In February 1959, Walter Menzl walked into Munich’s Alte Pinakothek and splashed acid over Peter Paul Rubens’s The Fall of the Damned (ca. 1620), a baroque vision of biblical end times replete with corpulent humans being consumed by horned demons and fanged animals. Contemporary news photographs show museum staff conveying the three-meter-tall painting, its center visibly stained, like a stricken soldier. That stain, the residue of an action intended by Menzl to jolt the television-gawping masses and draw attention to his own unpublished writings, is central to understanding Johannes Phokela’s work, pictorially as much as conceptually.1

In 1993, six years after relocating from Johannesburg to London, Phokela presented his master’s degree show at the Royal College of Art. His budding interest in iconoclasm was summarized in Original Sin - Fall of the Damned as Damaged, 1959 (1993), a compact, murky reproduction of the vandalized Rubens painting. The work features two embellishments: a red dot and pink oval at the topmost point of the stain. Such geometric appendices would become a hallmark of his classically influenced and technically accomplished figure paintings. Also part of Phokela’s degree work was a larger canvas, Fall of the Damned (Yellow) (1993), which resembles Guy Head’s muddy copy after Rubens, dated before 1799 and held in the Royal Academy Collection in London, and features uncharacteristically perfunctory figures rendered in brown paint on a yellow ground.

Both these student pieces by Phokela appear in “Only Sun in The Sky Knows How I Feel (A Lucid Dream)” at Zeitz MOCAA, a timely and concise survey of this underrated South African painter’s work, curated by Koyo Kouoh and Storm Janse van Rensburg. The title, chosen by Phokela, is lifted from Nina Simone’s 1965 song “Feeling Good.” In a recent interview the artist described feeling upbeat about the exhibition, delays and compromises related to loans notwithstanding. It forms part of the museum’s planned but pandemic-delayed series of in-depth, research-based solo exhibitions focusing on important artists from Africa; a show on Tracey Rose is forthcoming.

Phokela’s ongoing détournement of key works by Rubens, Édouard Manet, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder can seem of a piece, especially given the remediation of the western canon by contemporaneous painters such as Kehinde Wiley and Michael Armitage, who variously quote Diego Velázquez and Paul Gauguin. But such a generalization ignores the specific temporalities and lineages informing Phokela’s practice. The artist, who lives in Johannesburg but speaks with a noticeable London twang following two decades spent in England, hijacks and reroutes art history in a way comparable to his particular contemporaries, Lubaina Himid and Yinka Shonibare, both of whom reworked William Hogarth in works from the 1980s and ’90s.2

The curators do not purposefully explore Phokela’s dual inheritance as a Soweto youth mentored by pleinairist turned paper experimenter Durant Sihlali, and as a young painter shaped by the aftershocks of the British Black arts movement of the 1980s. Their thematically grouped hang (“consumption and social commentary,” “religion and violence,” and “history”) nonetheless features two works that acknowledge his South African and English apprenticeships. Displayed early on, in a section stocked with superbly executed scenes of white avarice and Black burden, the petite etching Knitting Woman and Child (1987) is a domestic idyll from a time of social insurrection. Together with Original Sin - Fall of the Damned as Damaged, installed in a room exploring Phokela’s reinventions of well-known paintings, the two works declare his elemental faith in the figure as narrative device.

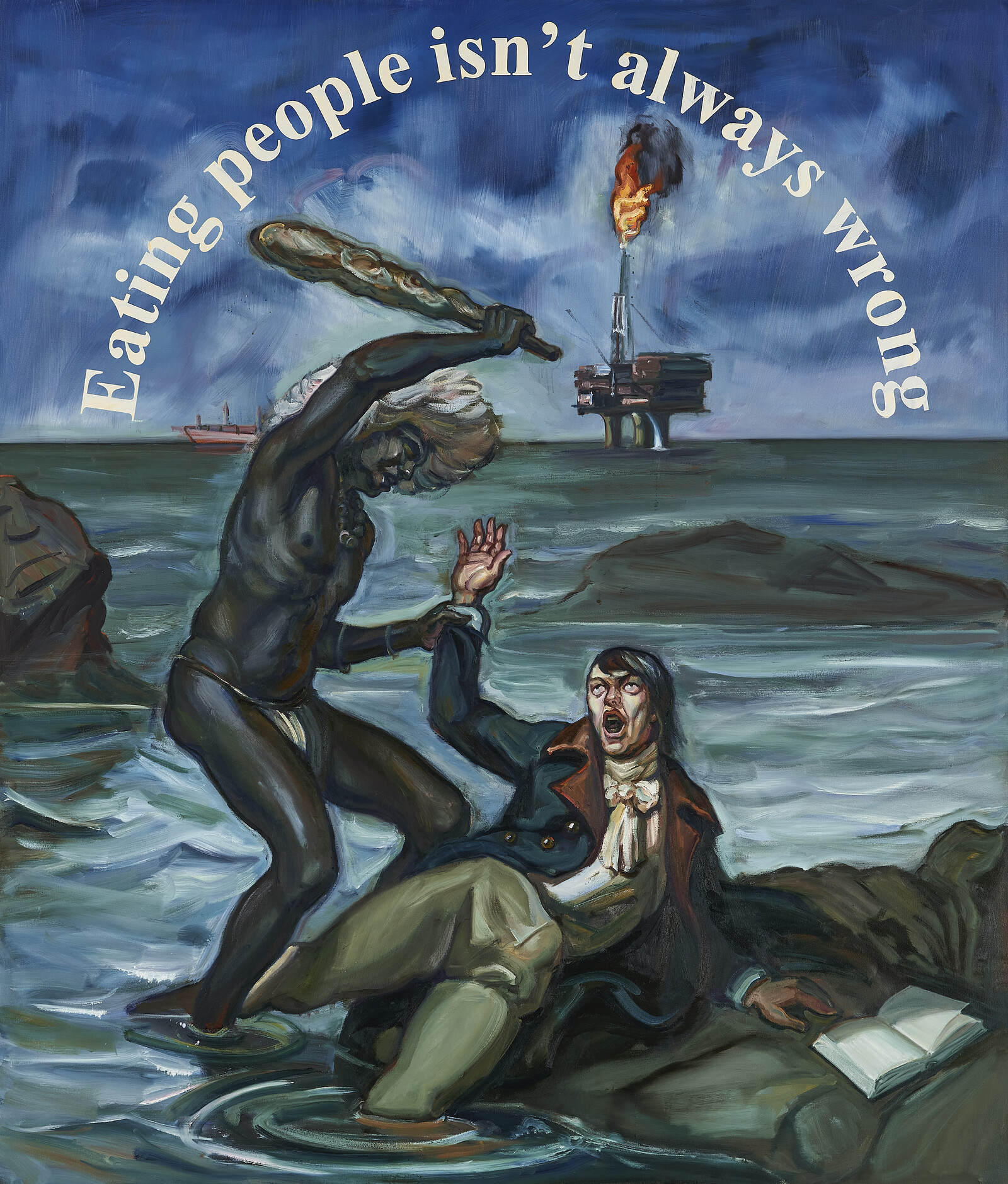

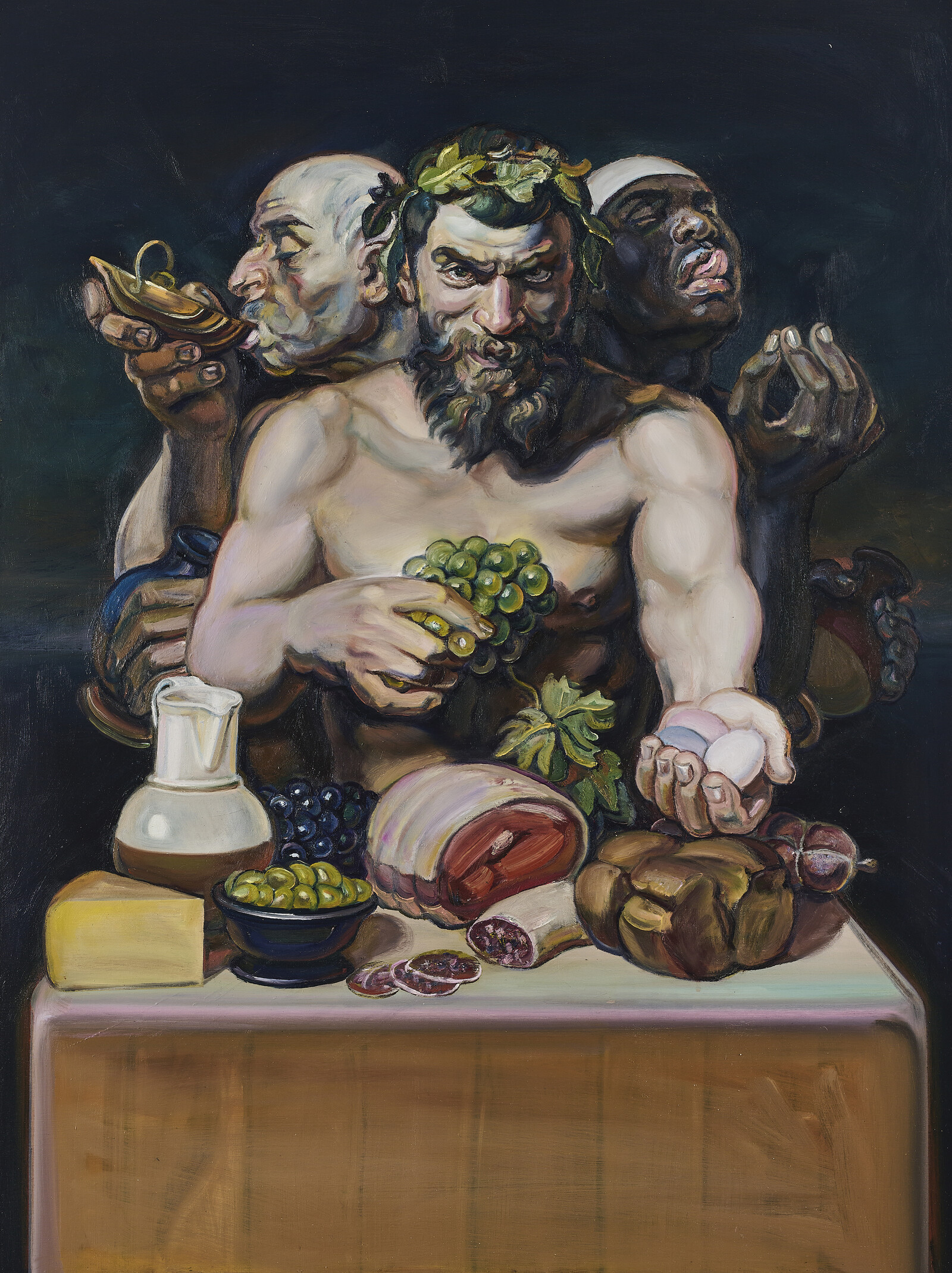

Phokela’s paintings not only narrate, they declaim. Probing the binary nature of South African life, Exciting Recipes (2015) presents a homespun white couple watching a blond accomplice attending to a well-stocked table of food and drink, this as a Black woman carves meat from a suspended carcass in a compartmentalized space also occupied by two men, their gazes fixed on their white counterparts. Raw meat figures a lot in Phokela’s work, as does fleshy white skin, which he attends to with care—his protagonists are specific, even as they are made to perform generalized ideas.

Original Sin (Inner Circle) (2021) revisits the originary Rubens composition, in Delft Blue, now with a pregnant figure enclosed in a pinkish halo at its apex. The Menzl stain remains, albeit as a dribble; Phokela’s iconoclasm is now largely sublimated in his figure compositions. In a 1772 lecture, Joshua Reynolds, a keen admirer of Rubens, remarked that his sensual forms could sometimes be “florid, careless, loose and inaccurate,” which is true of Phokela, too. But academic naturalism is not his ambition; rather it is the production of a dialogic and iconoclastic form of figure painting that directly and emblematically, with baroque flourish, speaks to our querulous present.

See Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution (London: Reaktion Books, 1997/2007), 198–9.

Himid’s Hogarth-inspired A Fashionable Marriage (1986) is included in the artist’s survey at Tate Modern, London, through July 3, 2022