May 13–November 26, 2017

There was widespread suspicion about “Viva Arte Viva” even before Christine Macel’s 57th Venice Biennale opened last week. This year’s edition fell short of gender parity with almost two-thirds of the participants male, fomenting heated critiques on social media upon release of the artist list. Racial metrics were worse; case in point, five of the 120 artists are black. These are normal problems for the Biennale (even if the upheavals of the past two years have shone a spotlight on them), though they remain audacious statements for an institution meant to be representative and contemporary. Even more audacious, some might say, is the absence of a thesis engaged with anything more than the nominal boosterism of art itself as a proxy for humanism.

The morning of the press preview, I checked Instagram and saw that perennial truth-keeper Frances Stark (@therealstarkiller) had shared a still from a video concocted for the Biennale’s website, noting in the caption that it was “made under duress to contribute promotional material” to the show. In the same post the artist wrote she was “uncomfortably in the dark about this year’s Venice Biennale,” unaware of where or how her work (on loan) would be shown. This echoed sentiments of other artists I spoke to, less inclined to put institutions on blast. (Stark’s painting was installed in a hallway in the Giardini, part-framed and part-obstructed by a doorway.)

While hardly breaking news, this story did not jibe with the slogan of: “a Biennale designed with the artists, by the artists, and for the artists.” Maybe those who made large commissions were more intimately involved; the artists are probably treated differently according to their priority. Things like this being accepted as part and parcel of mounting a big international exhibition should raise questions about the extent to which they’re actually good for artists, or consequently for art. In small ways this mirrors some of the power dynamics giving way to populist revolts—the tectonic history-in-the-making which has been largely passed over in the framing of this show. There is a more cynical reading of Macel’s condescending Gettysburgian promise: that the artists will be put to work if and as they are needed, and after that work is done, critical accountability for the show will in large part be deflected onto them.

This refrain about artists made it all the way onto the introductory wall text in the Giardini’s central pavilion. On the other side of the wall from it, Dawn Kaspar has created a live-work studio full of supplies, furniture, and personal belongings. To enact The Sun, The Moon, and The Stars, (2017) she will remain on display in the gallery for the next six months: playing music, making work, chatting with spectators, and foregrounding the notion that artists themselves are the substance of this show. (This appears to be an especially prevalent trend, with Anne Imhof’s German Pavillion winning the Golden Lion.) Say what you will about the constancy of Kaspar’s practice or her disarming sincerity, but as a way to start things off, it felt too literal, and too detached from the tone of the world today.

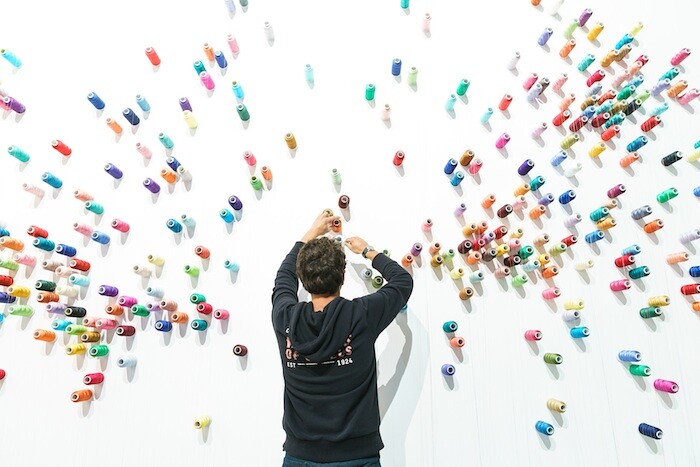

Near the entrance of the Arsenale, Lee Mingwei’s relational aesthetics piece The Mending Project (2009-17) is similarly presided over by the artist or his assistant, pulling thread from a panoply of colored spools down to a table where they fix torn garments for guests and converse. Around the corner, David Medalla’s participatory piece A Stitch in Time (1967-2017)—a great hammock of canvas to which viewers can sew their own colorful additions—also involves live helpers, who greet and explain the project. International survey exhibitions like these have come to operate overtly as marketplaces—with dealers representing artists in the Biennale walking collectors and museum curators through by day and hosting lavish dinners by night—and comparisons between biennials and art fairs are largely treated as old news. What strikes me about the popularity of availing artists to audiences in this way, at the outset of each of the Biennale’s two venues, is how much more than ever it makes this edition of the Biennale feel like a trade show, with veritable booths staffed by artists. The haphazard blurring of performance, relational aesthetics, and explanatory guidance in this way risks creating forums where viewers are bombarded with expanded variations on the elevator pitch instead of rigorous, medium-interrogating art experiences.

Nowhere is the presence of makers more problematic than in Olafur Eliasson’s project Green Light: An Artistic Workshop (2017) immediately following Kaspar’s in the Giardini. The artist has been given a massive room in which to construct a studio showcasing refugees from several parts of the world, toiling to assemble modular green lanterns designed by the artist and sold to benefit NGOs that support immigration. I watched people take cell phone videos of four men displaced from their homes, fussing with sticks at a table as Eliasson stood before them giving what appeared to be a TV interview. This is the deep end of “Viva Arte Viva”’s unconsidered, unintentional exploitations and complete misunderstanding of how contemporary art might be reimagined as something other than an elitist antagonist, out of touch not only with regular people, but, sometimes it seems, lately, virtually everyone and everything.

The Biennale’s nine chapters, ranging from the pavilion of Joys and Fears to the pavilion of Time and Infinity, evoke the nomenclature of Harry Potter with an ontological twist. The notion that this “journey,” as it is described in didactic texts, yields a crafted completeness is at odds with the reality that each chapter piles works into a fanciful narrative category that forecloses an open experience of them.

The most poignant moment in the Biennale is a room of posthumous works by Raymond Hains. The focal point is an impeccably balanced sculpture, Les Jardineries du Sud (1998), consisting of shopping carts loaded with computer monitors, orange and red plastic boxes, and aluminum-mounted images of Italy, plumed with standard-issue garden rakes. It is surrounded by other bodies of work hung on the walls: a distorted, runny American Express logo printed on PVC foam; photographic composites of overlapping old school Macintosh windows containing portraits and abstract forms; and typologically scrambled signage for the national pavilions participating in the 27th Venice Biennale in 1966. The work itself and its position in the show, lofted in quietude over the rest of the Giardini (the stairway leading there is cleared by the sonorous, erratic static of Philippe Parreno’s minimal Quasi-Objects, 2017), suggests reflection on the present, as the future product of the past. Hains speaks in rudimentary dialects of digital technology, international travel, and consumer goods at the inception of the world order they ushered in. As if to say “here we were, before everything went wrong,” the show within a show frames Hains’s 1990s as prescient and innocent, both aware of the domains in which globalization would visually render itself, and naive to how advanced the picture would become today.

Another standout room, of various works from the 1960s and 1990s by John Latham, delves into the central motif of the pavilion of Artists and Books, with stunning assemblages of tomes spread open and bonded to canvas with paint and a vitrine containing a spectrum of symmetrically stained volumes, folded open to blotches of virgin paper. While on one hand the preponderance of other works utilizing bound pages in the Books pavilion muddies a singular practice like Latham’s, it is a more concrete and thus more tangibly poetic framework than, say, the Dionysian pavilion or the pavilion of Shamans. On the other hand, presenting Latham’s work alongside paintings like Liu Ye’s Books on Books (2007–16), riffing on the fathomless contents of rectangular containers like books or canvases, or Al Saadi’s Diaries (2016), a compendium of Abdullah Al Saadi’s thoughts stored in metal boxes in a way he likens to the Dead Sea Scrolls, does plumb the universality of a quotidian object—in this case, books—though it hardly seems the most dire objective to pursue.

As for new works, one highlight is Liliana Porter’s sculpture near the end of the Arsenale, full of carefully arranged errata sweeping a blank white landscape (El hombre con el hacha y otras situaciones breves [Man with an axe and other brief situations], 2017). Frozen in media res, a pin-sized figure in the leftmost position of the display wields an axe. The debris immediately before it, presumably chopped to bits, is dust. Subsequent matter expands in size as a viewer pans their gaze across the tableau: from flakes of stone and Scrabble tiles, to a toy schooner, a broken chair, and a fallen upright piano, all amid a chaos of countless other detritus. It’s hard to say if the figure is a destroyer or a caretaker. Either way, it appears to be returning all the junk to the earth, as another sweeps a streak of blood red sand, and a third stares over an aquamarine tangle of gauze standing in for a boundless ocean. This is an intricately constructed world that captures the precarity, absurdity, and beauty of the array of objects that pollute our own.

Another, in the Giardini, is Rachel Rose’s mesmeric video animation Lake Valley (2017), which tunnels into the existential depths of flatness. Cut paper shapes of reproduced nature illustrations are layered upon each other in sequence to build up an Edenic forest, which is revealed to be a painting that sits in a overwhelmingly tan home made of the same two-dimensional materials. The evolution of plot lies in changes in consciousness; a rabbit-like dog and a girl each sleep, wake, and dream. There are portrayals of caring: the pet looks to the girl, she touches it, feeds it. Maybe prompted by loneliness, the animal is subsumed into the picture, and eventually the seemingly endless flora is revealed to be a modest tract of park confined by the limitless gray outgrowth of cities. As in her other videos, Rose unravels standard depictions of reality as she composes an impressionistic sense of inhabiting multiple, interstitial existences, as we do today as a civilization.

A crescendo of concepts or themes is missing from a voyage through the exhibition, despite the blunt indications of where and how they should occur. Rather, the works that could be considered the show’s anchors hold this context because the artists have built them as microcosms in harmony with the present. This is probably true of all good work in some way. Perhaps in this age of globalized crisis, “Viva Arte Viva” demonstrates that the best way for art to go on living is to give artists a break from being enlisted to peddle ideas that serve grand, amorphous curatorial conceits and to support them in creating their own worlds as they see fit.