A piercing whistle punctuates the blaring of a trumpet. But in the columned central space of the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, the only visible instrument is a grand piano. For three days a week throughout the course of the exhibition, the instrument is played—and, one could say, worn—by a pianist who stands in a hole cut into its center. Leaning over the rim of the piano to strike the keys, the performer energetically interprets the fourth movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (1824), while slowly pushing the wheeled instrument around the space. The building has become a musical box, the exhibition orchestrated so that one movement flows into the other, spilling through the gallery’s spaces to create a dissonant soundscape.

The piano of Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on Ode to Joy for a Prepared Piano (2008) could be thought of as the lead performer of Puerto Rico-based duo Allora & Calzadilla’s show. Popularly known as “Ode to Joy,” Beethoven’s piece has often been interpreted as a defense or celebration of humanist values, and in 1985 the European Union adopted it as its official anthem. Yet, as Slavoj Žižek has noted, the tune’s “universal adaptability” has made it vulnerable to use by disparate ideologies.1 In Nazi Germany, “Ode to Joy” was used to celebrate grand, nationalistic public occasions such as Adolf Hitler’s birthday in 1942, while during the Cultural Revolution in China it was considered an example of the bourgeois culture of the West. This malleability should prompt us to be skeptical of the anthem’s political significance, especially in light of the questionable values the EU has demonstrated during the refugee crisis alone.

Allora & Calzadilla have long explored the cultural and political dimensions of acoustics. Their first solo exhibition in Spain duly focuses on sound and its connections to geopolitics, through various human and non-human encounters. Wake Up (2007) is a sound and light installation comprising a freestanding white wall, in which lights flash and military trumpets bugle intermittently into the central space. The whistle-blowing sounds, meanwhile, emanate from the upper floor, leading the viewer to the gargantuan form of a loafing hippopotamus made from dried mud. In Hope Hippo, which premiered at the 2005 Venice Biennale, a performer sits atop the beast while reading the day’s newspaper, blowing a whistle whenever they read about something they consider an injustice.

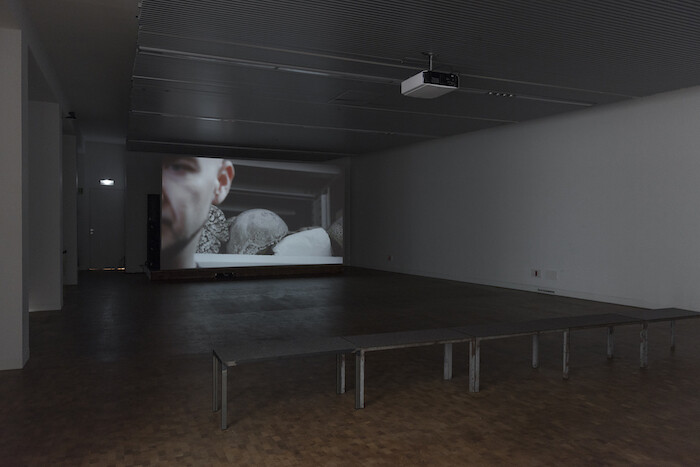

At the opposite end of the sonic spectrum is Apotomē (2013), a 23-minute video featuring Tim Storms, a vocalist who holds the world record for the lowest note produced by a human voice. Storms sings an extraordinarily low version of a melody originally performed for two Sri Lankan elephants brought from Holland to Paris in 1798 as spoils of war. The shaman-like singer navigates the storage of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, where the bones of the elephants are stored, performing his guttural lament.

Despite the focus on Puerto Rico in the texts that accompany the exhibition, only two works directly engage with the artists’ home. The video Sweat Glands, Sweet Lands (2006), displayed on a monitor near the terrace, shows a pig being roasted over an open fire to an infectious reggaeton soundtrack. Puerto Rican Light (Cueva Vientos) (2015–17)—a project that displayed the titular 1965 neon sculpture by Dan Flavin, which consists of red, pink, and yellow tubes intended to evoke Puerto Rican sunsets, to a remote limestone cave in a forest near San Juan—offers a deft art-historical comment on postcolonial migration and displacement in the US territory. But The Night We Became People Again (2017), a video that documents the dark, dank cave in which Puerto Rican Light (Cueva Vientos) was displayed, pairing footage of natural light shafts and flickering bats with a brooding drone-music soundtrack, will only be screened in Barcelona during a seminar about the legacy of the piece in the aftermath of the 2017 hurricanes.

At the Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Lifespan (2014) is at once the most subtle and the most potent work, offering a nuanced comment on the destructive natural forces that have devastated Puerto Rico. A 4.5-billion-year-old rock fragment appears to float mid-air, hung from an invisible thread from the ceiling. Each Thursday evening, three musicians gather around it for around fifteen minutes, their breaths, puffs, whistles, and whispers swaying the Hadean rock slowly back and forth. By effecting a micro-scale weathering process, in real time, with their own humid winds, the performers imbue the Anthropocene epoch with the intimacy of human consciousness—the pre-Socratics described the soul as pneuma, or breath.

The sparse display of the show, which places emphasis on durational pieces, is daring. As with the grand piano in Stop, Repair, Prepare, performative elements may not be “on” during a casual visit. Originally produced for Documenta 13, the video Raptor’s Rapture (2012)—in which the musician Bernadette Käfer plays a 35,000-year-old flute carved from a griffon vulture’s wing bone, producing harsh, wheezing whistles as she explores the flute’s tonal qualities—will be shown for a week at the city’s Palau de la Música concert hall. Despite the slow curatorial mood, which feels closer to Dia Art Foundation in its heyday in New York’s Chelsea, this exhibition-as-program is a poignant symphonic experience, in which performers and instruments, both ancient and modern, breathe life into the building.

Slavoj Žižek on Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” in The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XM9erS90gTE&.