From the darkness, a bright, circular spotlight illuminates a theater curtain. Searching intermittently along its folds, the light traces paths which uncover crimson underneath deep black. The curtain finally pulls upward revealing a moon of bright white.

The opening images of Mary Helena Clark’s By foot-candle light (2011) present viewers with a prototypical symbol of cinema-going, a moment of anticipation not typically found in a venue like London’s Laura Bartlett Gallery, with its white walls and light-leaking windows. Clark’s video is shown in an exhibition consisting of a single daily projection of five moving image works selected by British artist-filmmaker Beatrice Gibson. Though not a curator, like many artists working with moving images, Gibson has occasionally been put into the role of selecting films to show alongside her works. Previous instances of this have comprised combinations of the work of artist peers (like Clark and Laida Lertxundi) and important influences (Tony Conrad and William Greaves). This exhibition, under the framework of research-in-progress for upcoming films, functions in much the same way, and displays an understated yet impressive curatorial cohesion while at the same time being beholden to the peculiarities of transposing a cinematic presentation to a commercial gallery.

“Go on, look at me. I’ll kill you. Look at my eyes. Sometimes I stand in front of the mirror and my eyes get bigger and bigger.”

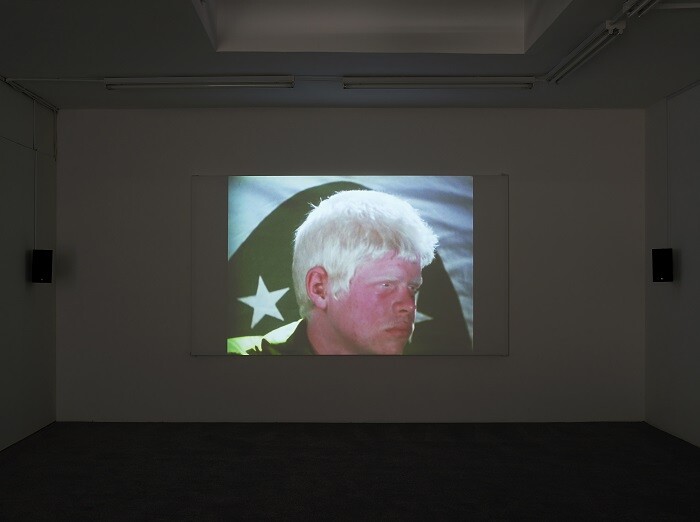

Evokation of My Demon Sister (2002) by Ellen Cantor is a short video that can be taken to represent Gibson’s program in whole: nostalgic yet contemporary films and videos that exorcise previously made materials through acts of ritual, trance, and hypnosis. An example of this détournement in Cantor’s work occurs as actress Christine Noonan delivers the above dialogue from Lindsay Anderson’s teenage rebellion film If… (1968). Simultaneously we see a montage of clips from Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976)—Sissy Spacek’s title character shatters a mirror with her gaze, causes a fatal car crash, and summons flames that engulf the stage of her senior prom—while Mick Jagger’s caustic synthesizer loop from Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969) plays over the top. Cantor’s Evokation reacts against Anger’s phallocentric work, harnessing its satanic energy toward a reclamation of the trope of the female hysteric. Showed consecutively on a single screen, the sequencing of the works functioned in a different way than if they were all separate, looping projections that viewers came to at their individual pace. Connections are made in sequence and each of them flows into the next. Cantor’s Evokation begins with the moon, calling back to Clark’s white spotlight, and ends with a mass of flames, a fire which roars through the first sequence of Michael Robinson’s 2013 video The Dark, Krystle.

“There was a fire in the cabin…I tried to leave but the door was locked. I died in that fire. I don’t know who I am.”

The Dark, Krystle, which reimagines the popular 1980s television series Dynasty as a baroque, melodrama-tinged Euro-horror film, harnesses the latent dramatic energy of its female actresses/characters towards a new spectral end. Robinson, Cantor, and Basma Alsharif’s works utilize dark, usually unforeseen energies in a hauntological manner from images, sounds, or—in the case of Alsharif, whose video Deep Sleep (2014) shows architectural ruins in Malta, Greece, and Gaza—places. That this screening represents a body of research for Gibson’s two upcoming 2018 film works—one of which is an adaptation of an unrealized Gertrude Stein film script—suggests that these spectral energies are not only to be read aesthetically but toward the task of realizing a project with unfulfilled potential. Thus, the inclusion of Anger’s Invocation represents not only an ur-text, a genuinely satanic experience while the other works reach toward it, but also a career of half-realized projects, lost films and production nightmares that stand against the sanguine Magick Lantern Cycle works which he did accomplish. By putting this group of works into a public discourse through the form of an exhibition, Gibson suggests some of their techniques as potential avenues toward her works in progress, creative approaches to adaptation, or possibilities that hypnagogic re-imaginings of older texts can enable.

A walk through an ancient, crumbling temple, the filmmaker dressed in white and holding a microphone leads to a violent yellow/blue flicker. The perspective shifts to a first-person view of the filmmaker’s body emerging from repose on an ocean cliff. She stretches her hand in front of the camera, touching the horizon with her finger, causing a flash frame to transport her to another location.

The program raises familiar issues around the slippage between black box and white cube. The 45-minute screening, exhibited with excellent projection and sound, was shown once daily at 4 p.m., with ample light leaking into the viewing area. One wonders if it might have had a different impact as an event in one of London’s many cinema spaces for artists’ film, or how the program functions as a modest, non-profitmaking project in a commercial gallery. The trade-offs—free admission but limited showings, excellent image and sound but a light that washes out the picture—can be overlooked in a screening that teems with darkly affective potential.

“ZAP YOU’RE PREGNANT THAT’S WITCHCRAFT”