In his 1931 essay “Unpacking my Library,” Walter Benjamin describes unboxing his collection of books in a single day, working without stop from noon until past midnight. Months after moving house on the first day of Berlin’s lockdown, I’m still working on mine; my books are, as Benjamin would say, “not yet touched by the mild boredom of order.” I’ve been slowed by a desire to read these exhibition catalogs, artist books, and hybrids of the two. With no opportunity to visit IRL art spaces, and overwhelmed by digital “viewing rooms,” my catalogs became my galleries and institutions.

The process reminded me of my earliest brushes with fine art, the pictures in my mother’s Art History textbooks (including a vintage mid-1960s edition of H. W. Janson’s History of Art) when I was a kid in rural America with no access to the real thing. The books in my own collection are artifacts of events I attended, and others I wish I had. They are historical documents, discursive platforms, snapshots of zeitgeists. They are windows or deep dives into artists’ practices, the infrastructures of exhibitions, and the thoughts supporting, diverging from, and swirling around art and all its mechanisms. And some of their many roles unfold only long after the exhibitions they document close.

Benjamin connects each book to recollections of how he acquired it, but my strong memories are generated by how the internal “spaces” of the pages connect to the exhibitions they complement. Touching the paperback cover of the survey catalog of MoMA’s collection I acquired in the early 2000s, when the museum temporarily moved to vast warehouses in Queens during an expansive renovation, not only reminds me of seeing the 2003 “Matisse Picasso” show in those antiseptic, hangar-like halls, but also of walking through “Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism” (1989–90) in the old, low-ceilinged MoMA when I was a student from the backwoods.

Unlike Benjamin, I don’t collect catalogs; they seem simply to appear, given to (or thrust at) me by press departments, the publishers and institutions I work for, artists I may not have heard of or met.1 I have fewer than I once had, having moved too often in the past half-decade, but I know that the empty corners in my difficult-to-equip new attic flat—with sharply slanted walls and high beams—will soon be colonized by future exhibitions and the books that immortalize them.

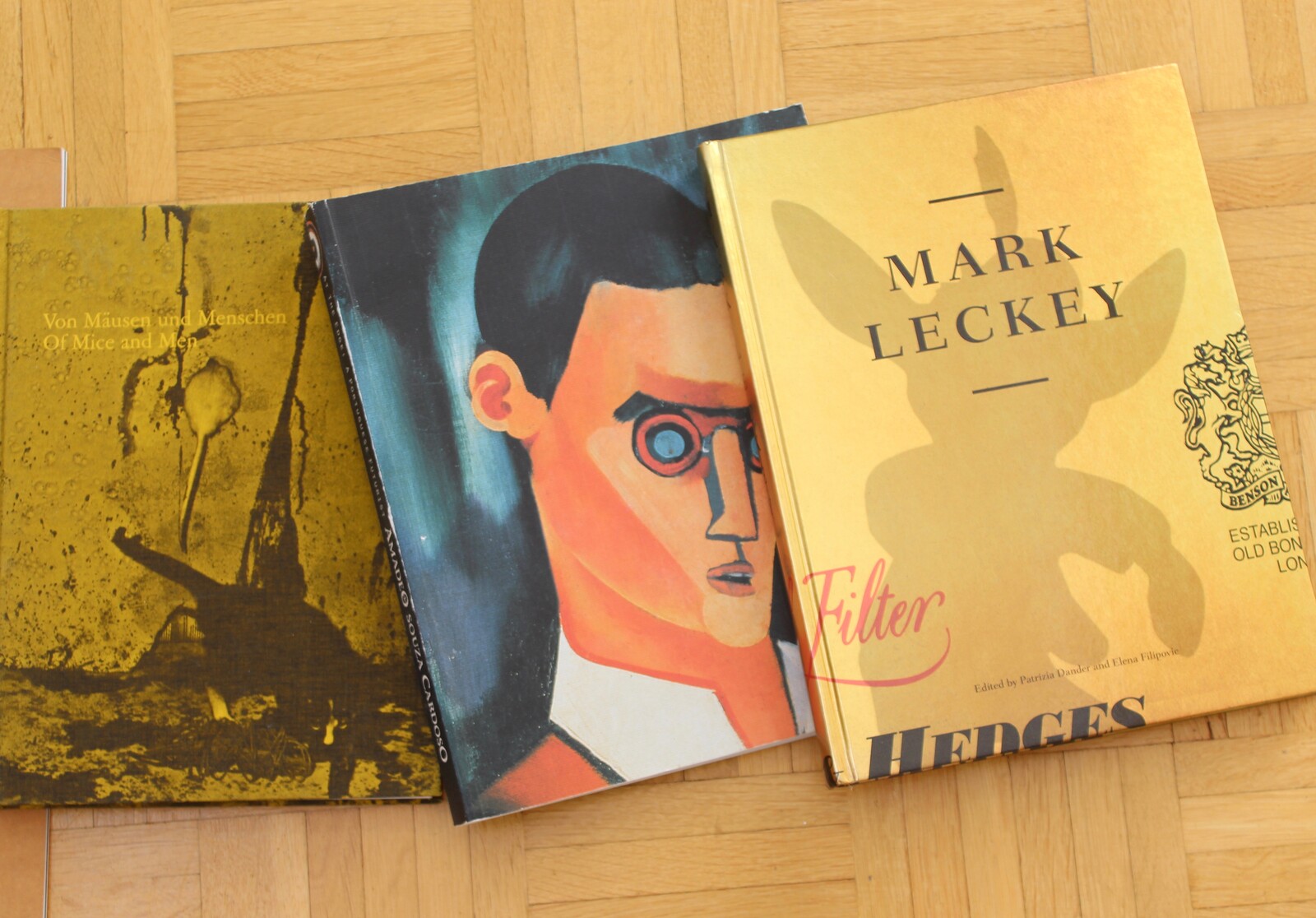

Early examples of the form—the first appeared alongside the Paris Salon of 1673—were primarily taxonomic, mere listings of works on view, but over the centuries have evolved into today’s research- and theory-driven tomes, with their snappy interviews and sexy covers. An eye-popping example of the latter is connected to my first-ever review, of Amadeo de Souza Cardoso at New York’s AXA Gallery in 2000. The pages inside this large-format paperback, with textured cover and jaunty spine, are smattered with fabulous color pictures interspersed with double-spaced text. Three moves and five years ago, my partner, an artist, urged me to toss it, then became absorbed in its colorful, unfamiliar images and essays by mostly Portuguese writers. The book is still with me; the partner is not.

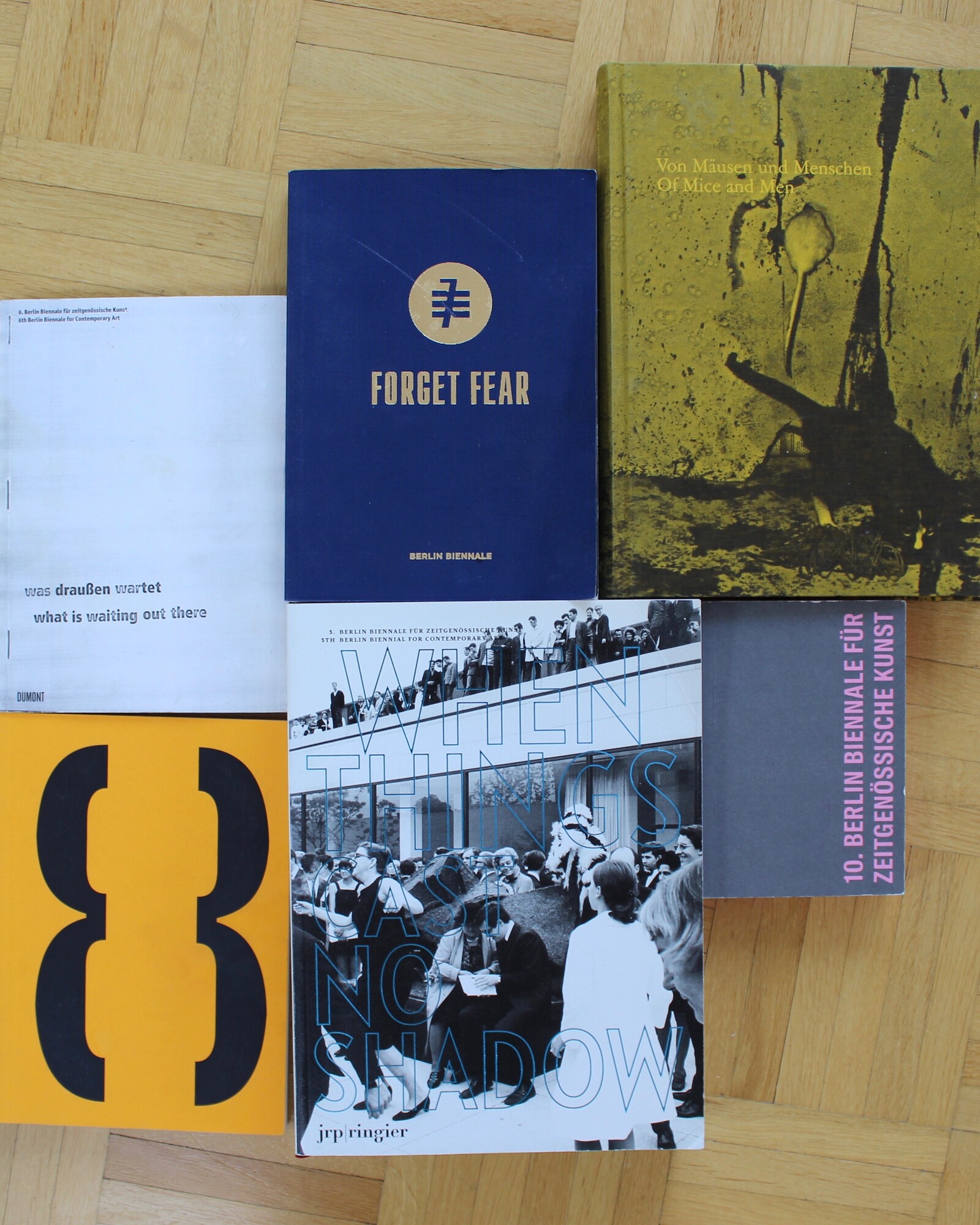

A box of catalogs from the Berlin Biennials, dating from Ute Meta Bauer’s 2004 edition (the first I attended), traces the stories of post-Wall gentrification, shaping and expanding its collective cultural memory. As Berlin’s art ecosystem has become less about the local East/West binary and more about the global North/South, the books have become increasingly discursive. Other biennial catalogs—from Manifesta, Marrakech, and Athens2—are as dense with theory as cultural readers. The format makes sense as an opportunity to communicate the intellectual underpinning on which thematic shows depend, especially given that they are usually produced prior to the exhibition (making it impossible to include installation shots). The exception is the Venice Biennale, whose catalogs stick to the early taxonomic format—a matter of sheer scope, perhaps.

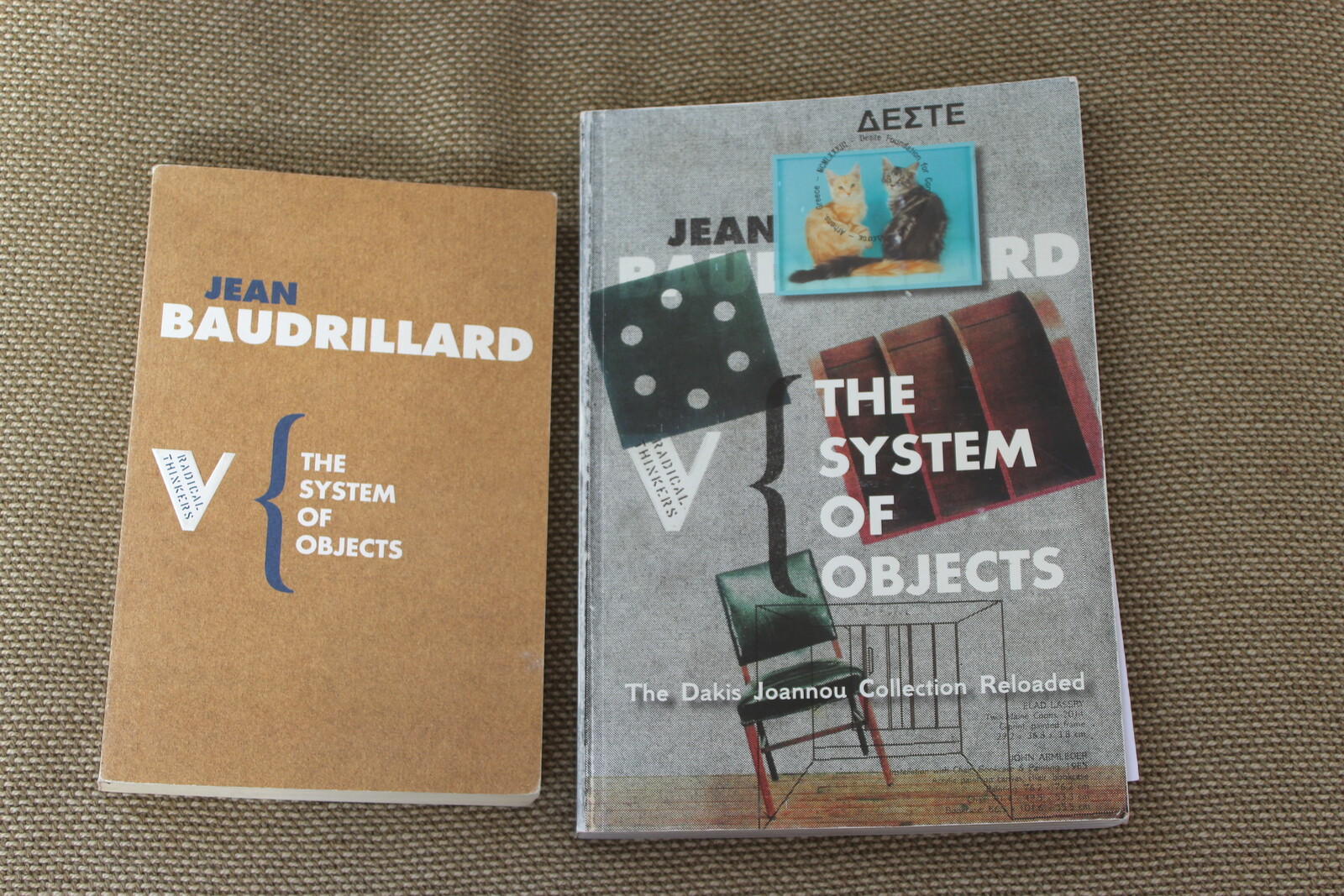

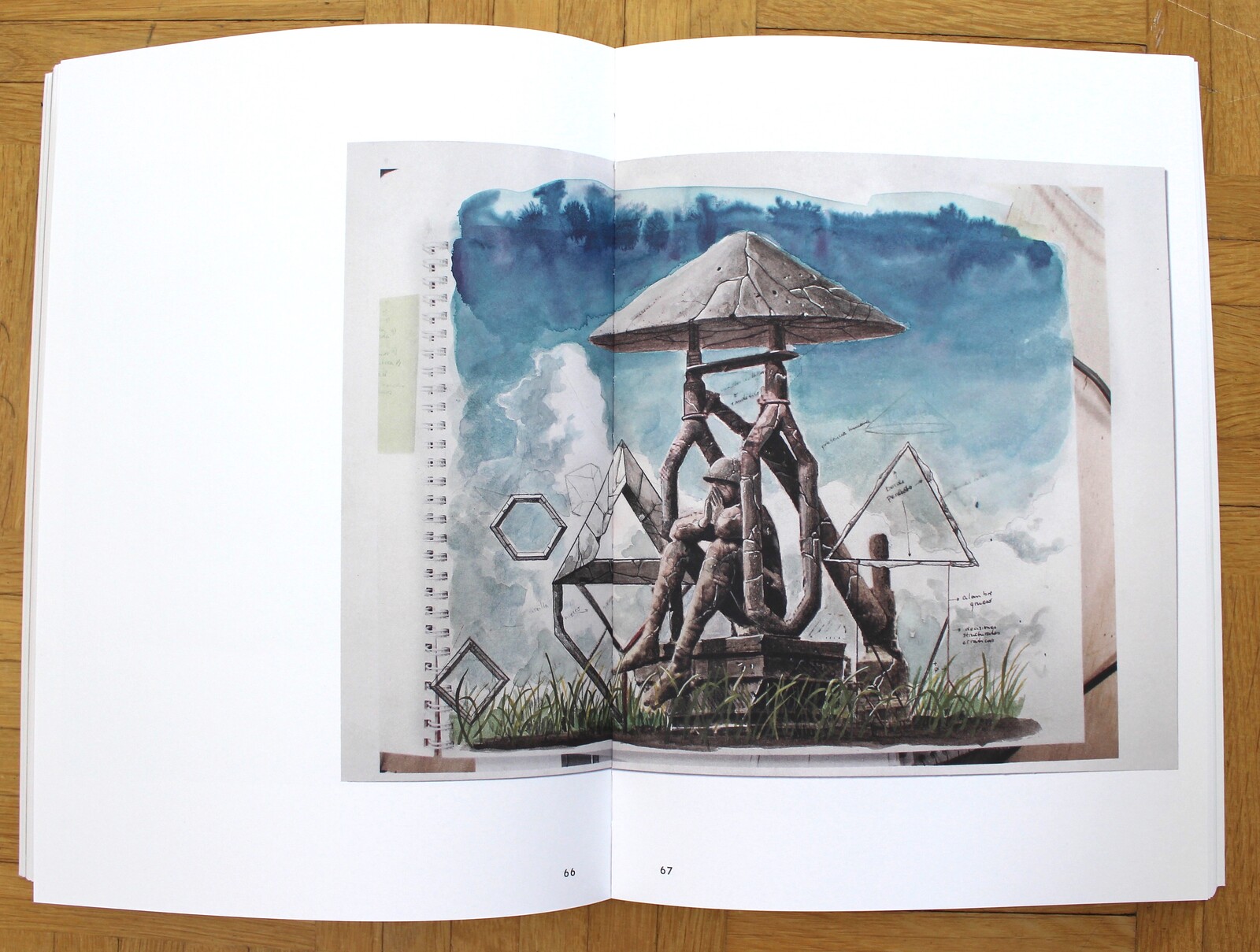

The recent standardization of exhibition catalogs—an introduction, between two and four essays, an interview, pictures of art, a works list—makes more experimental takes all the more refreshing. Andreas Angelidakis’s journal-sized The System of Objects, a 2013 recast of Dakis Joannou’s collection in his Deste Foundation space in Athens, is one example. On each page, a foggy installation shot is superimposed over hazy text from the curator’s “beach copy” of Jean Baudrillard’s eponymous book, like a double-exposed roll of film. Yto Barrada’s staple-bound The Sample Book, accompanying a 2016 exhibition of the same name at Vienna’s Secession, with its embossed, International Klein Blue fabric cover and odd vertical orientation, is another example. Adrián Villar Rojas’s catalog for a 2013 show at Museum Haus Konstruktiv in Zurich shows few of the works on view, preferring to present the drawings that led to them, offering a peek into the artist’s mind and processes.

All of this begs the question: what is the exhibition catalog for, now that museums are rethinking their missions, and most of us are travelling less? Even before the pandemic, cash-strapped US institutions were moving towards online blurbs, print-on-demand “catalogs,” or no publications at all. Could the exhibition catalog in its established form die off? I hope not, because I—like so many others—treasure the best of these books not only as research materials but as substitutes for encounters with art in three-dimensional space.

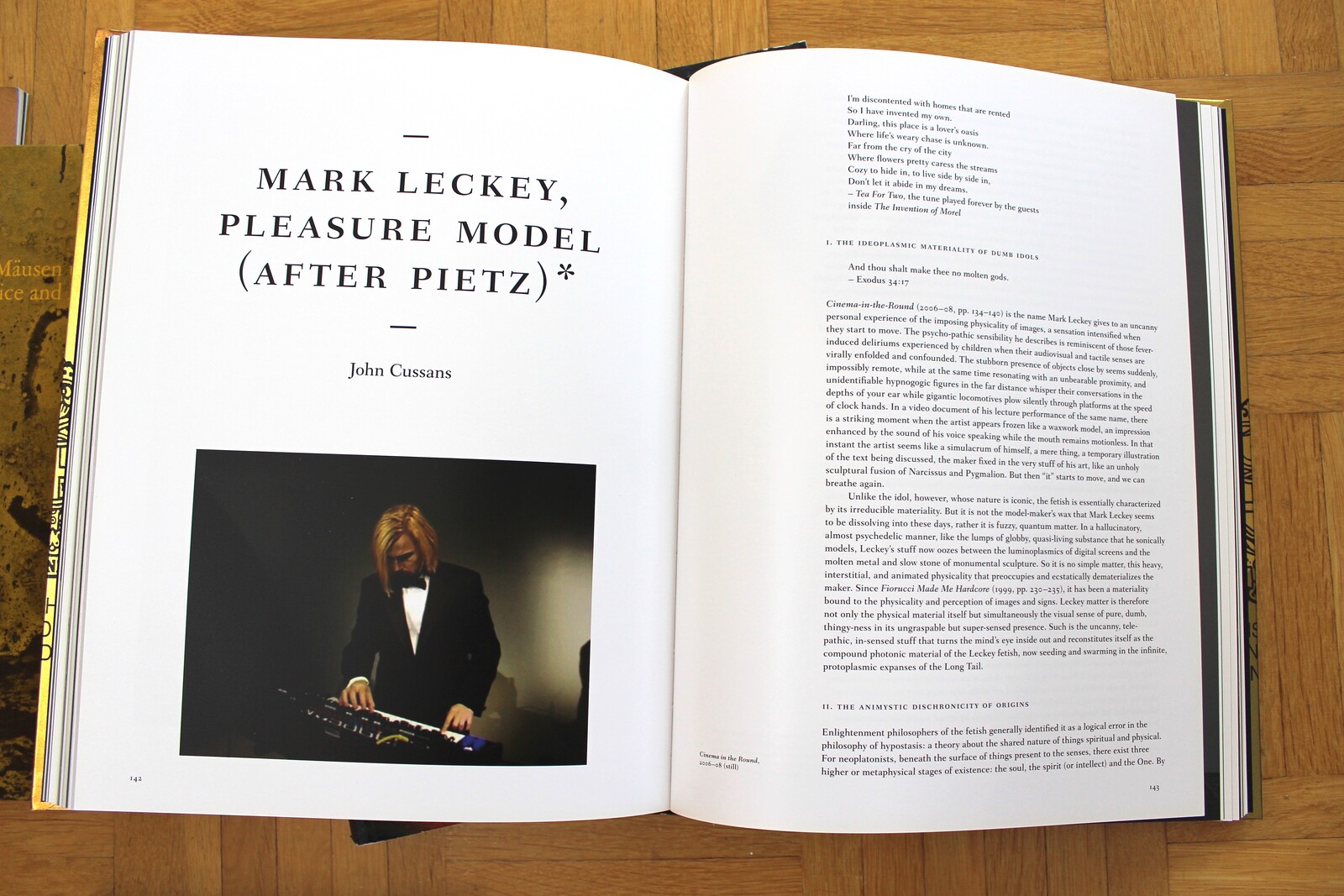

During the most isolated weeks of lockdown, that consolation was of paramount importance to me. It has also been intriguing, returning to them, to observe the passage of time and progress through their texts and images. More than ten years after obtaining a small catalog produced to accompany a 2008 show by the Prague-based artist duo Anetta Mona Chişa and Lucia Tkáčová at the artist-run space n.b.k. in Berlin, to take one example, I realize that the duo were talking about many of the problems that would erupt in the #MeToo and #notsurprised movements, and in late capitalism in general. It’s only looking back on Mark Leckey’s On Pleasure Bent (2014) that I can understand the artist’s significant place in the exhibition history of the 2010s.

In some cases, a catalog is the only record of artistic production: memories can be short, and evidence lost or “disappeared” far more quickly and easily than one would think. Last year I saw an extraordinary show at the Lower Belvedere in Vienna: “City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna from 1900 to 1938.” In the first decades of the twentieth century, Vienna’s female artists were productive, emancipated, and visible, showing in avant-garde galleries and, after 1920, attending Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts. But many of them were forgotten during and after World War II: some fled or were killed, and their artwork vanished. The curator, Sabine Fellner, told me that the only way she could identify important protagonists and locate the works was through the very few catalogs that had survived from the period. Within the exhibition, one lost but seminal work was pictured only as a page from one of these catalogs. Sometimes, artifact becomes fact.

As museums and galleries reopen, I go out into the city to look at work again. But I’m also spending more time at home, reading and arranging my library. The books are out of their boxes, but still finding their places. The mild boredom of order may never arrive.

In some European countries, artists produce an almost alarming number of small catalogs paid for by their generous governments, something of which American artists—who depend more on galleries or collectors for such things—can only dream.

Kimberly Bradley reviewed the 6th Athens Biennale for art-agenda in 2018: https://www.art-agenda.com/features/242226/the-6th-athens-biennale-anti.