Boston Center for the Arts, Boston

June 29–August 30, 2020

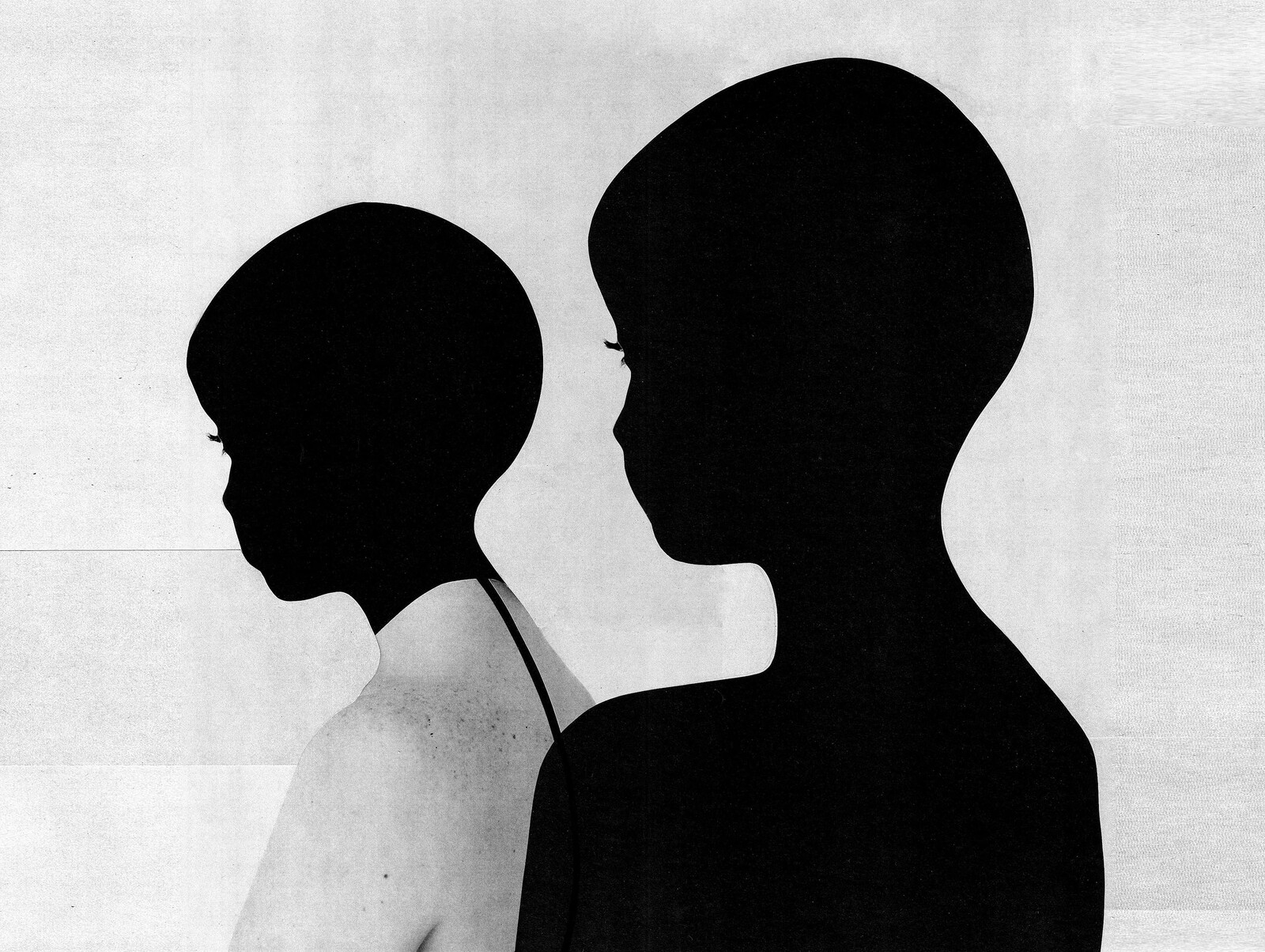

“A Language for Intimacy” is an online group exhibition, curated by Amanda Contrada and Terence Trouillot, addressed to the notion of intimacy. The project is set up as a dialogue between nine artists and nine writers. Each page centers images of an artwork at the top, with an interpretative meditation below it. To take one example, Sougwen Chung’s Corpus VII, from the series “(distance) in place” (2020), is a drawing made using a robotic arm, in which Claire Voon sees “the poetic promise of mechanical and artificial systems to imagine forms of closeness in an increasingly estranged world.” Voon’s observation could be extended to the project as a whole. Contrada and Trouillot have assembled a portrait of entanglement between humans, and our entanglement with the technologies of perception we use to try to reach each other. What emerges is the sense that intimacy is in crisis, infused with a profound exhaustion and uncertainty.

In late March 2020, Paul B. Preciado published a short piece in Artforum describing the moments after he emerged from the sickbed in an empty Parisian apartment. The last paragraph struck me as a particularly apt analysis of intimacy during the present pandemic. He wrote a love letter to an ex, addressed the envelope, donned protective equipment, and descended to the entry hall of his building. In Paris at that time, it was impossible to leave one’s house without filling out a form stating the reason. Physically unable to step out into the street to post the letter, he dropped it in a trash bin huddled in the back courtyard and returned to his empty apartment, meticulously stripping off his protective gear before entering. “I went back to my computer and opened my email: and there it was, a message from her entitled, ‘I think of you during the virus crisis.’”1 Preciado’s experience stages the same impossible contradiction that Contrada and Trouillot address in “A Language for Intimacy”: if we can no longer reach for other in the flesh, how will we touch one another? Will the new forms we find for intimacy be adequate to render our exhaustion and our loneliness?

The website on which “A Language for Intimacy” is presented is precise and minimal in design, like the email Preciado finds from his ex. Large white script against a black background elucidates a series of individual project pages that nestle into each other on a banner tab at the bottom of the page. It works as an online exhibition portal because it does not indulge in the idea that an enthusiastic exploration of digital space will yield new insight into the human condition. The graphic design is firm on that point: we are living through an emotional crisis that is also a political and economic disaster, let’s just be real about that. Instead, the project suggests that the role of art right now is to provide some basic infrastructure to maintain the connections we will need if we are ever to emerge from our homes, should we be lucky enough to have them.

Ladi’Sasha Jones writes in response to Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste’s performance XXX-XXX-XXXX (2020), which is conducted over a landline he has installed in his home, that anyone can call over the course of the exhibition: “The curved shell of the handset in my hand. The click of the hook switch as it interrupts the dial tone. Stuffing my fingers into the coils of the cord. The resounding beep that came from pushing the buttons.” As Jones’s essay reveals, the performance’s impact lies in the way it shifts the viewer/listener’s experience of connection. Those of us who are old enough remember the way a landline held you in place as you spoke on it. Even when I connect from my computer in Rotterdam via a Skype account, I am suddenly aware that somewhere in the process of calling my voice lands in a wire that actually threads itself through the walls of someone else’s home; I feel the weight of the intercontinental distance, and the extensive infrastructure required to connect us.

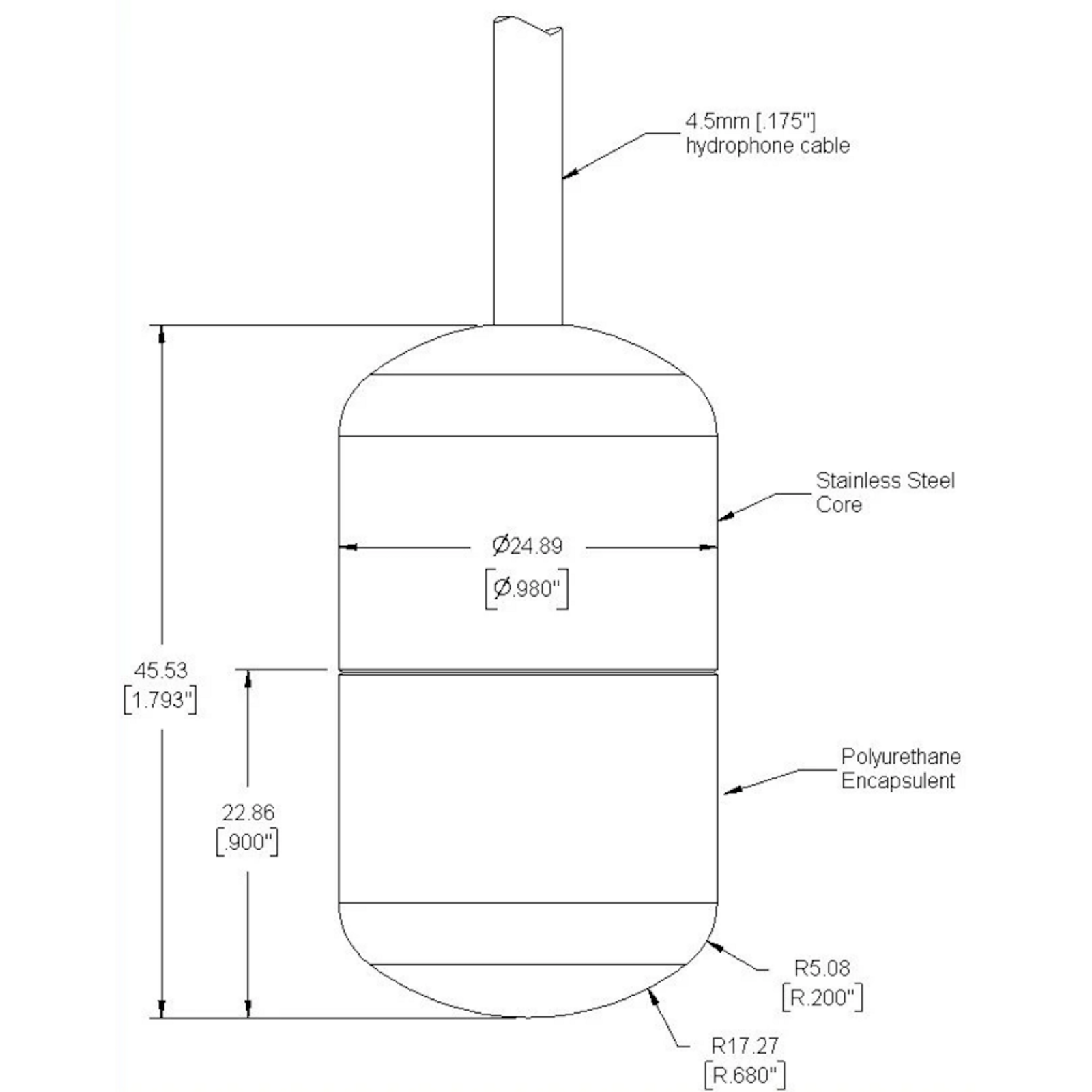

“What does it mean to listen to a body inside another body?” Amelia Rina asks of Rachel Devorah’s sonic work, radiant drift (2020), which is composed of hydrophonic sound captured from within the artist’s pregnant womb. I click to play the 18-minute piece late at night, alone at my desk, and am immediately set on edge. Its high-pitched modulations are a jarring reminder that the kind of intimacy that exists between a mother and their fetal child is intense, visceral, painful for many, and yet the origin of all other patterns of attachment. The work also begs another question: what responsibility does listening to a body inside another body entail?

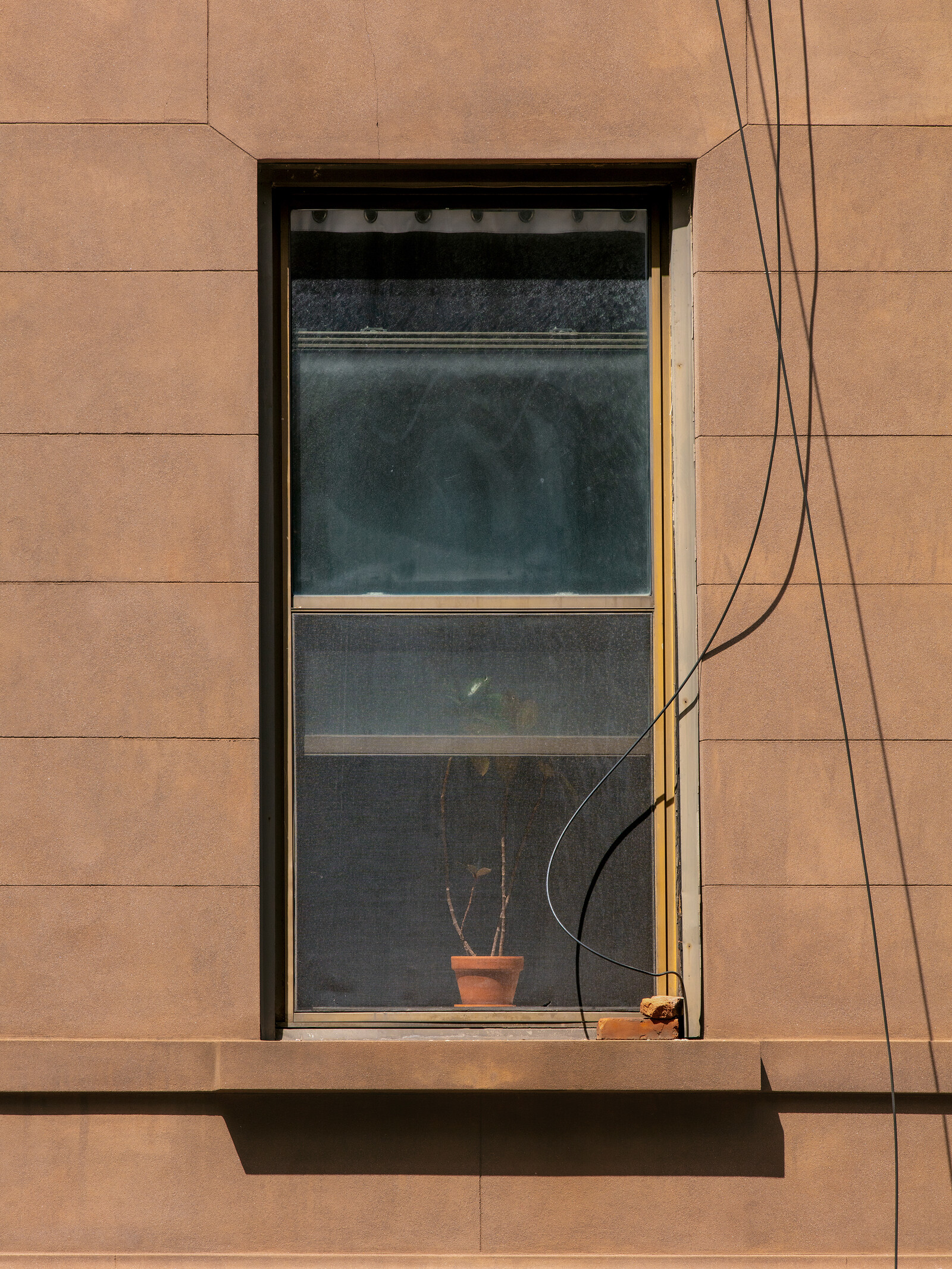

Contrada and Trouillot suggest, both through selection and the dialogue format, that intimacy today is as entangled with the responsibility to listen deeply as it is with mechanical and digital interfaces. It is a question that is inextricably bound up with that other pandemic, racism. “Did you see the Black woman in her apartment? Do you notice how elegantly she reclines?” Erica N. Cardwell asks the viewer of a photograph, Not yet titled (After Live, Laugh, Love) (2020) by Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. “Do you notice how she does not look at you?” Cardwell insists that the focus remain on this person’s exhaustion, the potential for her rest. Someone has freshly painted the windowsill behind her, white brushstrokes straying beyond the molding, which contributes to the overall sense that this is a snapshot taken after the day’s work and at the edge of sleep. “Please continue to see her,” Cardwell writes, “please let her close her eyes.”

Paul B. Preciado, “The Losers Conspiracy,” Artforum (March 26, 2020): https://www.artforum.com/slant/the-losers-conspiracy-82586.