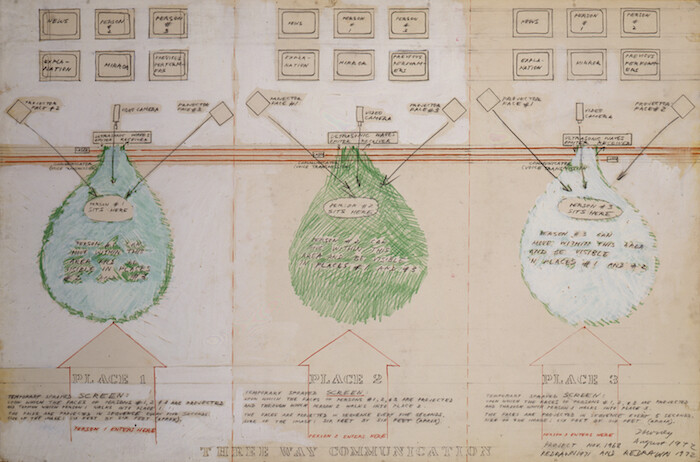

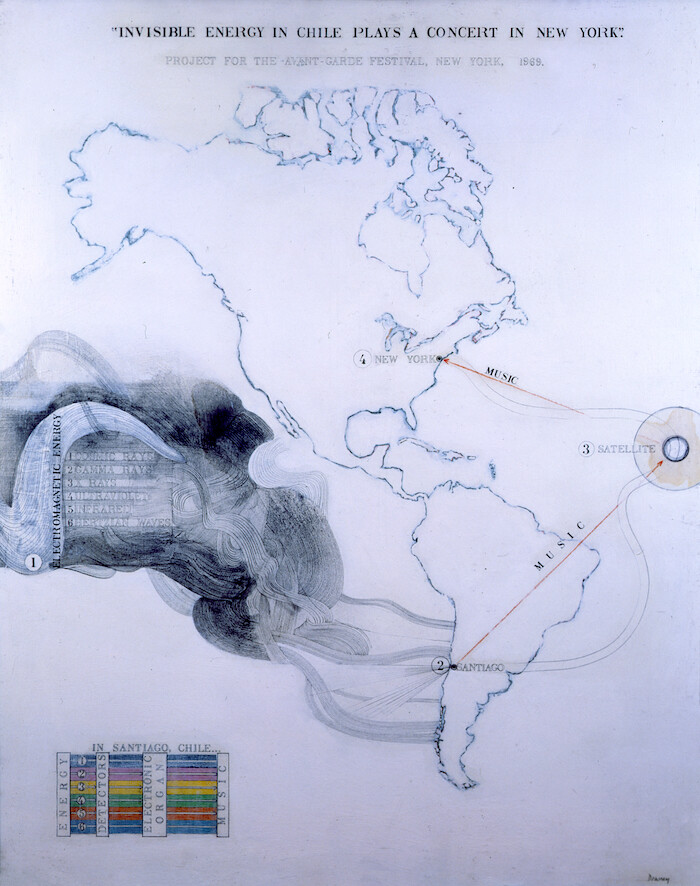

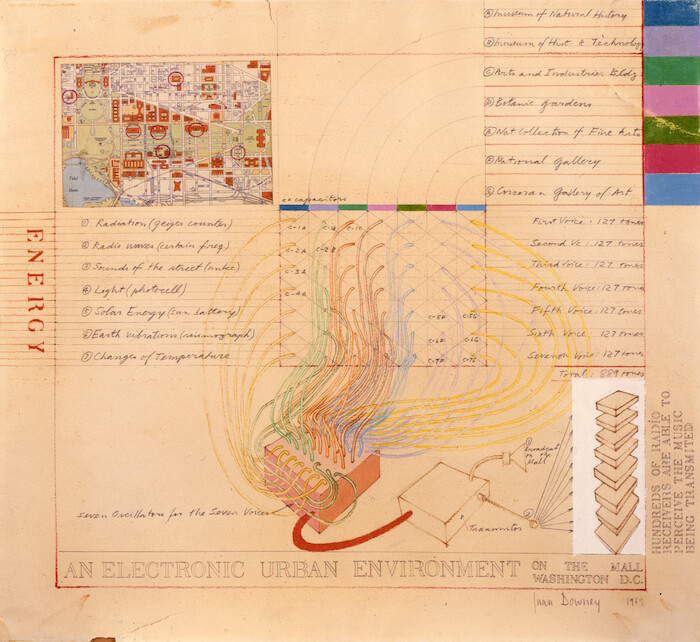

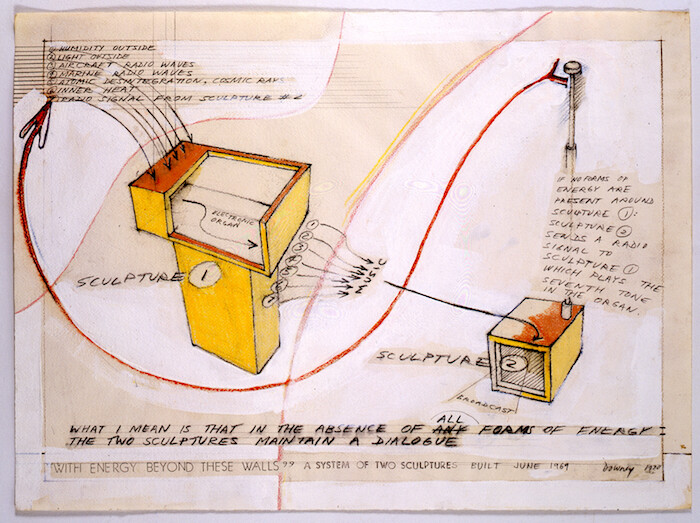

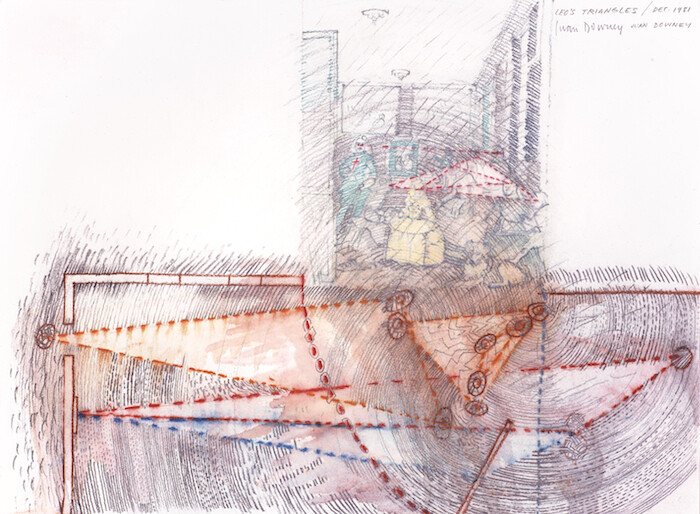

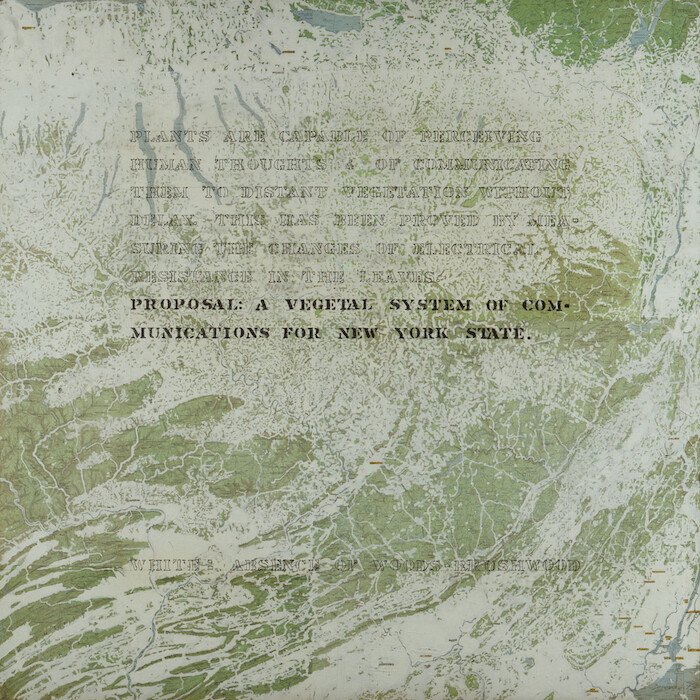

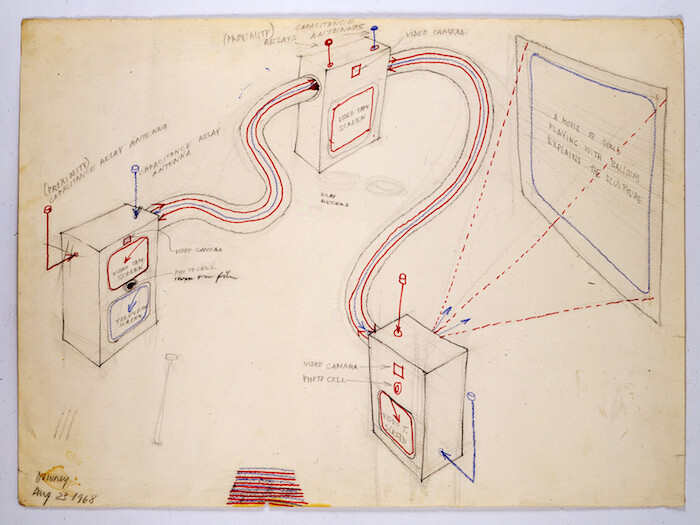

Juan Downey (1940–1993) has been recognized as an early pioneer of video art, but like many of his contemporaries, his interest was much broader than a single medium. Initially trained as an architect in Chile, where he was born, he traveled throughout Europe, meeting artists working with kinetics and interaction, such as Julio Le Parc and Takis. After moving to the US in the mid-1960s, he became a part of the discussion around the magazine Radical Software and associated groups that used early video technology to create alternative media channels. Downey’s own use of new technologies was often extremely speculative, exploring their potential to address and facilitate communication across space, between human and non-human participants, such as machines or plants. Presented in the Stockholm exhibition “With Energy Beyond These Walls” as a drawing, Three Way Communication by Light (1968–1972), for example, created a setup in which three participants in isolated rooms were filmed; the images of their faces, superimposed, were played back to the participants, engaging them in a loop of playful feedback. Downey saw electromagnetic signals, such as video or audio waves, as forms of “invisible architecture,” which create infrastructures. Invisible Energy in Chile Plays a Concert in New York (1969), also presented through a drawing, suggests such a structure through a direct link between two sites using audio signals transmitted via satellite connection. Unrealized by Downey himself, the proposal represents, in today’s satellite-driven and ultra-connected media reality, a standard of communication that somewhat lost its utopian appeal on its way to realization.

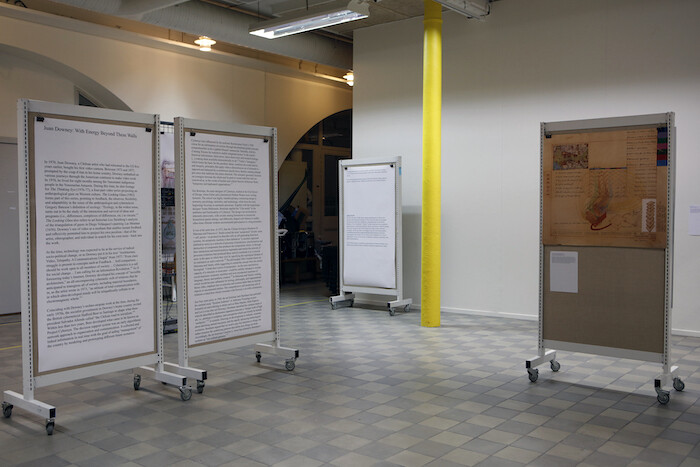

The exhibition is part of E2-E4, a year-long series of talks and events, organized by Stefanie Hessler together with Kim West and Lars Bang Larsen at the Royal Academy of Art, centered around early information theory and technology, and models of artistic self-organizing. With three single-screen video works and a selection drawings and collages presented entirely as reproductions and displayed on a system of movable walls, the exhibition is focused on the links between Downey’s work and its contemporary context, such as cybernetics and early conceptual art, and their aftermaths. These references are presented next to Downey’s works, sometimes literally in a spatial montage with short excerpts from texts and images, and an extensive selection of further materials. These include the history of the Chilean Project Cybersyn, a never fully realized electronic feedback and control system for Salvador Allende’s socialist government, designed by Stafford Beer and Tomaso Maldonado in the early 1970s; the work of Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, who understood organisms as autopoetic machines (a concept that reappears later in the writings of Félix Guattari); and Jack Burnham’s seminal essay “Systems Esthetics.”1 The exhibition points to a sensitivity that the American architecture historian Felicity Scott has described as a Techno-Utopia, in which technology became an agent—or a medium—of socio-political change, in the work of contemporaries of Downey, such as the collectives Ant Farm or Superstudio. Technology seemed to have the potential to organize the environment in a more responsive and adaptable way but also opened up possibilities to rethink the tools and methodologies of designers.2

The exhibition engages with the hope that new technologies enhance an understanding of our environment, but it also traces a shift from techno-utopian enthusiasm to a growing disappointment with the way in which technological advancements failed to deliver. Downey’s extensive travels through the Americas, in which he used the camera as tool to frame encounters, resulted in remarkable projects, for example with the Yanomami people in Venezuela. These works, such as The Laughing Alligator (1976–1977), one of the videos in the show and part of his “Video Trans Americas” series, talk about the social regimes and hierarchies that govern space and the gaze, and construct borders even there where technological barriers became redundant.

The space in which the exhibition takes place is itself a point of departure and a place of a historical experiment. Rutiga Golvet, the “checkered space” located in the building that today houses the Royal Institute of Art, was a project space of the adjacent Moderna Museet between 1971 and 1973. Called Filialen, it featured a program of events and presentations around critical social issues. Part of the program were exhibitions conceived as pedagogical tools, with image and text modules, produced at a fast pace and a low cost, which then traveled throughout the country. The space was conceived as a prototype for plans to rethink the museum as a high-tech information center modeled after the computer. These plans were stalled soon after in a process of moderation that led to the now existing Kulturhuset in Stockholm.3 The E2-E4 program as a whole, and the show of reproductions of Downey’s works, revisit this utopia of exhibitions that function as information nodes, to test its use today where we lack not so much access, but contexts to make use of information.

Jack Burnham, “Systems Esthetics,” Artforum 7 no. 1 (September 1968): 30-35.

Felicity D. Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics after Modernism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007).

For a history of Filialen, and the plans by a group of curators and activists around Pontus Hultén and Pär Stolpe to develop Moderna Museet into a new type of institution, see Kim West, The Exhibitionary Complex: Exhibition, Apparatus, and Media from Kulturhuset to the Centre Pompidou, 1963–1977 (Huddinge: Södertörns högskola, 2017).