The “Forum Expanded” section of the Berlinale, an assemblage of exhibitions distributed across three venues and any number of screens, charts the points at which cinema meets the visual arts. This year’s edition, titled “An Atypical Orbit,” aimed to set in motion “fluctuating proximities—political and personal legacies which often lie in shambles” and to “challenge the status quo through exhibiting works that redefine cinema.”1 In attempting to solve two problems—to host a platform for political articulation, and to critically engage with moving images and media as such—the Forum Expanded faced a conundrum: its archival and historiographic approach, as well as the aesthetic and political emphases in the overall selection of works and conversations, induced a certain lethargy: a sense of being unwilling or unable to respond to those current emergencies which do not yet have established narratives.

In Betonhalle’s entrance corridor, Tenzin Phuntsog’s Dreams (2022) set up the exhibition’s dream-like ambience. The work portrays a sleeping couple— immigrants from Tibet to the US—floating in space against a quiet, blueish monochrome background. The pair reappear in a two-channel video, Pala Amala (2022), posing silently in nondescript settings. These large-screen, meditative works sat in contrast to the small, phone-like screens which presented short fragments of domestic videos sent from Tibet. The effect was to emphasize disjuncture and distance, filling the space with memory and longing. Tamer El Said’s Borrowing A Family Album (2023)—an installation of still and moving images, fragmented, reshuffled, animated and circulated through multiple distributed screens—also conveyed an ambiguous sense of loss and haunting memories, employing found amateur footage shot in 1960s Athens. These blurred glimpses from the past provoke an eerie sense of familiarity: the subtle beauty of this work was in its proposition that reliving one’s past through someone else’s story is possible.

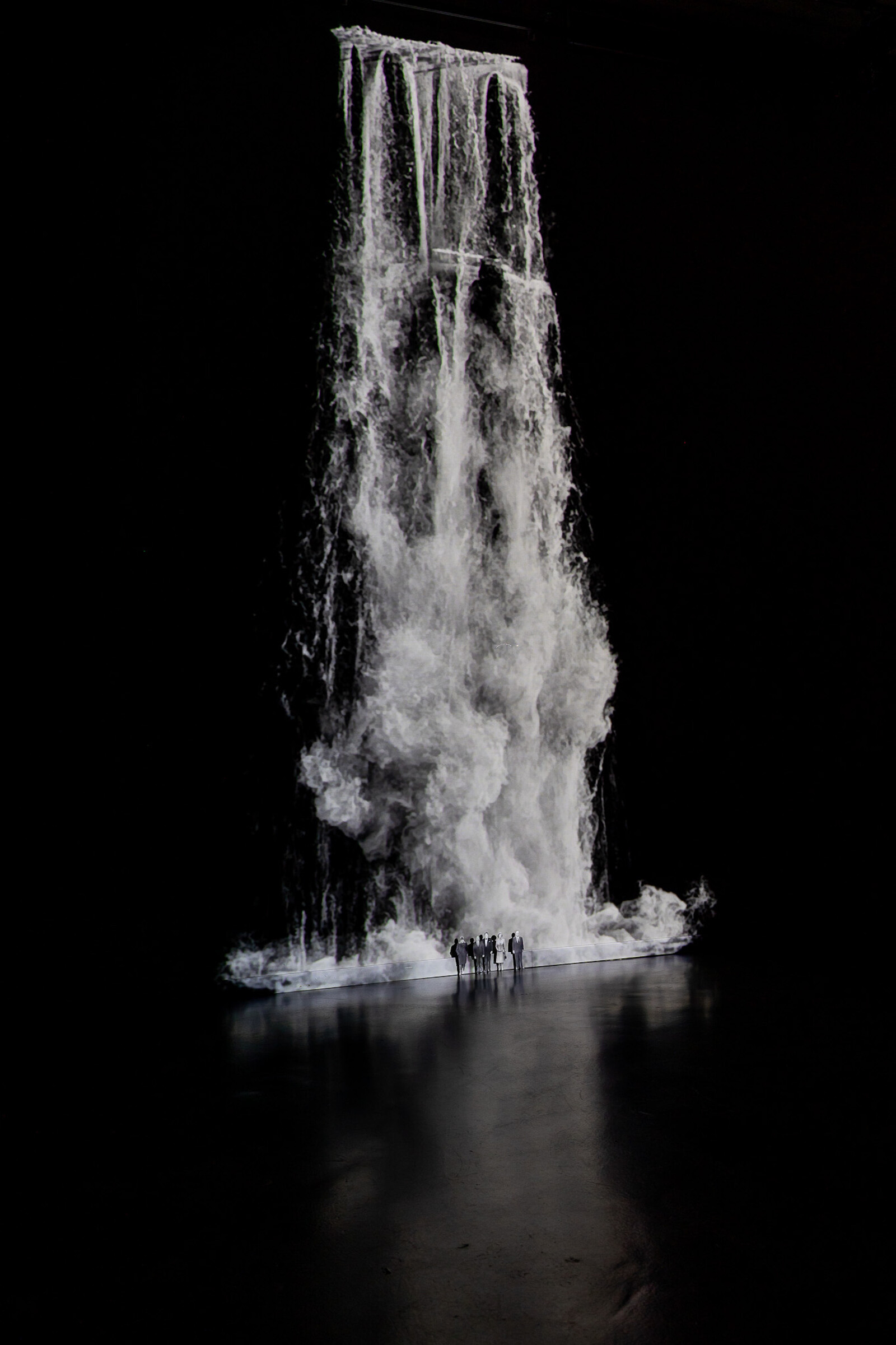

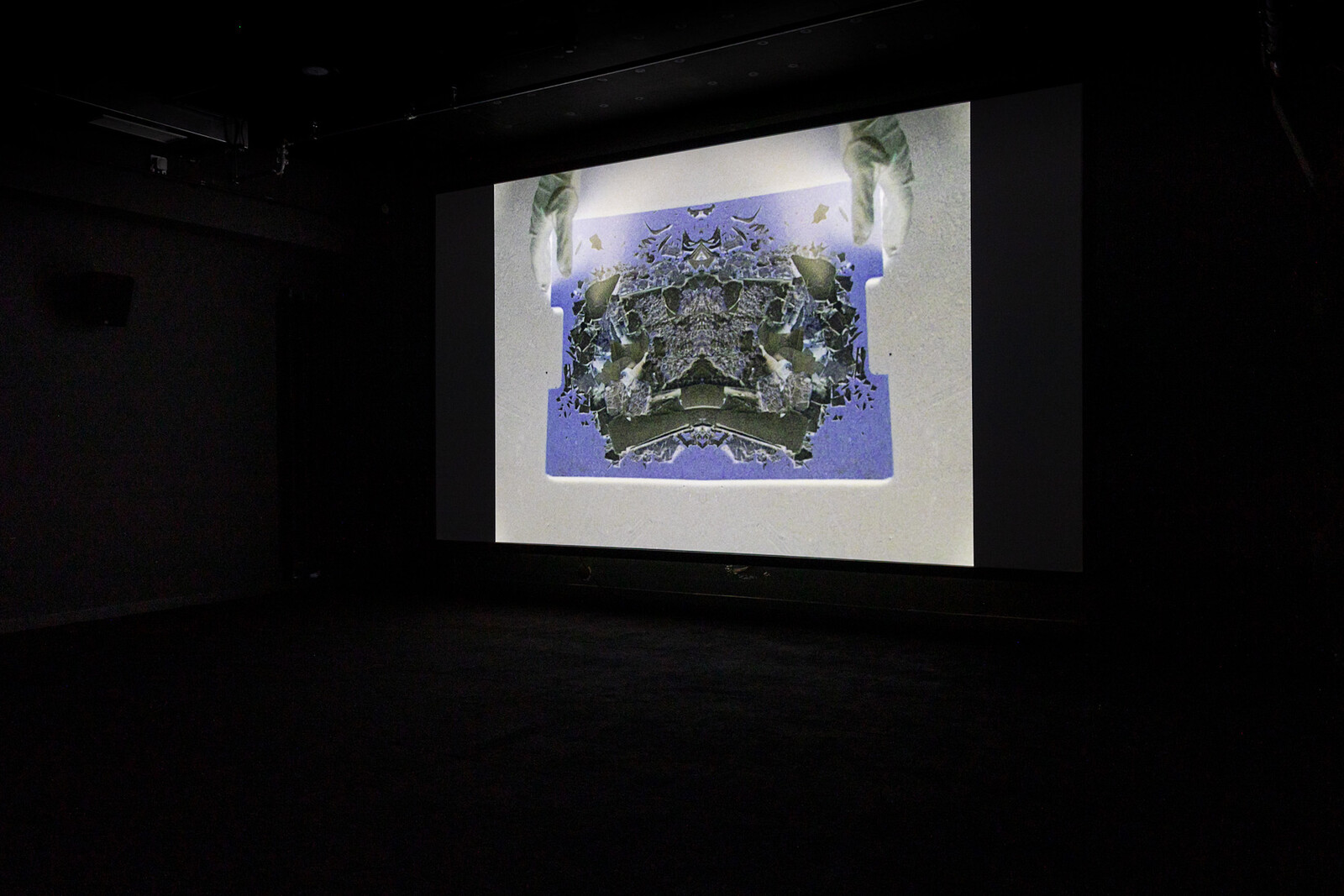

In a section dedicated to “expanded cinema,” several works experimented with fresh ways of presenting and receiving moving images, beyond the classic combination of projector, screen, and dark room. Among these formats were Walid Raad’s waterfall projection Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you (2022), which brought a touch of irony and strange relativism, or Un Gif Larguísimo [A Very Long Gif] (2022) by Eduardo Williams—a gigantic video of a swallowed-pill camera that travels through the digestive system, accompanied by smaller videos where a telephoto lens is glazing over a distant urban landscape—which combined the ultimate embodiment of the gaze with an effective disembodiment. The show also paid tribute to Arsenal’s history—and that of experimental film—by showing series of works by the recently deceased Takahiko Iimura and Michael Snow, both of which pay particular attention to the materiality of moving images and the screens. The screens and projections were presented like floating islands, with their subjects often long dead or stored safely in the archive, or, even if slightly politicized, reduced to memory-dreams. Old CRT-TV sets served as a reminder of how new technology has offered the opportunity to broadcast and relate to the most pressing events. But here, liminal spaces, like dreams, video tapes, and archives only mimicked a sense of urgency that was, in fact, kept at a safe distance.

Other works demonstrated the ways in which film can be imagined as a political and activist tool. The Marshall McLuhan Salon presented Tartupaluk (Prototype) (2023) by Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, a multi-channel VR installation that invited viewers to enter an imaginary Republic of Tartupaluk—a political utopia situated in a specific geography. As Laakkuluk explained during her joyous artist talk, Tartupaluk is a tiny island in the territorial waters claimed by both “what is now called Canada” and “what is now called Greenland,” an Inuit homeland that has been “used and abused by colonial states” for the past four hundred years. Critiquing the “men’s war” between Canada and Denmark, Laakkuluk proclaimed herself president of the republic—“a delightful place, where a nation of lovers look after each other, and find themselves beautiful, and get a stamp in their passport every time they’ve had sex.” Through queering, mask dance, and carnivalesque theater, the act of claiming Tartupaluk suggests humor as a subversive political strategy and a means of overturning oppressive social systems.

Laakkuluk’s work addresses profoundly complex and devastating topics related to colonialism, subsequent displacement, imperial erasure, slow violence, and trauma. Yet her work proposes the imagination of joy and freedom supported by a history of powerful indigenous matriarchy. At SAVVY Contemporary, the sub-exhibition “Our Daughters Shall Inherit The Wealth of Our Stories” presented the films of Yugantar Film Collective, introduced as the first feminist film collective in India, founded in 1980 during the country’s postcolonial socio-political rearrangements, human rights, and environmental movements. Four films, produced by the collective—and subsequently lost or damaged, requiring more than a decade of restoration work—chart early emancipatory efforts to organize labor unions and to advocate for women in both family and society. The films document the struggle of their own creation: entering and inhabiting spaces, allowing ideas to form and emerge. The scenes show women at their most vulnerable, claiming subjectivity while still facing multiple forms of structural violence and systemic injustices. Here, that intimacy manifests as empowerment; we’re invited to come in and witness those vulnerabilities, as well as agency, resistance, and solidarity.

The films were accompanied by archival materials, prints, and manifestos, to create a site for discussion: the curators animated these materials through a baithak, a carpeted sitting area for daily meal sharing, talks, and debates. The project was in tune with SAVVY’s mission, stated on their website, to foreground feminist, decentralized, and engaging forms of knowledge production. Navigating through the films, exhibitions, and talks gave a strong sense of what filmmaker and scholar Trinh T. Minh-Ha has described as an attitude of “talking nearby instead of talking about”— co-producing the truth with those willing to participate rather than simply presenting it. At the same time, something very important was missing from SAVVY and in the rest of the Forum, including its film program, where questions of colonialism, imperialism, and decolonial optics served to reiterate the binary of the West and the Rest instead of scrutinizing it. This iteration of Forum takes place against the backdrop of the biggest war in Europe since World War II, yet here—the only discursive platform of Berlinale—was the only place where this war was not addressed through the program. All while unfolding events on the eastern fronts present enormous material for theorizing alternative forms of organizing and collectivity, as well as new forms of imaging, media, and expanded cinema.

It might be supposed that this critique enters the text because its author is herself a subject of the current war (although my eyes are crafted with blood and other resources).2 But the problem here is much bigger: continuous occidocentrism and attempts to rebalance the Global South re-enhance discursive distortions that need to be questioned, as they feed into a massive genocidal and ecocidal war that has a vast geography and a very long history, and will not stop. A marginal but important critique has emerged, addressing decolonial scholars from Global South for their views on the Russian invasion, which dangerously reiterate Kremlin propaganda. Fixating on the west as the root of all evil, as Adrian Ivakhiv points out, produces a strange amnesia.3 Centuries of Russian imperialism, rendering lands into deserts and killing millions, were ignored when the Soviet doctrine felt right for those who were far away from its realities. Moreover, a false mythology of the Russian/Soviet imperial liberating mission presumably helping people in India, Africa, and the Americas continuously contributes to the selective blindness and inability of leftist thinkers, North and South, to show solidarity with Ukraine, and to actually make a human and discursive contribution. Eastern Europe is repeatedly not part of Forum Expanded. While doing justice on the micro-scale, the exhibition presented a rather typical orbit. Even with the plurality of presented works and contexts, it builds upon what is already an established narrative, without entering the space that is bleeding, that is too close, too unsafe.

Betonhalle of silent green, SAVVY Contemporary and, the Marshall McLuhan Salon of the Embassy of Canada in Berlin were the spaces filled by curators Ala Younis, Uli Ziemons, Karina Griffith, Shai Heredia, Chiara Figone, and Abhishek Nilamber. For citations, see 73rd Berlin International Film Festival, “Forum Expanded” press release www.berlinale.de/en/2023/news-press-releases/227542.html and catalog.

Asia Bazdyrieva, “No Milk, No Love,” e-flux journal #127 (May 2022), www.e-flux.com/journal/127/465214/no-milk-no-love/.

Adrian Ivakhiv, “Decolonialism divided against itself…”, The University of Vermont blogs (March 2023) bit.ly/3TODoTB.