Just before midnight on February 29, 1960, an earthquake hit the Moroccan city of Agadir, killing between 12,000 and 15,000 people—roughly a third of the city’s population. As many were injured; at least 35,000 were left homeless. Yto Barrada’s “Agadir,” in The Curve gallery at London’s Barbican Centre, invokes the disaster in oblique and poetic ways across drawings, audio recordings, collage, and film. Despite the breadth of media employed, this is a show that lacks the depth of historical context one might expect from such a weighty subject, compelling viewers to keep reading, watching, and learning after they’ve left the exhibition, in order to fill in the gaps.

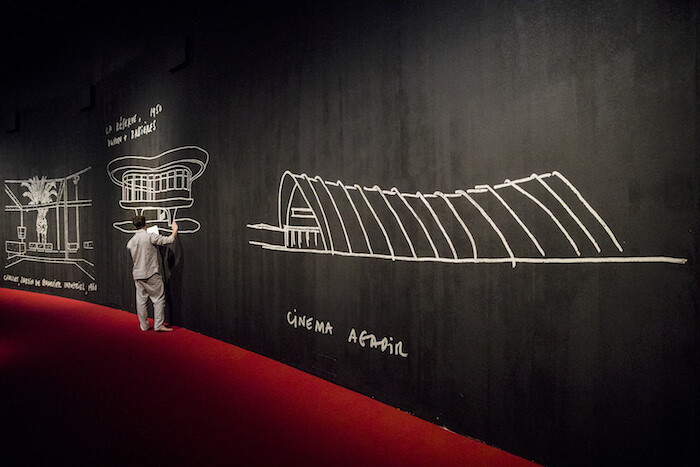

Entering the dim gallery was exciting. Its dark lighting and dramatic colors—the long curving wall painted black, the carpet beneath it blood red—recalled the set of a camp Italian horror film. (The cinematic influence is in keeping with the artist’s broader practice: in 2006, Barrada founded the Cinémathèque de Tanger, an independent project that, operating from Tangier’s Cinema Rif, is dedicated to the local and international promotion of independent Moroccan film.) On the Barbican’s curving wall are sixteen large drawings, “Untitled (Agadir)” (2018), executed by scratching broad white lines from the black paint. Referencing modernist buildings, they resemble architectural sketches crossed with children’s chalk scrawls. Nearby are pieces of rattan furniture, collectively titled “Conversation Chairs” (2018). Speakers attached to the chairs play extracts of Moroccan author Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s 1967 novel Agadir, concerning the earthquake and its aftermath.

Although Pierre Joris’s English translation of the French is explosive and macabre, viewers would need superhuman ears to hear it. Unable to catch the muted narratives, I jammed my phone into the speaker and pressed record. Khaïr-Eddine offers aching accounts of the earthquake. One survivor finds “one of his wife’s finger joints” and saves it. Others plead for aid in “this rift where Spain [France’s partner in colonizing Morocco] has left its horseshoe rusted.” Yet such phrases disappear into sonic faintness, echoing the visual confusion created by a large mobile of rattan sculptures (Danse macabre (My-City-Knife-of-the-Sun), 2018), which dilutes Barrada’s subject into a vague, decorative interest.

A nearby illustration (Child Drawing, undated) is credited to Barrada and her brother. Depicting a hillside town, with flat buildings, palm trees, and cars, the scratchy white illustration operates like a microcosm of the larger drawings and is indicative of the artist’s aim to string viewers through her work using clues and citations. I was left to wonder how this drawing relates to Agadir and the catastrophe that befell it. Barrada brings the catastrophe into discomfiting contact with whimsical childhood imagination. But the effect is more mischievous than moving.

If Agadir today seems a wonder of brutalist architecture (not unlike the Barbican Centre), its construction was facilitated by this disaster. This conflicted history may explain the ambiguous approach of Barrada—who was born in France, grew up in Tangier, and later returned to Paris to pursue her studies—to her subject. Anagramme Agadir (Agadir Anagram) (2018), a documentary about the earthquake stitched together with black-and-white newsreel footage, offers the clearest window onto the event. Projected near the exit, however, it comes as a late attempt to infuse this playful show with gravitas.

Indirect refractions of catastrophe are often more suited to their subject than sensationalized depictions. While the former put stress on thought and imagination, the latter satisfy—if only fleetingly—the desire for catharsis. W. G. Sebald (1944–2001) exemplified the former. His novels resound with fugitive echoes of European trauma, as characters encounter old friends and auratic architectures. Barrada also uses architecture as a conduit of memory, while her playfully dramatic approach—the mood lighting, the red carpet—avoids indulgent ruin-pondering. Yet her use of so many mediums leaves viewers perplexed, shuttling between ersatz lenses of memory.

Artists have long been acknowledging viewers as active participants in the construction of meaning, yet “Agadir” suffers from an excessive reliance on this approach. Surely a topic so grave merits further historical elucidation and a more vivid, impactful affect? It may be that the fortnightly performances—during which actors from London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama read sections from Khaïr-Eddine’s novel while interacting with the rattan sculptures—weave the show into a more cohesive experience, or lend it the corporeal weight it otherwise lacks. But most viewers, inevitably, will not encounter them.

A suite of collages (“Untitled (collages),” 2018) suffer especially: peripheral material in an over-stretched conglomeration of artistic methods. Comprised of decorative patterns and photos paired with typewritten texts detailing the earthquake’s effects, these touching works resemble scrapbook entries. But that’s just it—they’re movingly humble pages. They drift confusedly in this show: a place that became no place for trying to be everywhere at once.