Earlier this summer Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt launched a multi-part tribute to Umashankar Manthravadi, a Madras-born journalist, poet, and pioneer of acoustic archaeology. “A Slightly Curving Place,” an exhibition curated by Nida Ghouse, ran from July to September and featured audio and video installations inspired by Manthravadi’s work; it was complemented by “Coming To Know,” a discursive program co-curated by Ghouse and Brooke Holmes that unfolded over the course of the exhibition. These two projects are joined this fall by the publication A Slightly Curving Place. Edited by Ghouse in association with Jenifer Evans, and the first in a planned series titled “An Archaeology of Listening,” the book features scripts, scores, sketches, and essays that elaborate on questions posed by the exhibition. (The second volume, co-edited with Holmes, will follow in spring 2021.) What does it mean to listen to the past? Why does a Maya pyramid or an Udayagiri cave sound the way it does? And how can listening to historical sites help us unlearn archaeology as a discipline that colonizes the past by collecting it for display?

Manthravadi began working in archaeoacoustics—in which archaeological sites are mapped and measured according to their acoustic properties—in the 1990s. He developed his own ambisonic technology on a shoestring budget to map ancient sites, such as the second-century theatre in Rani Gumpha, Odisha, and for the past 33 years has been based at Delhi’s Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology. Three vitrines at the entrance to “A Slightly Curving Place” displayed objects and materials referring to the recording and transmission of sound: wax, shellac, and vinyl; a galena crystal radio; and various drawings and publications. In the main foyer, a commissioned video work by dancer and choreographer Padmini Chettur and composer Maarten Visser relied on the body as recording device to trace the transplanted archaeological site of Anupu.

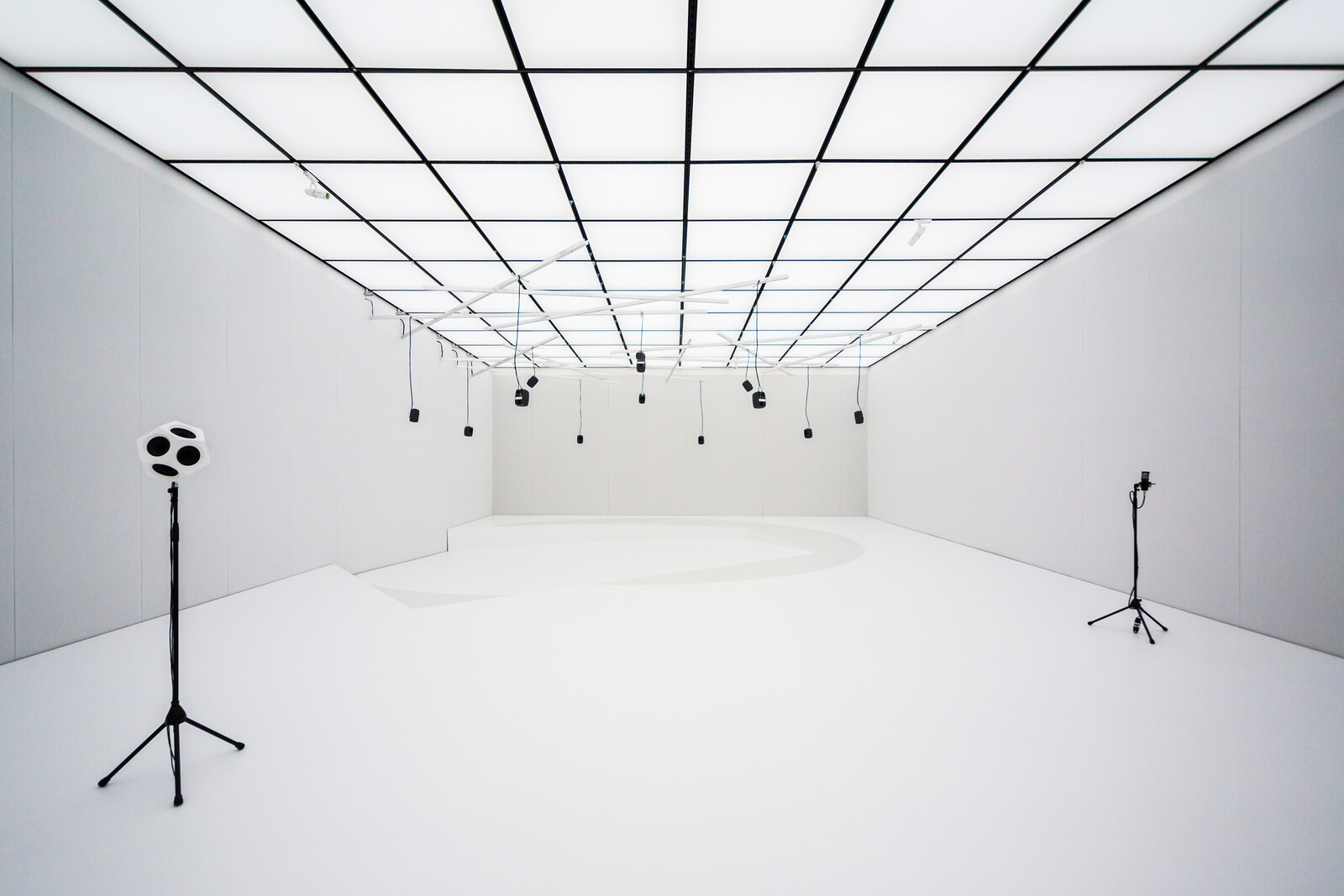

At the center of the exhibition was an ambisonic dome in which thirty loudspeakers, hung from the ceiling and hidden inside the walls, emitted a 90-minute sound play. The outcome of multiple conversations and collaborations over several years, each of its eight chapters was narrated and produced by a group of contributors who approached sound variously as matter, meaning, and music. The auditory setting turned the exhibition into a communal experiment, in which visitors listened to the act of listening itself. The online public program “Coming To Know” built on the collaborative and interdisciplinary spirit of the exhibition. A dozen international artists, researchers, scholars, and writers—from fields including anthropology, music, literature, and sound art—convened in three online sessions to discuss digging, recording, and tuning. That many had collaborated on the exhibition gave the participants a shared familiarity as they dug into epistemic technologies of listening, and reflected on archaeology’s ocular bias and the impulse to colonize the past. The more I listened, however, the more I felt the separation between lived practice and its academic afterthought.

The exhibition provided space for a sensorial understanding of the ideas at stake, and the virtual public programme created an equally rich environment in which to discuss it; A Slightly Curving Place continues both strands’ attempt to bridge the divide between archaeoacoustics as craft and technology, and the more philosophical questions it raises. But what remains productively unsettled within the collective listening situation of the exhibition and online event cannot echo in the same way in a printed publication. As a result, the book lacks cohesion and the link to Manthravadi’s life and work is not always clear.

His autobiographical essay—plain and simple, yet informative and entertaining—feels disjointed from the book’s eclectic mix of voices and styles, including essays, transcripts, and anecdotes that range in tone from the scientific to the poetic. The scripts of writer Alexander Keefe’s “Site VII A” and the wonderful “Burrowing” by singer and writer Moushumi Bhowmik, of the nomadic field recording collective The Travelling Archive, evoke the rich listening experience of the exhibition. “The Book is Drenched” by Vinit Agarwal, meanwhile, traces voices inscribed in lettered tattoos and the sounds that are lost in the transitions between dialects and alphabets.

After reading the book, listening to nine hours of talking heads, and sitting several times through the 90-minute composition in the show, the elements begin to come together. The more I sensed things falling apart, the more I wanted to listen to all of it over again. The exhibition, live events, and book feel coherent when considered as a whole because of the productive fluctuation and dissonance between the three formats. Ghouse, Holmes, and their collaborators are never didactic, nor do they alienate. In keeping with the spirit of cross-disciplinary tribute to Manthravadi, A Slightly Curving Place allows listeners and readers to develop a logic of their own—so they keep asking themselves how they got (t)here.

Ghouse cites as inspiration the introduction to Phiroze Vasunia’s The Classics and Colonial India (2013), which references Homi Bhabha’s application of Jacques Derrida’s notion of a demand for a narrative to the British colonizer who insisted that Indians reveal their history: Tell us what happened. Tell us why you are here. In turning the colonialist’s demand around, Bhabha reveals its implicit threat: Tell us why we are here. In the same spirit, this is not a book about Manthravadi but one with him, refusing any such demand.

An earlier version of this review listed the book title as An Archaeology of Sound. Following a new decision by the book’s editors, and at HKW’s request, we updated the review to reflect its new series title of “An Archaeology of Listening,” of which A Slightly Curving Place is the first volume.