In his 2022 book Il rovescio della nazione [The reverse of the nation], Carmine Conelli tells readers about a group of Jesuits who have just returned to the region around Naples in 1561 after years of evangelizing in the Americas. Having honed the skills of spiritual conversion across the Atlantic, they dedicate themselves to doing the same amongst the wild southern “India italiana.”1 Naples was not merely one moment in the terrifying spiral of European history, it was arguably ground zero. As Maria Thereza Alves has shown, the Spanish invasion of Aztec and Inca worlds carted shiploads of crated silver into the ports of Naples,2 kicking off price inflation throughout Europe and initiating an exploratory arms race among the major powers of western Europe to find new worlds to claim and sack. Courts heard testimony about the rights of Europeans to slaughter or enslave others on the basis of their wild nature. Soon the same was said of lands within Europe. Mad contortions of self and other ensued. “Let’s do to us what we did to them,” runs the idea, “because some of us are wild and primitive, and yet none of us will ever be like any of them, because they are Indians uninflected by the potentiality of European Indians.” India italiana can be converted into what they are meant to be, Europeans, and after, their traditions can be celebrated. Non-European Indians can never break the racist and colonialist cellophane they have be wrapped within—from the perspective of Europe. And as Conelli argues, contemporary discourses of internal European colonialism, now heard across the regions of Italy, bely its Janus face.

Tracing a similar circular reasoning is what led me to Trento, Italy and then down to Naples to study the powerful exhibition “Jimmie Durham: Humanity is not a completed project.” This is Durham’s first major retrospective since his death in 2021, and the last show of Kathryn Weir as artistic director of Madre. The show consists of one hundred and fifty pieces, including poems, sculptures, videos, carvings, and artistic research material, that stretch from his earliest and some unseen pieces to his last, specifically pieces focused on the potentials and limits of particle physics for a new ecological imagination. The curatorial aim, however, is not everything he did must be seen. It focuses on Durham’s deconstruction of identity claims, rather than on the controversy surrounding his own, disputed claims to be Native American.3 Instead, we are led across rooms in such a way that, when we are done, Durham’s reading of the European Indian—filled equally with rage, satire, and cool insight—has been fully summoned. This is why I wished to see the show. To understand how this summoning resonates in the Italian mezzogiorno. Who is Durham there, and how does his artistic practice appear? And what is this new discourse of internal European colonialism from the perspective of Durham’s work?

“Humanity is not a completed project” argues that Durham’s work should be understood as a critique of Europe’s obsession with “the Indian” rather than with what Durham claimed to be or was. The show announces this intention by beginning with the sculpture Gilgamesh (1993), a metal ax jammed into an enormous wooden door, suggesting the inexorable link between technological progress and global ecocide and genocide and the western obsession with the violence of cutting, marking origins, insisting on difference, rather than teasing out the irreducibility of historical relationality and entanglement. Gilgamesh sits next to Une blessure par balles from the body of works “Labyrinth” (2007), another tree trunk, this one sliced longitudinally to reveal the histories of human and more-than-human entanglement: insect paths inward are shown to have been made possible by bullets lodged in the trunk during World War II.

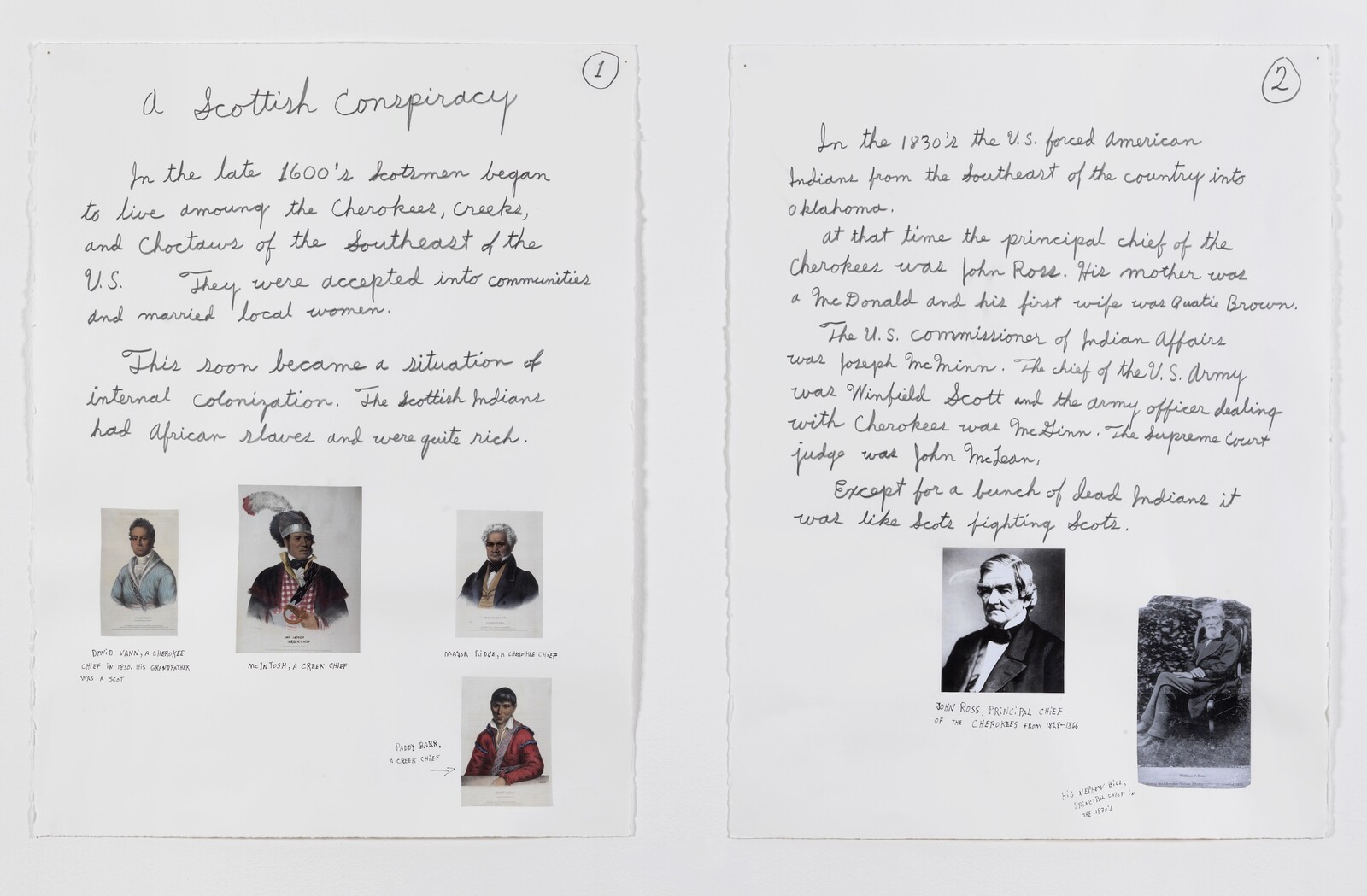

The works suggest that Europe does not wish to look at these complex entanglements of human and more-than-human existence. It wants clean cuts, clear lines between races, and uncomplicated lines of descent that can be verified by state authorities. By room four, the show uses A Scottish Conspiracy (2010) to indirectly comment on Durham’s own controversial lineage by changing the focus—that is, to the European who wants a registered, lodged, stamped authenticated Indian. The work uses historical portraits organized as if in a family tree: Cherokee chiefs descended from Scottish settlers from the 1600s and Cherokee women, laying bare the politics of race and gender in what J. Kēhaulani Kauanui describes as the colonialism of blood quantum.4 It is also a way of aligning the show to Durham’s position relative to those who critiqued his identity claims, namely, that it’s less important to consider what he is or is not than to understand how as a poet, thinker, and artist, since his first formal training in Geneva (1969–73), he has focused on demonstrating the violence of discourses of origin so essential to the European Indian, and the ways they sweep gender, sexuality and race into preserving a hierarchy of white power. Europeans can celebrate their own “premodern” traditions. But while Europeans can suffer the effects of folk tourism (Durham explored this in his graduation work God’s own drunks (1974), shown in Naples for the first time, and later in Maquette for a Museum of Switzerland, 2012), the ramifications of this form of museumification are never equivalent in their social, political, and ecological effects, any more than the salvation of European “primitives” put them in a space of equivalence with the external worlds Europeans ravaged.

This is why I traveled from Trento to Naples—and why I will be returning nearby to my ancestral village, Carisolo, at the beginning of May this year with seven other members of Karrabing Film Collective. We are in the middle of a project we call Rising Seas | Melting Glaciers. It pivots between two ecological disruptions, namely melting glaciers and rising tides, and two political historical forms and fates of colonial dispossession, namely the destruction of village/family-based commons in Trentino in 1805 and the invasion of Karrabing lands in the coastal land of the Northern Territory, Australia, in 1869. We are not interested in a comparative project. We are not seeking to demonstrate how my ancestral clans in Carisolo and my Indigenous colleagues’ geographical relations at Mabaluk/Bamayak were the same or different before the forces of settler colonialism slammed into them. We want to demonstrate the conditions of a spiraling European violence. As Glen Coulthard has noted, Europeans such as my Carisolean ancestors were dispossessed into proletarianism, or what Aileen Moreton-Robinson calls the logics of the white possessive.5 Not so with my Indigenous Karrabing colleagues.

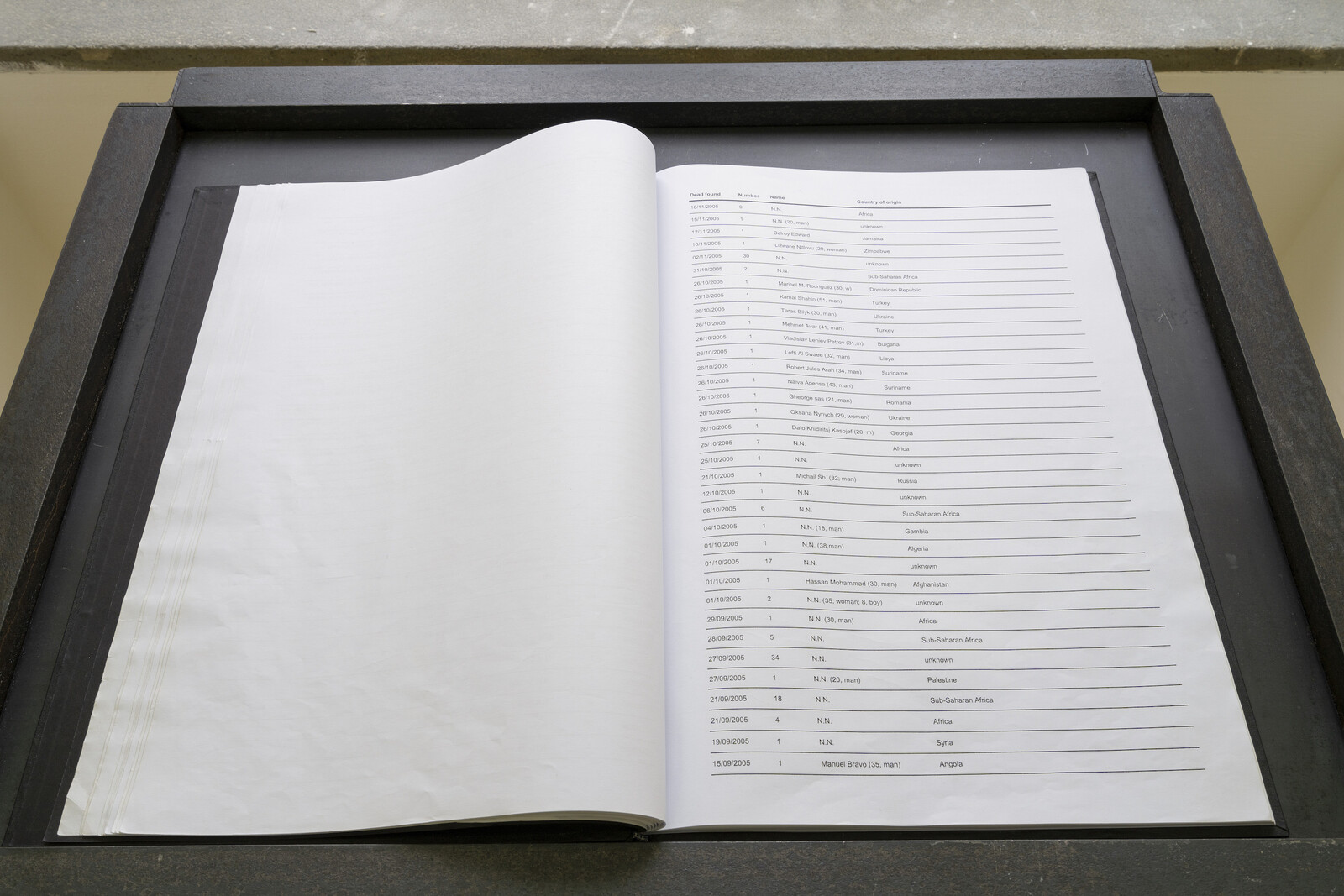

The curatorial approach in “Humanity is not a completed project” is to show Durham’s work as primarily focused on the architectural spirals of violence that are washing onto European shores as they can no longer contain their own excrement in “off-shore” colonized lands. Perhaps the most unnerving are Malinche (1988–92) and Cortez (1991–92) in the context of A Street-Level Treatise on Money and Work (2005), which alludes to John Maynard Keynes’s A Treatise on Money (1930). Malinche evokes the story of Malintzin (ca. 1500–29), a Nahua woman who was cast as a traitor to her people for having served as an interpreter and lover of the Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés. Durham used Malintzin’s head for his earlier sculpture Pocahontas and the Little Carpenter (1988), creating a powerful sense of the repetitive compulsion by which settlers used gender and sexuality not merely to advance colonization but to divide Indigenous communities. Inexorably tethered, but never allowed in the same room, Malinche and Cortez are the two sides of European colonialism. They represent the “Museum of European Normality”—the title of a 2008 Durham work—which attempts to swallow everything into the architecture of a European progress. Even the idea of colonization now serves to bolster Europe against those it ransacked. If the new mezzogiorno discourse of a north Italian colonization reveals and obfuscates the actual spiraling effects of European invasions, so does the mobilization of the imago of a Prairie Native American man in ceremonial headdress by the political party Lega Nord [The Northern League] bolster its anti-southern and antiblack immigration rhetoric. Lega Nord did not say, what we did to them is coming home to roost. It claims the north too was and is being colonized. And “Humanity is not a completed project” does not say whether Durham was or wasn’t assuming an identity that was not his to assume. Instead, it presents works such as Evidence (2016), an installation Durham produced for the small German town of Goslar after having been awarded the Goslar Prize, focused on a fictional woman accused of being a witch. And we are presented with Anti-guest book (2008), a list of the names of five thousand refugees who lost their lives crossing the Mediterranean Sea from 1993-2008.

This is the heart of Weir’s innovative reading of Durham’s work, and its legacy: that it might help us understand what I have been calling the European counterreformation. No longer able to anchor themselves in the presupposed superiority of European Christianity and capitalism, white nativists in Europe and the colonial diaspora search for new moorings in their own premodern heritage. But this search often obscures the social and ecological fractures European invasions wrought. Europe can try to find its own internal Indian, but it cannot erase the uneven sedimentations of care and abuse. The results are the men, women, and children arriving from elsewhere onto their shores.

“Jimmie Durham: humanity is not a completed project” is at Madre Museum, Naples through May 8, 2023.

Carmine Conelli, Il rovescio della nazione. La costruzione coloniale dell’idea di Mezzogiorno (Napoli: Tamu Edizioni, 2022).

See Maria Thereza Alves, Thieves and Murderers in Naples: A Brief History on Families, Colonization, Immense Wealth, Land Theft, Art and the Valle de Xico Community Museum in Mexico (Spoltore: Di Paolo Edizioni/ No Man’s Land Foundation, 2020).

See for example Aruna D’Souza, “Mourning Jimmie Durham,” Momus (July 2017), https://momus.ca/mourning-jimmie-durham/.

J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2008).

Glen Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty (University of Minnesota Press, 2015).