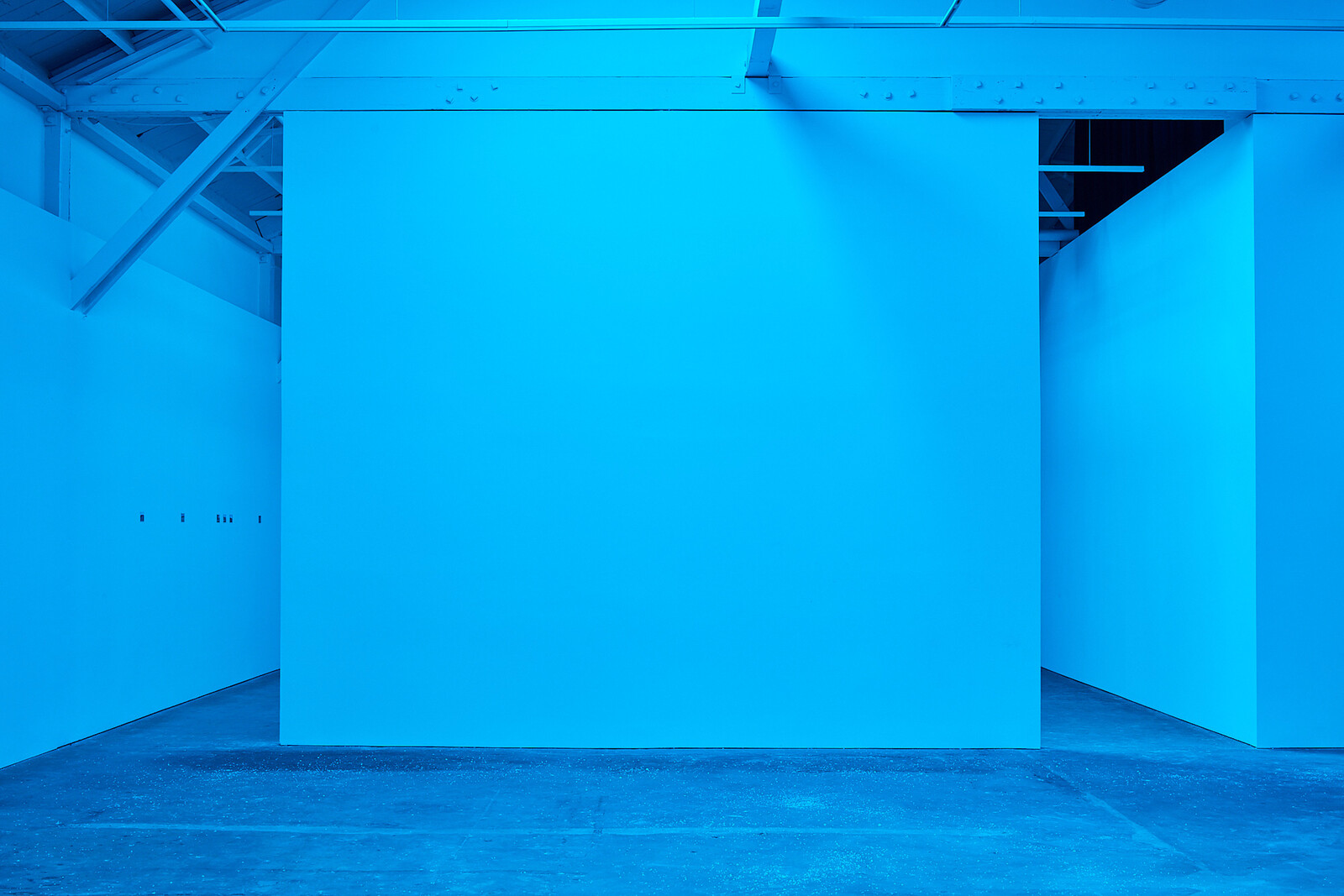

The second time I visited Lydia Ourahmane’s exhibition I was alone save for the young student-docent sitting at the front desk wearing earphones. Standing in the cavernous, quasi-industrial space—most of the internal walls had been removed—it felt appropriate that the last show I expected to see in a long time should be a near-empty room flooded with blue-tinged light (the front windows and skylights are laminated in sheer cobalt film) in which two tape decks mounted on opposite walls play recordings of an opera singer holding one note, and then another. The exhibition took on an elegiac air; the sung notes—a spare, tonal fabric—assumed the weight of lamentation.

This cyanic atmosphere reminded me of visiting Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s retrospective at Paris’s Centre Pompidou, a few days after the citywide attacks of November 2015, through which played a soundtrack of rain. I read the recorded deluge as an aural landscape of mourning, a kind of liquid dirge. That the current climate of fear has been triggered by something invisible to the naked eye—a viral “parasite” so minute that 50,000,000 could fit on the head of a pin—feels germane in the context of an exhibition made by an artist who prizes the ineffable, the unseeable.

The central work, the titular Solar Cry (2020) (its name derives from Georges Bataille’s 1930 text “Rotten Sun”) is in fact invisible, a sound work that uses eight transducers and four amplifiers embedded in a wall to play, at a frequency that registers more as a feeling than a sound, a recording of 87 minutes of “silence” that Ourahmane recorded on the desert plateau of Tassili n’Ajjer. The Saharan landscape of this national park at the southeastern edge of Ourahmane’s native Algeria is so famously inhospitable that even the military has been unable to gain an operational foothold there. To make the recording, Ourahmane sheltered within a cave whose interior is inscribed with prehistoric drawings and glyphs (dating back 12,000 years to when the area was a lush savanna). To “hear” it, one must press one’s body against the wall and allow the sound to reverberate through the bones—it can scarcely enter through the ears; it must be felt.

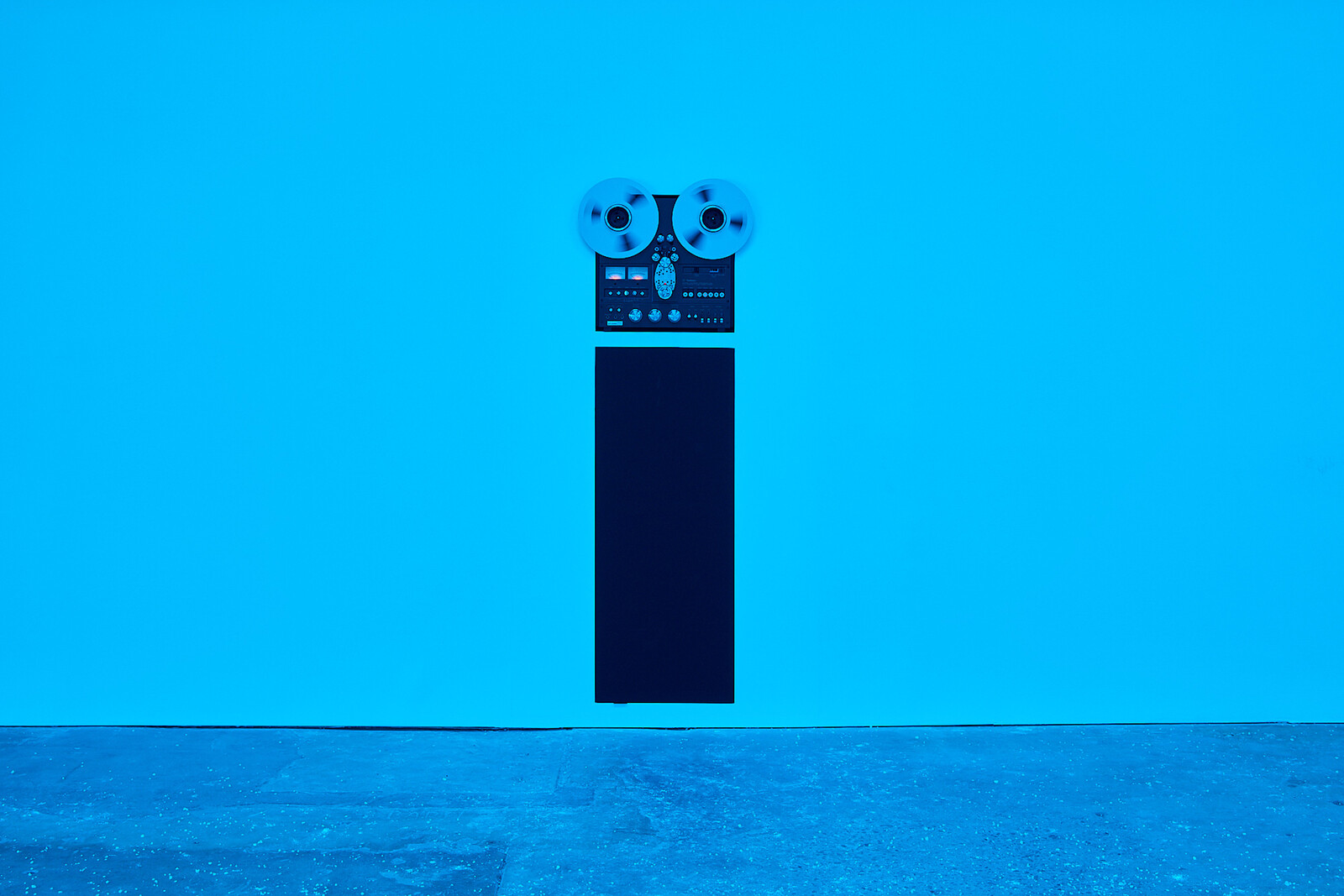

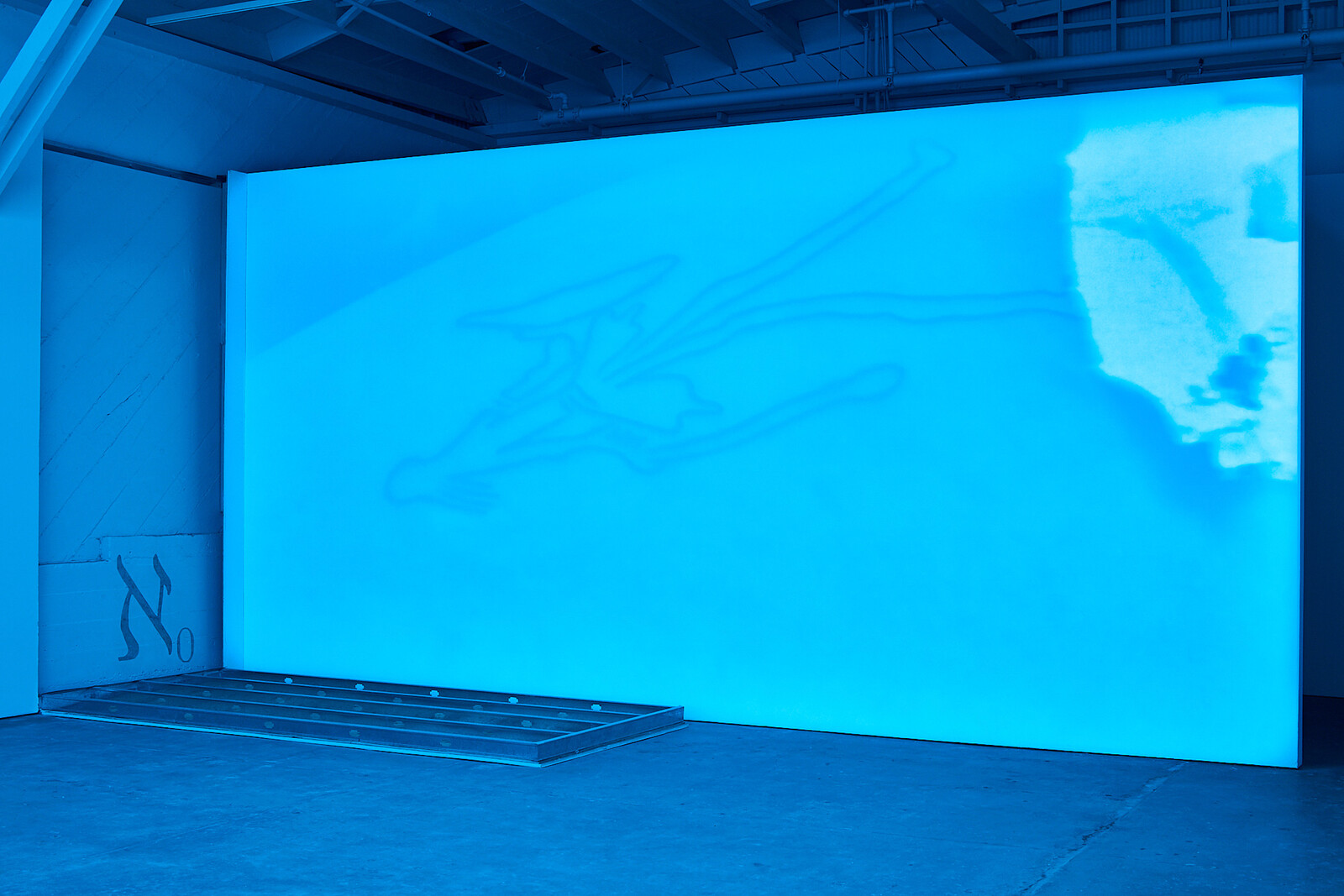

The whole of Ourahmane’s exhibition is a layered thrum: the melancholy duet that greets you; the crunch of three kilograms of crystal salt spread underfoot (3kgs salt, 2020); the sinister purr of a tattoo gun (the buzzy soundtrack to a bleached-out film projected in the back gallery showing the execution of a tattoo—the recipient, whose face is out of frame, is Ourahmane herself); the fluctuating whine of a metal detector, Gold Digger (2020), crying out to a gram of gold embedded in the concrete floor beneath it. “Solar Cry” is embroidered with longing for something or someone just out of reach. The two notes of Ab, Bb (2020), for instance, strain across an expanse to hold one another—a single step separates them on the musical scale, too slight a distance to allow them to converge in harmony. Nikola Printz, the mezzosoprano who recorded the two notes, did so in situ, instructed by Ourahmane to sing each note continuously for an hour. The very humanness of the instrument becomes its failing: as time wears on, the voice falters, grows tired, unfocused, degrades. Likewise, the tape in the recorders wears down with the passage of time, as the soft copper plates used to make etchings are gradually eroded by the pressure of the process.

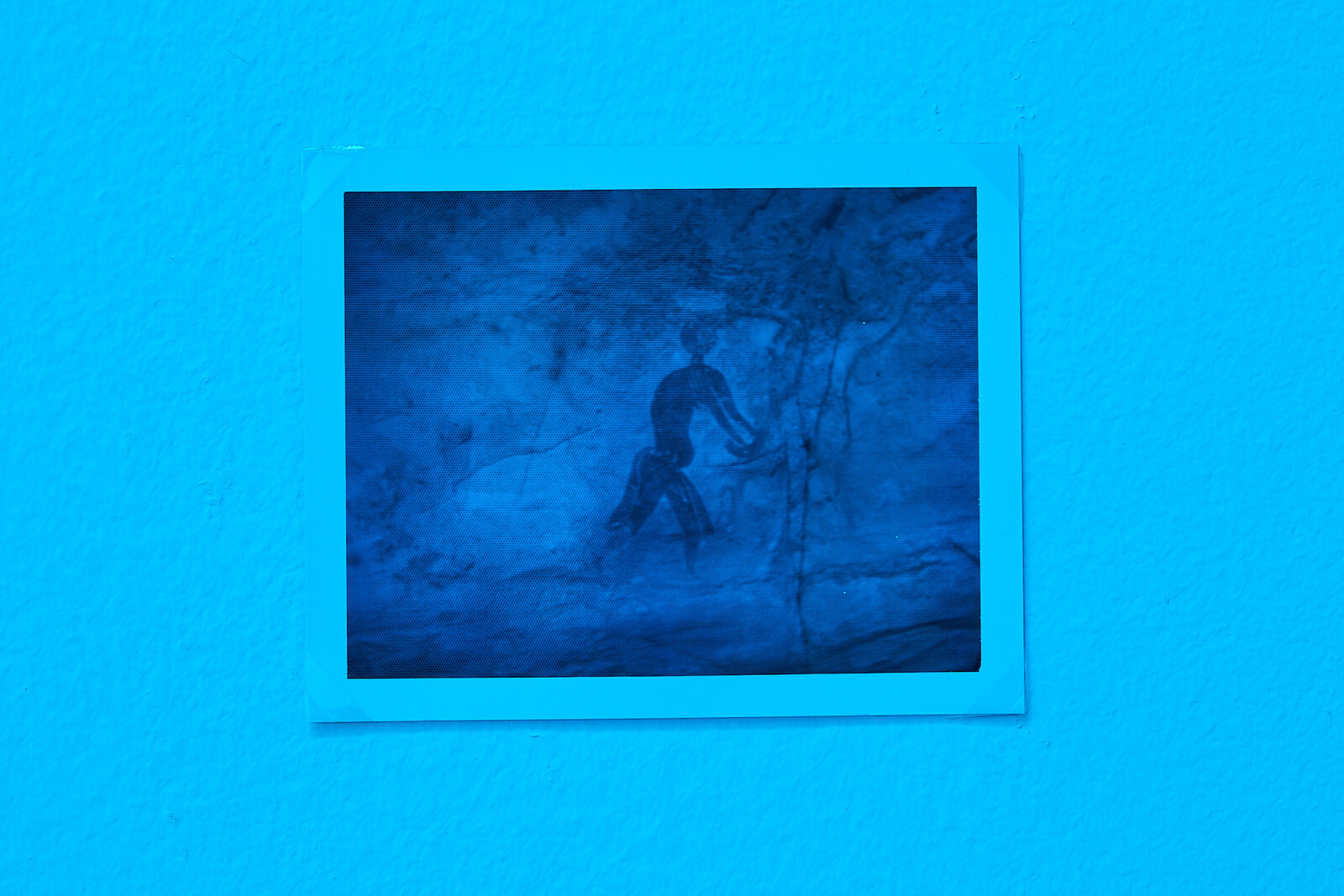

Etching is another leitmotif here: in the back gallery, a section of drywall lies flat on the floor, plaster face down. A slice of exposed concrete—the load-bearing bones of the building—can be seen in the space from which the section has been excised. Onto this surface Ourahmane has etched an “aleph-null,” the mathematical symbol for infinity (the aleph symbol is also the first letter in the Aramaic and Hebrew alphabets, and is said to originate from an ancient Egyptian hieroglyph of an ox’s head—a call-back to the cave paintings that garland Ourahmane’s recording of silence). The etching will remain long after the exhibition closes, sealed behind the gallery wall, entombed in its drywall sarcophagus. So too, will the etching of a prehistoric drawing of a warrior girl that Ourahmane has had tattooed onto her flesh (a crude shape not unlike the aleph-null); the tattoo was performed at the oldest tattoo parlor in Spain, the color of its ink matched to the pigments used in the cave. This is not the first time Ourahmane has transformed her body into a site for her work; a gold tooth (one half of the piece In the Absence of Our Mothers, 2018) is implanted in her jaw.

These interventions both taunt and collapse time. When Hiroshi Sugimoto began photographing the sea in the early eighties, it was with the intention of capturing a subject that could plausibly have looked the same 50,000 years ago: a view shared with primordial man, a view impervious to time. A similar impulse is at work in “Solar Cry,” in which Ourahmane is striving—via whatever tools and materials necessary—to communicate across history. Her dogged pursuit of the eternal is a full-throated cri de cœur.