For some people, economy is mostly about money. But that is stupid: economy is actually about something else. Money is just the medium conventionally assigned to all tasks understood as economic. In the end, money is just a medium. For all those who firmly believe that the medium is the message, this might resolve the issue. In general I tend to count myself among these late McLuhanians, but when it comes to economy, I beg to disagree. Economy is not about money. It’s about distribution. And at this task, money performs worse and worse, as we know.

This misalignment hasn’t served the art world badly so far, at least for a small chunk of it. Maybe in a near future we will learn to read much of contemporary art’s output as an undercover service to this weird cult of liquidity.

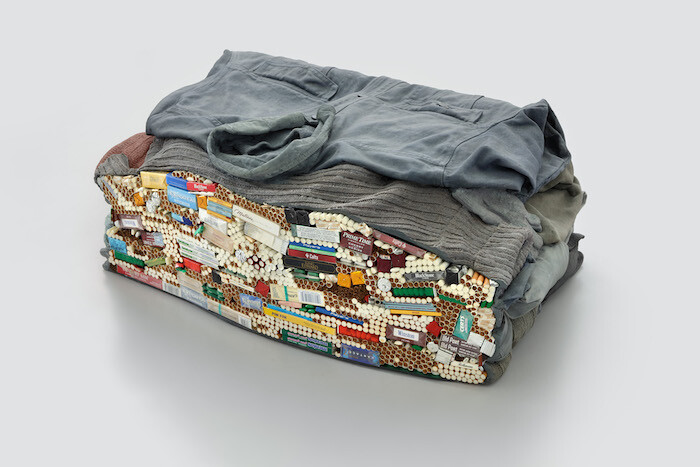

The group show “The Undercover Economist” is centered around a sculpture by Liz Magor, titled Carton III (2006). Seen from the entrance of the gallery, it looks like a pile of old workers’ clothes. Shoes at the bottom, some trousers, a thick woollen pullover, and a heavy gray shirt on top, all neatly folded. Now, as if carried from one place to the other, the order of the stack has suffered a bit.

According to writer and critic Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s theory of sculpture, one may read the pose of a figure always as a transitional moment in a movement. There is something pre-filmic in this theory, which he developed in his essay “Lacoön.”1 I can imagine a scene in which these clothes were handed to a rough sleeper at a charity. Shabby though they are, they’re still properly washed, then well folded, and handed out to someone, who took the pile and placed it next to his sleeping bag in a walkthrough. Then he used the clothes to hide another stack, one of cigarettes. The backside of the sculpture reveals that the clothes are covering a huge stack of cigarettes, and open cigarette packages. There are too many to be smoked by just one person. That means these cigarettes are meant to be distributed or to be given away or they are the result of some game of circulation. Given the fact that they’re all different brands of cigarettes, they may not come from the same source. They must have been collected. In this world, I cannot imagine a person who would collect such a variety of cigarettes. For that matter it falls on the observer, or should I say discoverer, to explore another world. A world in which this assemblage makes sense.

There are two or three other spaces of economic circulation in the show. First, next to Magor’s work, is a series of four oversized data cards, wrapped in colored felt by Gabriel Kuri: felt data card (2017). One carries a black stone, approximately the size of a human head. Two have shells stuck to the felt in patterns reminiscent of holes in a punchcard. One remains empty. We may read this series as a typology of money, with stones as tokens, like in Micronesia; shells that used to circulate as currency in many coastal places; and a void as in the space to write an IOU—as in our current form of money.

The second series, installed in the first room of the gallery, consists of three steel boxes, also by Gabriel Kuri—box for sort, box for stand, and box for and with (all 2017). They look like an interconnected system of distribution, associated with food. There are eggs, plates, salad leaves, straws, and a rotary brush-like tool. The longer I looked at these attachments, the more they looked like mere signs. Not like the real thing. As if these extensions are only there to make the metal blocks seem utilitarian.

The third series’ relation to economy is rather distant. Martin Boyce’s works Phantom Limb (Sister) (2002) and Dead Star (Sorrow) (2016) remain in the hermetic frame of the artist’s well-known references to modernist formalisms. They seem long frozen. They do not represent singular moments of movement, as in Lessing’s theory, but rather traces of an economic utility long past. Assembled around Liz Magor’s central piece representing an unknown economist performing his or her secretive circulation, all the pieces in the show refer to systems of distribution, some through tokens, others by signifying utility, or by tracing a functionality long lost. Do they link up to a whole? No, unless we would take them as a research collection of an undercover economist.

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing: Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766), in which he conceives a media-specific theory of visual arts versus writing starting from the Laocoön group, which was rediscovered in 1506.