May 5–September 30, 2018

Cornwall’s picturesque fishing villages, tearooms, and sandy beaches attract 15 million visitors a year, and its southern coastline is dubbed—only half-jokingly—the Cornish Riviera. Part of its attraction derives from art: in the 1930s, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron, Naum Gabo, and other leading modernists established a colony in St Ives, transforming the coastal town into an internationally recognized hub of the avant-garde. If tourism now contributes around £2.6 billion to the area annually, it also breeds discontent (“emmets”—“the ants”—is an old Cornish nickname for non-locals). The decline of mining and finishing industries throughout the twentieth century have left Cornwall the second poorest region in Northern Europe, with some of the worst deprived neighborhoods in England. But recent years have also seen an influx of arts funding to the region, from both local and national governments. Tate St Ives reopened in late 2017 after a £20 million redevelopment, while smaller venues such as Kestle Barton, a gallery and farmstead on the Lizard peninsula, have improved their spaces and launched more ambitious exhibitions. Against a backdrop of contentious debates about the role of art in Britain’s deprived communities in an era of austerity, Groundwork—a five-months-long season of art in multiple venues across Cornwall—aims to nurture connections between artists, venues, and local communities that will develop throughout the program, and potentially outlive it.

Curated by Teresa Gleadowe, Groundwork features 15 international artists, including Francis Alÿs, Tacita Dean, and Steve McQueen, working across a range of media. Alongside films, installations, sound works, and performances are a series of artist-led field trips—such as Ben Rivers’s and poet Paul Farley’s investigation of Helston’s edgelands, artist and quarryman David Paton’s tour of granite quarries in Cornwall and Dartmoor, and painter Naomi Frears’s forthcoming collaboration with electronic musician Luke Vibert—and an education program involving local schools, colleges, and universities. As its name suggests, the project aims to lay artistic groundwork in Cornwall, building on an existing network of established art venues—Tate St Ives and Kestle Barton, as well as Newlyn Art Gallery and the Exchange, and the Cornubian Arts & Science Trust (CAST)—alongside other sites, such as Richmond Chapel in Penzance or the snooker club in Porthleven. The range of venues, artistic approaches, and themes is crucial for Groundwork’s integration of art within local communities—not only showing work in a broad range of spaces, but commissioning new pieces which directly engage with local sites and histories.

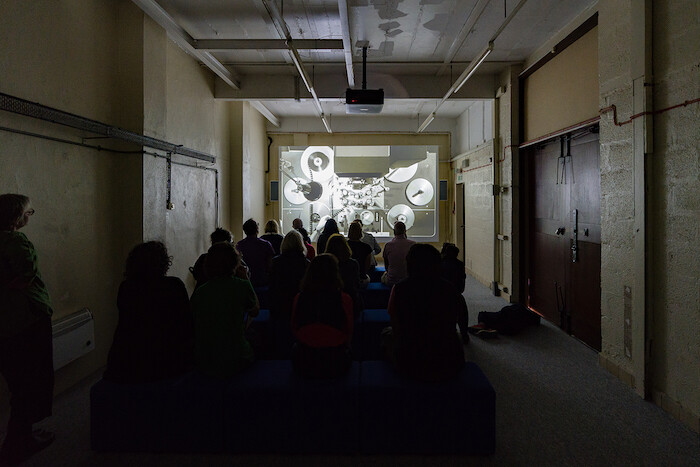

At CAST—a restored school building in Helston which became a key Groundwork venue and its base of operations—Steve McQueen’s 35mm film Gravesend (2007) is projected in a darkened assembly hall. It is a lyrical piece of reportage on the mining of coltan, a mineral essential to the production of cellphones and laptops. The film opens in a high-tech laboratory somewhere in the West, where robots process the dull black metallic ore, before cutting to the Congo, where men in mine shafts dig with spades and bare hands, searching for the metal. It portrays the exploitative (but often hidden) processes by which value is extracted from the land but accrued elsewhere—a theme which resonates with Cornwall’s history of mining and quarrying, while drawing the viewer’s attention to the ongoing, neo-imperialist ravaging of Central Africa’s resources. A soundtrack of murmuring voices, like a thousand cellphone conversations chattering at once, suggests the interconnectedness of such apparently distant events.

At the nearby Helston Museum, two films by Sean Lynch are tucked in between the existing displays of local material culture. Playing on a television among butter churns decorated with bluebells is Latoon (2006–2015), a short film built around an interview with the folklorist Eddie Lenihan. In 1999, Lenihan warned an Irish council about a whitethorn bush that was going to be destroyed by a new highway, claiming it was an important meeting point for warring fairies, and that its destruction would curse the new road. His story was picked up in the Clare Champion and the New York Times, and the motorway was redirected. Lynch’s interest in myths and monuments is developed further in What is an Apparatus? (2016–18). Installed among a display of Victorian school desks, the film’s sarcastic, unreliable narrator poses conspiracy theories and anecdotal histories over images of supermarkets or parking lots shot in Helston. In one scene, the narrator describes a row of boulders on the town’s outskirts as “car salesmen turned to stone.” The decision to screen the films in the local history museum feels apt: both of them tease out the relationship between folklore and nationalism. Lynch’s playful scripts gently encourage viewers to take a skeptical view of the displays surrounding his films, which in turn offer tactile substantiations of Lynch’s ludic videos. This critical reciprocity feels indicative of Groundwork’s broader curatorial ethos. Rather than reinforce Cornwall’s sentimental histories, or parachute international artists into incongruous environments, it seeks to find points of connection.

The most unusual site in Groundwork is Goonhilly Earth Station, hidden down the country lanes south of Helston. Built in 1962, the satellite station was used in the first transatlantic television broadcasts. There’s a Thunderbirds feel to the enormous dishes, only some of which are still functional. The former BT offices are overgrown with bushes while the site has become a Segway activity ground complete with a cone-lined obstacle course draped with camouflage nets. Two films are looping in an old battery store. Simon Starling’s Black Drop (2012) is about the transit of Venus across the sun, an astrological phenomenon that takes place every 243 years and offers a crucial measurement of the Solar System. As the World Turns (2018) by Semiconductor—the art duo Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt—is a short film shot at Goonhilly that captures the dishes at sunset and intersperses the hand-held footage with raw satellite data collected by radio astronomers. The films pale against the rich atmosphere of the earth station, which has the feel of a lost theme park. “Welcome to Goonilly, future world,” reads a greening sign.

The real impact of Groundwork is yet to be seen. Is this just sugar for the ants? Or will the spaces continue to grow beyond the duration of the season to become beneficial, not just for acclaimed artists and international visitors, but also for the local population? Given the season’s ambitions to foster long-lasting connections in a historically deprived region, such questions are still difficult to comprehensively answer. Manon de Boer’s newly commissioned film, however, is an example of the best kind of artistic engagement, as it offers a glimpse of how this season might contribute to a wider conversation about the role of art in the region. For the film Bella, Maia and Nick (2018), screening at Kestle Barton, de Boer worked with three music students from the Helston Community College, filming them as they improvised on saxophone, flute, and clarinet in a little room by the sea in St Ives. The film is the inaugural part of a larger planned project—titled From nothing to something to something else—in which the artist will record children as they make music, cultivating something more local, and experimenting with the expressive potential of improvisation. For so many centuries, Cornwall’s economy has been built on processes of extraction—mining, quarrying, and so on—but de Boer’s work puts forward a different flow of value: a movement from nothing to something. This is precisely what Groundwork contends: that given the right conditions art might incrementally build connections and lay the foundations for a new kind of heritage, a “something else” somewhere down the line.