Guy Mees (1935–2003) was a leading figure of the Belgian avant-garde whose enigmatic work combined formal diversity with conceptual rigor. A consecutive pair of exhibitions at Barcelona’s ProjecteSD—the first from March to April, the second from May to June—shed light on his career, offering carefully curated series of works alongside archival materials that situate his practice in a wider art-historical background. Mees’s interest in serial structures, repetition, formal reduction, and industrial materials was in some ways typical of minimalism. But as these two exhibitions attest, his highly personal artistic language balanced formal rigor with fragile materials—stretched lace, pale neon, narrow strips of paper—to lend his work its characteristic delicacy.

Each exhibition loosely corresponds to a distinct period in Mees’s career, during which he produced a series of works under the collective title “Verloren Ruimte” [Lost Space]. The first group, made between 1960 and 1967, feature simple, geometric wood and aluminum sculptures overlaid with industrial lace. The second, which Mees began in the mid-1980s and completed in the mid-1990s, is looser and more vivid, comprising strips of colored paper pinned to the wall. Despite their formal differences, both series investigate the relationship between art objects and their exhibitionary environments. Displaying these works in consecutive exhibitions feels apt, offering viewers a sense of Mees’s progression as an artist while allowing the differences and similarities between each series to emerge.

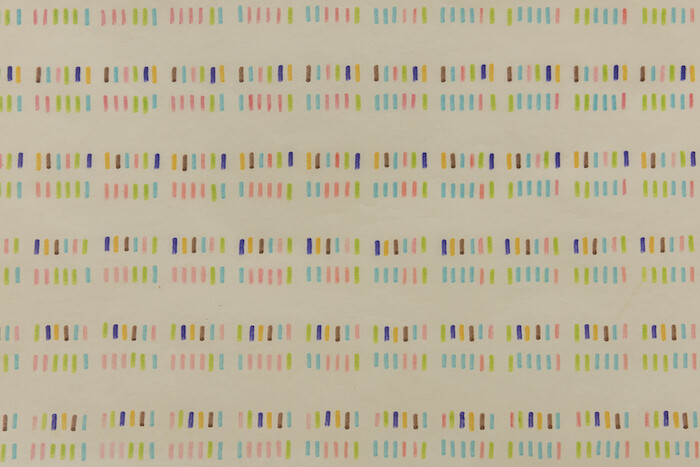

Mees worked across a range of media, including actions, films, and photographic series. During the first installment of the exhibition, three black-and-white photographs taken from “Level Differences” (1970), a larger series of works, were presented near the entrance to the gallery. Each image features three men standing stiffly upright on a podium assembled from concrete blocks, their positions changing in each photo. By playing with these permutations, Mees’s photographs at once evoke and subvert notions of power and social hierarchy. In later works, Mees assigned a color to each position occupied by the three people to produce a series of mesmerizing chromatic charts. In Untitled (1970), for example, vertical lines in turquoise, blue, yellow, green, brown, and pink marker pen form rhythmical, iterative patterns using strictly limited resources.

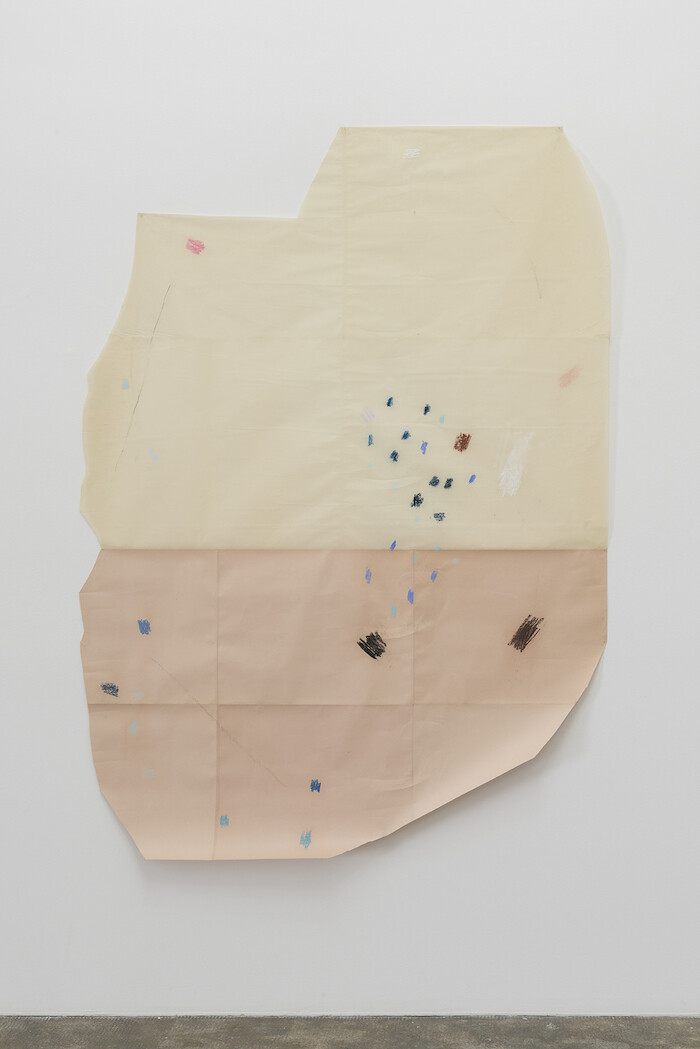

The artist’s interest in serial structures is absent in the works on paper from the 1970s displayed in the main gallery. They are mounted to the wall with pins, a minimal display strategy that enhances their fragility. Made from colored, glued-together pieces of paper (so that the differences in their textural and chromatic qualities is visible), these are light, subtle works that invite contemplation. Inscribed on their surfaces are unevenly distributed spots of color, strokes of pencil, and handwritten phrases. “The weather is calm, cool, and soft,” reads a line written on Untitled (1978). In Blauw met Eucalyptus [Blue and Eucalyptus] (1970–75), “blue and eucalyptus” appears against a yellow background. Such phrases remind viewers that the experience of the world is often mediated by language. Mees never spoke or wrote about his work, but a text written by Wim Joris Lagrilière under Mees’s instruction, a copy of which is displayed in the entrance to the gallery, offers one conceptual frame for the exhibition’s title:

“The Lost Space is an adjoining space. The Lost Space is complementary to present-day living space. The Lost Space does not have a clear-cut function. The Lost Space is space as utility object in which bombast becomes more difficult and tangibility easier. The Lost Space is simply the body specified according to form, color, taste, smell, sound.”1

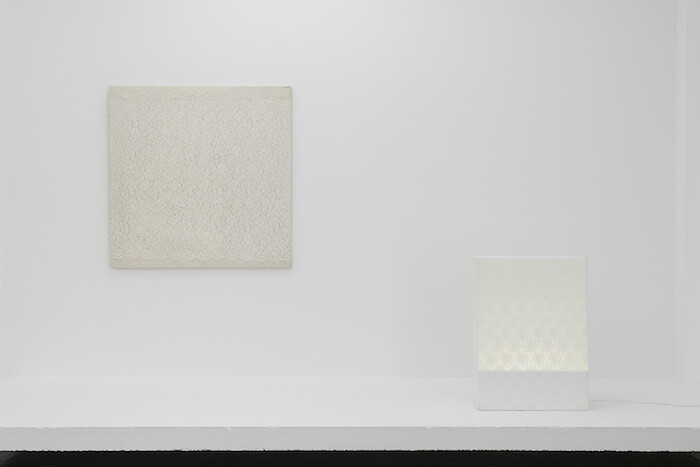

Two titular works from Mees’s first “Lost Space” series close this first exhibition. The first (1960–64) is a square aluminum panel covered with intricate, industrially made lace; the second (1965) is an upright, rectangular box, built from a wooden frame covered with taut lace, with a neon light glowing inside it. These striking pieces evoke the severity and restraint of minimalism while also subverting it. Like the large monochrome works on paper, these sculptures invite sensory perception of the nuanced textures of their surfaces (the “present-day… tangibility,” perhaps) while drawing attention to their spatial arrangements.

In the second chapter of the show, the gallery’s entrance contains archival material and artworks that evidence Mees’s conceptual development and growing interest in the expressive potential of color. During the mid-1980s, he embarked on a series of attempts to extend the language of painting beyond the bounds of the canvas and to transpose painterly techniques into three-dimensional spaces to create sensory environments. This can be observed in two documentary photographs and an exhibition poster from Mees’s 1993 solo show at the former Paleis voor Schone Kunsten (now BOZAR) in Brussels. There, he painted the baseboards of the exhibition space in different colors while leaving the remaining areas predominantly empty. This modest intervention subtly configured a pictorial space while also drawing attention to a residual area—the “Lost Space”—of the white wall.

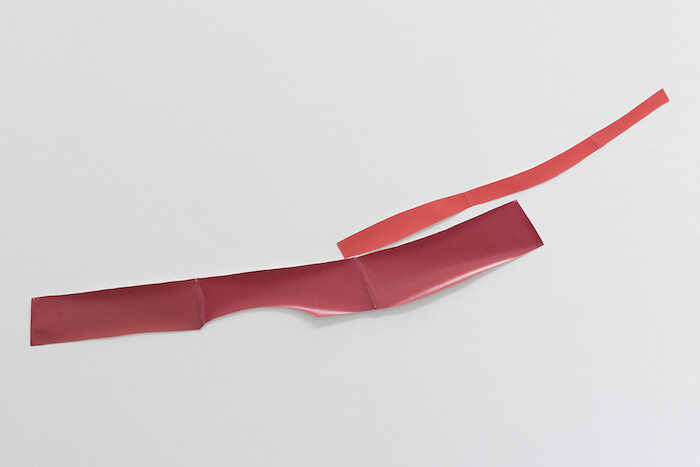

The main room includes works from the second “Lost Space” series. In distinction to the pale shades and repetitive forms of the earlier pieces, these are brightly colored and more gestural, comprising thin, cut-out strips of paper pinned to the wall. There’s a vivid green piece that curves horizontally, a narrow red-and-orange strip resembling a flame, and a row of shiny strips of aluminum foil. The result is a symphony of rhythm and harmony achieved with minimal resources. Elongated and irregularly colored, the forms appear to hang suspended around the space and fill the room with dynamism. Mees’s poetic practice pursued lightness, subtlety, ephemerality, and the everyday, but his reduction of media and simplification of visual languages were radical and daring—always seeking the limit between being nothing and being everything.

Quoted in Dirk Snauwaert, “In Spite of Painting Reconstructions of Pictorial Space,” Guy Mees (Ghent: Ludion/Cera, 2002).