Styling itself as the “oldest short film festival in the world” as well as, rather less memorably, the “largest festival in North-Rhine Westphalia,” the annual gathering of filmmakers and producers at Oberhausen offers the latest opportunity to reconsider questions that have shadowed the festival almost since its inception: what do we mean by short film, and how does it relate to the wider fields of cinema and contemporary art? As the classification has been subsumed into “moving image” and migrated online and into the gallery, should we now think of it as a testing ground for approaches that might percolate into mainstream film-making, another channel through which artists might express ideas not confined to a single medium, or a discrete art form with its own histories and non-transferable stylistic characteristics? In proposing rather vaguely that it might be “the experimental field on which future film languages are formed,” the festival’s own literature betrays some of the anxieties arising from the attempt to corral proliferating styles, formats, and economic networks into an overextended category.1

First impressions of the International Competition were that its curators were perhaps too eager to accommodate all these possible interpretations, and several more besides. Entries were divided into screenings presenting everything from five-minute-long experiments in cinematic abstraction to straight documentaries lasting the best part of an hour. If any logic was discernible in these groupings, it was that the works should be so diverse in register and subject matter that audiences would not be allowed to settle into the patterns of light snoring that must afflict all such festivals (it was not, predictably, entirely successful in this respect). Thus a stop-motion animation addressing the destruction of Indigenous communities by Christian missionaries through the allegory of a misunderstood bear (Terril Calder’s affecting A Bear Named Jesus, 2023) was juxtaposed with a documentary about traumatized veterans of the kind that might until recently have been aired on free-to-air television (Katie Davies’ Return Belong Prosper, 2023) and a portrait of a dead Viennese artist through a guided tour of his apartment (Sasha Pirker’s will have been, 2022). At its weakest—as in the inclusion of the AI-generated and dispiritingly vacuous Let’s Be Friends (2022) by Arno Coenen and Rodger Werkhoven, presumably in the hope that it ticked the box marked “relevance”—the sense was of a festival so desperate to cover every base that it risked undermining the commitments on which its reputation is established.

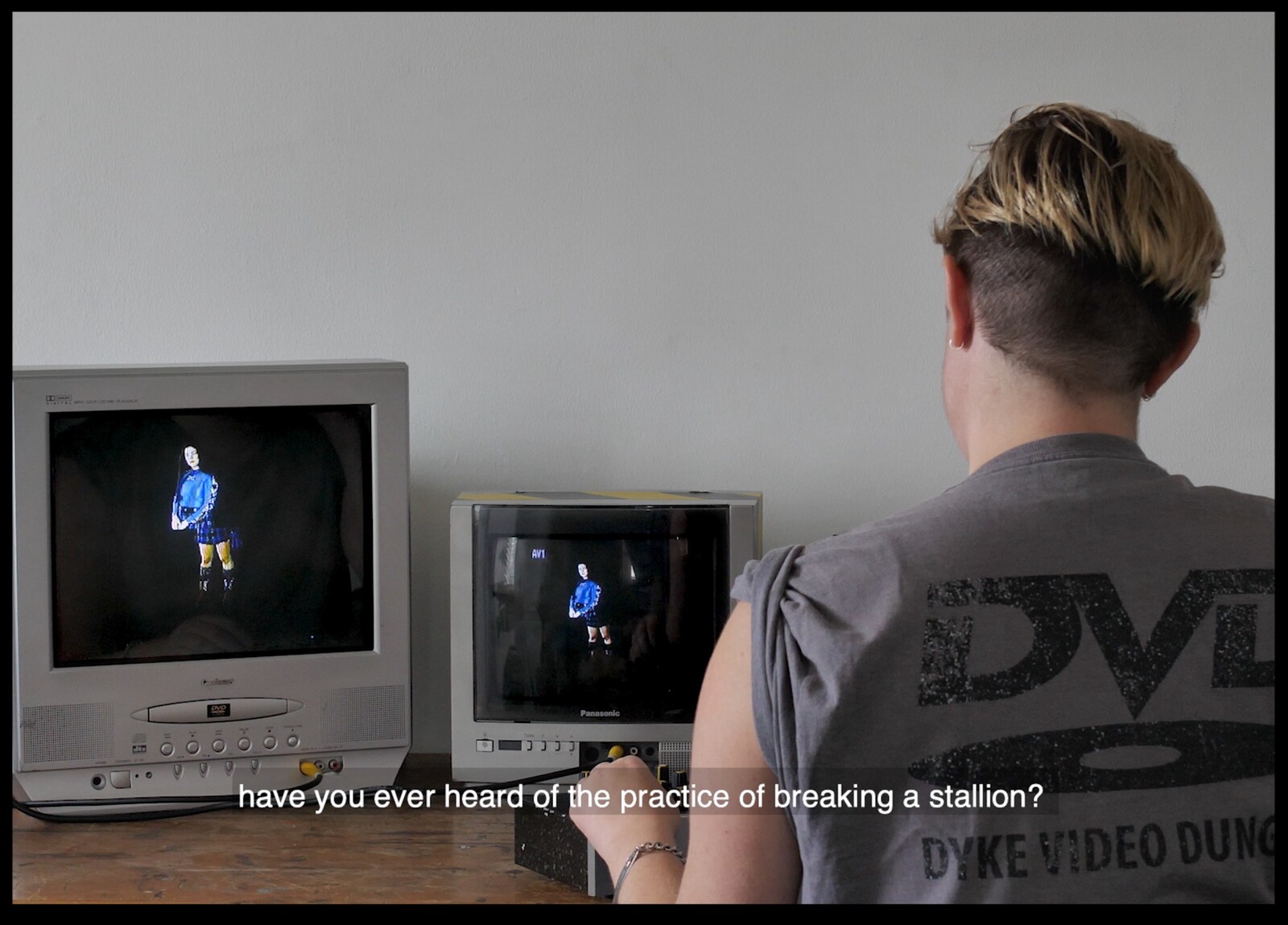

At its most successful, however, the program revealed the field of creative possibility opened up to filmmakers by the new affordability of sophisticated recording and editing equipment. As the music industry has been overtaken by the genre of “bedroom pop,” so many of the most imaginative contributions to the festival might be characterized as “bedroom video,” made by filmmakers working on their own, in their homes, and outside the established economies. Sweatmother’s Untitled (2022), to take one example, stages a conversation between the artist and a digital avatar programmed to represent their hyper-feminized “other.” That this video of someone talking to their computer screen about the performance of gender was so compelling is testament to the quality of a script that weaves passages from Paul B. Preciado and Walt Whitman into a loosely confessional narrative. By contrast to this lo-fi intimacy, Yuri Semashko’s Garbage Head (2022) employs a comparably minimal cast of the artist, his dog, and an enchanted papier-mâché head to build a remarkably expansive and wickedly entertaining fairy-tale world. As divergent as these two examples are in their themes and aesthetics, they are united by the traditional constants of good filmmaking: an emotional and intellectual commitment to the subject matter, an understanding of how to compose a frame, and attention to the formal characteristics of the medium.

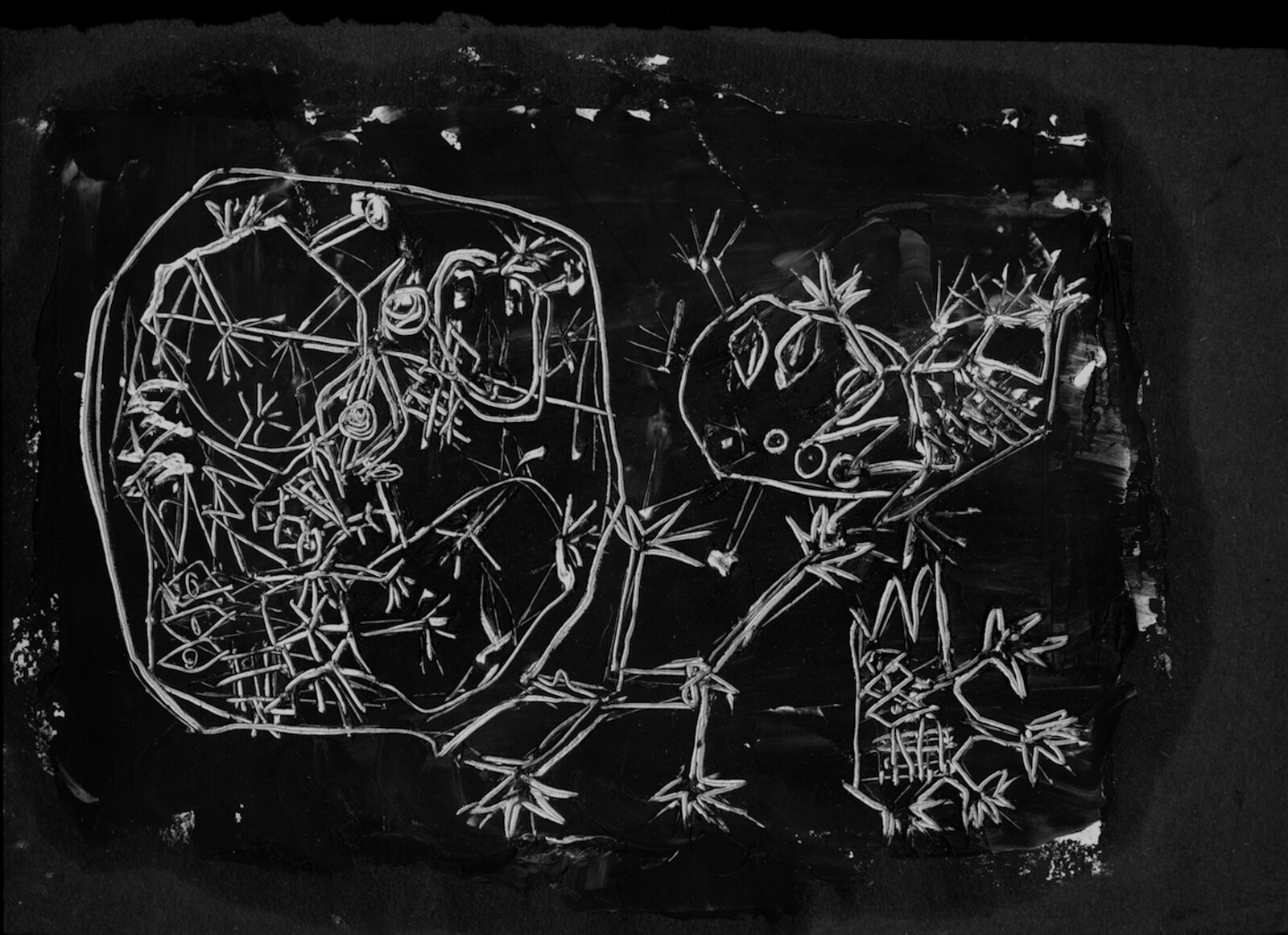

A more convincing case for short film’s status than as a showcase for Dall-E’s creative aspirations might be constructed from that latter point. It is striking, for instance, how many of the best entries take advantage of the form’s inherently fragmentary nature to represent the nonlinear experiences that are characteristic of trauma. Lori Felker’s beautifully restrained staging of a routine day in the training of medical professionals unfolds into a meditation on transference, empathy, and performance (Patient, 2022); Jayne Parker’s vanguardist setting of a series of harrowing line drawings made during her teens to a composition for cello performed by Anton Lukoszevieze gives shape to the ways that past traumas might irrupt into the present (Secondary Action, 2023). Teboho Edkins’s Ghosts (2023), meanwhile, splices together photographs taken in a South African settlement in 2006, spectral footage of the last of a nearby tribe of elephants, a young white girl relating her visions of the dead, and scenes from a Black evangelical church service to construct an account of historical displacement and environmental disruption that feels truthful precisely because it offers no cathartic resolution or easy moral takeaway.

Similarly, the elliptical possibilities of short film are well suited to critiquing a culture in which images are put to the service of reductive narratives expressly designed to appeal to consumers by affirming their prejudices. Nicolás Pereda’s Flora (2022), for instance, responds to the difficulty of representing narco-trafficking in Mexico by focusing on the details elided in the production of stories that either heroize or demonize their protagonists. These loops, absences, and lacunae serve a purpose at once epistemological and ethical: “the danger of stories around contemporary conflicts,” as the voiceover puts it, “is that they usually have very clear beginnings and endings, which make us believe we understand the problem in its totality.” If short film can reacquaint viewers with the fact that we must work harder to ascertain knowledge than relying on the pleasingly simple and reinforcing versions of truth generated by contemporary media platforms and the mainstream culture industry, then no more handwringing over its continued relevance is necessary.

Only a fraction of the entries to this year’s competition, to illustrate the point, would qualify as “short film” under the strictest traditional definition, with the majority shot digitally.