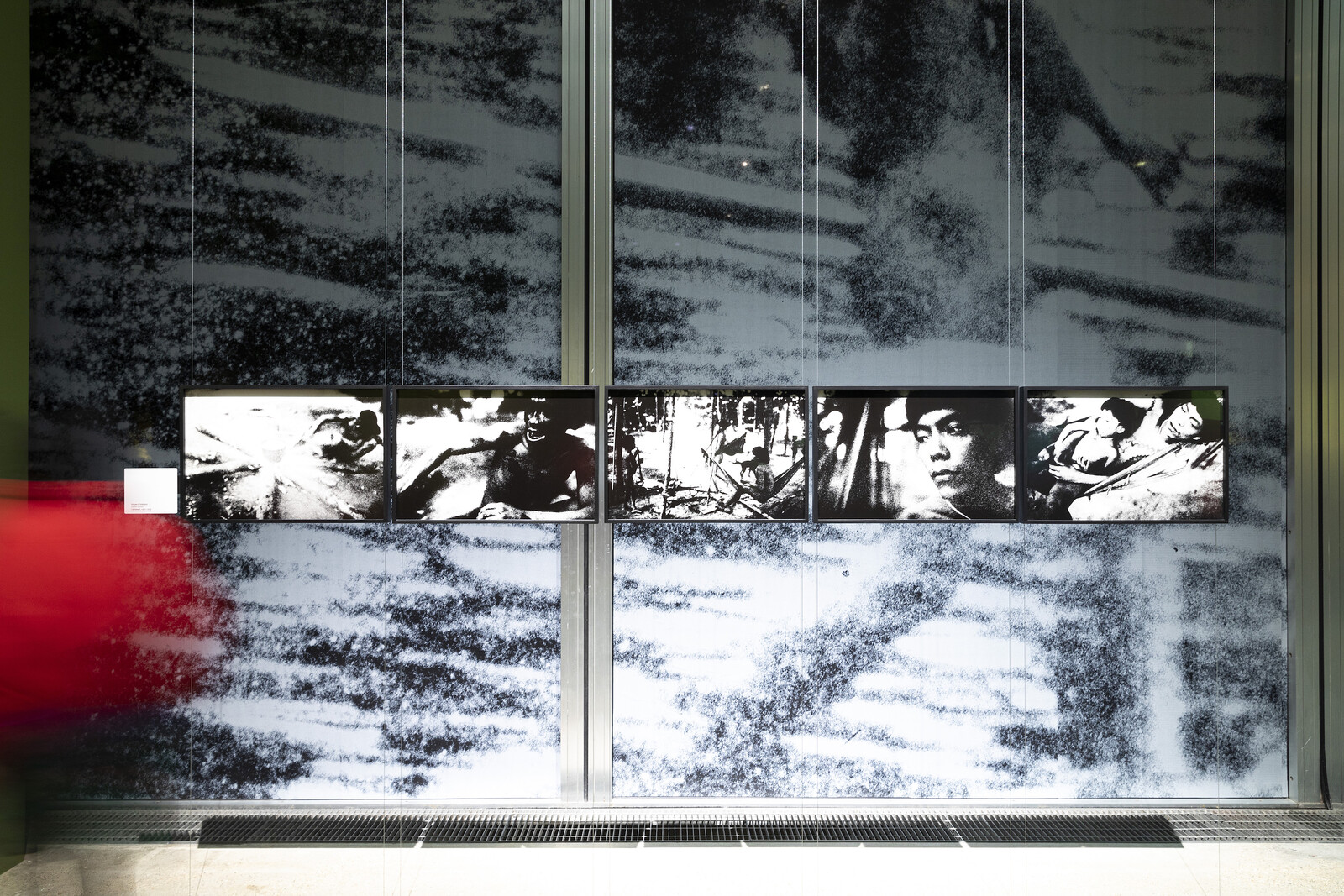

Much of her later work, shown in the exhibition’s second half, is less dreamy and vibrant, and more direct in its appeals. The worsening development situation, and ongoing disregard for indigenous lives, seems to have led to a move to realism over creative practice. At several points over this period, the Brazilian state banned Andujar from visiting the territories on account of her activism, but she repeatedly found her way back. One frustrated series, entitled “Marcados” [Marked], repurposes documentation photos from a 1980 vaccination campaign. The original images were made for the purpose of record, not art, and show Yanomami individuals donning numbered tags around their necks, having just received their shots. In 2009, Andujar returned to these images, noting their similarities to her memory of the tracking and identification of Jewish people in 1940s Europe. The new works—still centered on these mug shots but with overlaid, fragmented images of body parts, community members, and local landscapes—point to the fact that the ethnographic and photorealistic depiction by the West of others has happened in parallel with genocide.

Anthropologist Audra Simpson writes in her 2007 essay “On Ethnographic Refusal”: “To speak of indigeneity is to speak of colonialism and anthropology, as these are the means through which indigenous people have been known.”3 For all the work of white allies in visual and documentary disciplines, NGOs, and anthropological sciences, this fundamental, structural imbalance remains. In his 2013 book The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, a first-person account of Yanomami life and beliefs, Kopenawa relates a straightforward example that outlines the deep ontological insufficiencies of Western religion and culture for Yanomami people: “To us, all these white people’s words about Teosi (God) are in vain. If one of my children’s image is captured by a koimari bird-of-prey evil being, it will be useless for me to […] talk to Teosi instead of calling the xapiri (spirit)! If I merely close my eyelids as if I were asleep and say: ‘Father Teosi, protect him!’ no one will answer […] My child will die and I will be left with nothing but my sorrow.”4

I think about this quote in comparison to Kopenawa’s praise for Andujar as a rare ally when, for many in the West, the genocide of indigenous peoples has been no barrier to brazen development and accumulation. “The Yanomami Struggle” traces a specific history of contemporary contact and encounter, and gestures at a broader history: of ethnography and documentary photography beginning to catch up with its own shortcomings. Seeing this project unfold over decades brings to the surface numerous moments of humanity, but also devastating failures. In the lessons of those failures there is at least some potential to find new weapons in the struggle.

Thyago Nogueira, Claudia Andujar, The Yanomami Struggle (Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2020).

The term “white people,” frequently employed by Davi Kopenawa in his writings, appears to apply to all non-indigenous people, regardless of skin color.

https://pages.ucsd.edu/~rfrank/class_web/ES-270/SimpsonJunctures9.pdf.

Bruce Albert and Davi Kopenawa, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, Bruce Albert and Davi Kopenawa (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2013).