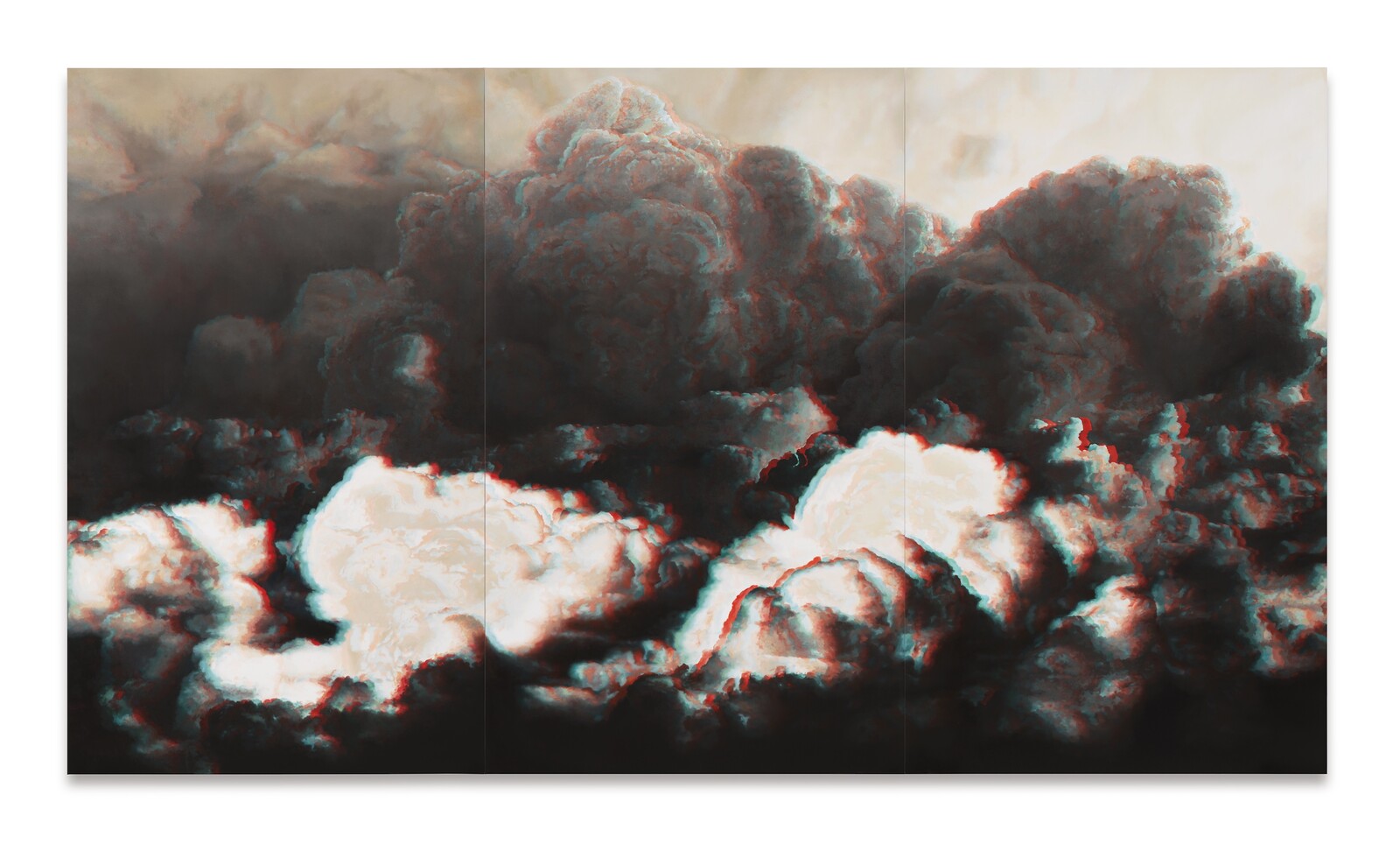

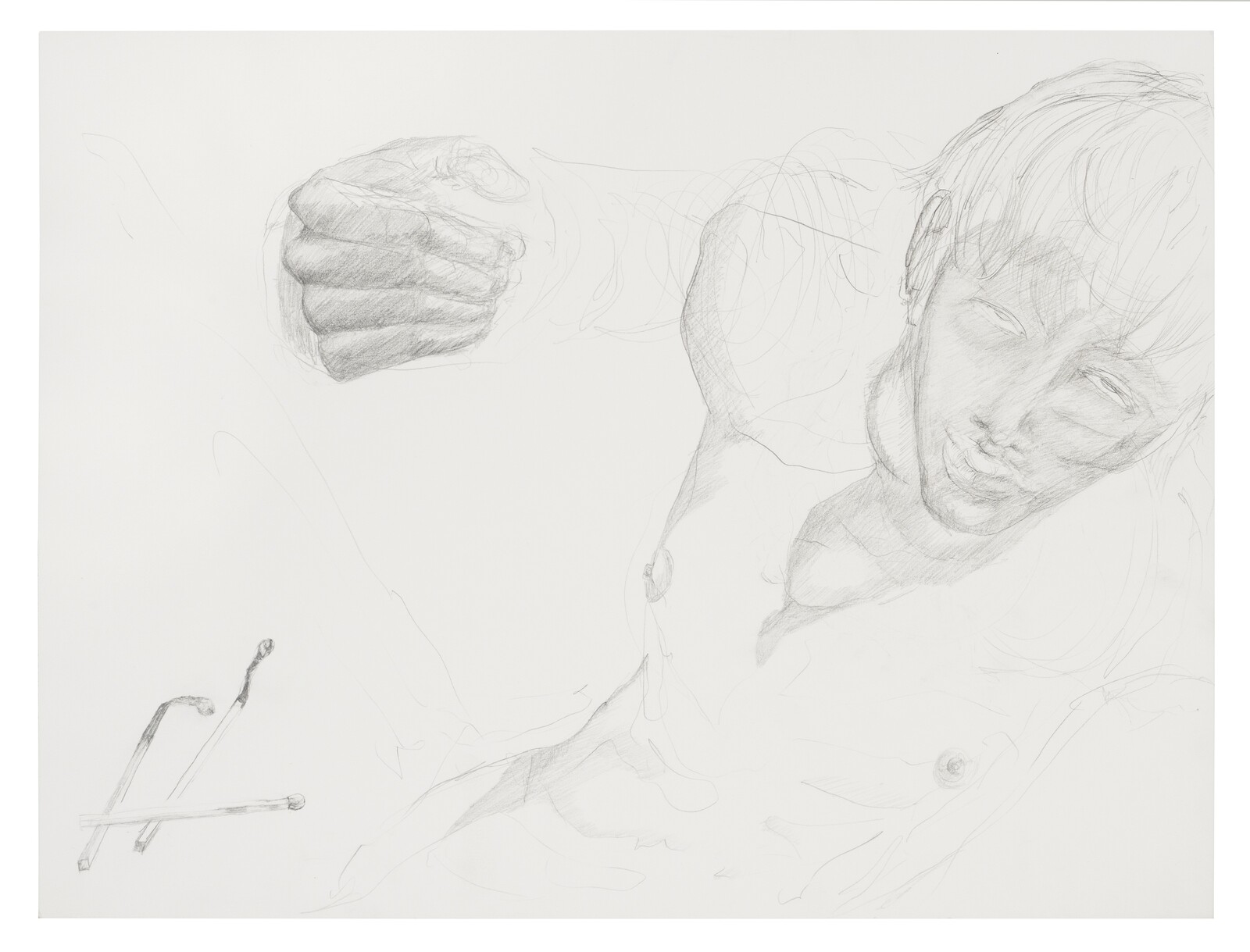

“AVATAR” is an installation featuring rows of industrial lockers, cored concrete blocks, a large, three-panel painting of clouds, figurative drawings, and new additions to Anne Imhof’s series of “Scratch Paintings”—large aluminum panels coated in custom automobile paint with patterns scratched into them by the artist. While no performance will be held here, it is impossible not to think of it as a set absent the actors—which, given the function of lockers and the potential density of bodies in a locker room, isn’t far-fetched, even if we bracket the German artist’s fame as a dramaturge. The lockers containing concrete blocks as a way of staging giant, slightly abstracted car doors is almost too literal if you have even a glancing, film-based familiarity with industrial production. The untitled cloud painting is compelling—beautiful in a Monet’s waterlilies sort of way. The drawings—mostly hung in a back space that functions as an office—are likely there so people have something to buy. The show is fine. Imhof is a talented painter and draughtswoman. One could leave it at that if it weren’t for the ghosts of bodies that might use the lockers on the way into a General Motors plant.

Imhof continues to describe herself as a painter, but she is best known for several elaborately choreographed performances. Faust, a Gesamtkunstwerk that won the German Pavilion the Golden Lion at the 2017 Venice Biennial, was performed by a cast of attractive, stone-faced, mostly white people including Imhof herself and her long-time collaborator, the artist, musician, and Balenciaga model Eliza Douglas. The German Pavilion is a Nazi-era building in and around which Imhof installed a raised glass floor, eye-level platforms that resemble jail-cell beds, hurricane fencing, and some Doberman Pincers. Her previous production, a three-part opera called Angst (2016), involved the same core of collaborators (Douglas, Billy Bultheel) who sang, dressed, and moved in a manner that signified boredom, alienation, and emotional absence in spaces chosen to reflect or amplify these aestheticized feelings, while drones zoomed around over their carefully posed and contorted bodies. The performers are talented; the music is beautiful; the choreography combines unlikely bodily positions with mundane activity; the sets take the given architecture into account while intervening with legibly contemporary spatial languages.

One might get the impression that the artist is making a pointed—even overwrought—political statement. But most of what Imhof has to say about her own work is in the vein of “art for art’s sake.” Of the performance of Faust, she explained to Hans Ulrich Obrist during an interview at the Beyeler Foundation that the bodies are another way to explore her interest in abstraction. In an interview with Adrian Searle of the Guardian about her 2019 performance Sex at Tate Modern, she describes the actions of a central performer as that of a flaneur, “who is only ‘entering for the entering.’” In the same interview, she expresses frustration with the term Gesamtkunstwerk because she doesn’t like being compared to Wagner. When asked by Naomi Rea of Artnet about the fascist aesthetics of many of her performances, she replies, “That’s bullshit. My background is very much an anti-fascist one.”

Despite the article’s inference from this defensive response that Anne Imhof is an “anti-fascist artist,” anti-fascism doesn’t seem to be something that Imhof is consciously taking into account. Instead, the aesthetics of surveillance, incarceration, alienation, and anger are being unselfconsciously reproduced as extremely sexy spectacles. It is difficult to locate the point at which an art object tips from critical and engaged into complicit and offensive—which is why, I suspect, most writing about Imhof is so weird and evasive. Furthermore, when writing about art featured in national pavilions at the Venice Biennale, it is difficult to be critical without dismissing the whole enterprise as a disgusting, elitist activity organized around bad faith gestures towards political change and the aestheticized consumption of other people’s suffering. We either have to shut the whole thing down or draw a line somewhere.

Imhof’s work—which implies that the problem with drones, fences, guard dogs, and prisons used to surveil, capture and dehumanize refugees, poor people, and disenfranchised minority populations is actually healthy, wealthy (again mostly white) ennui—is where I think the line might fairly be drawn. If the performance of Faust is sufficiently complex to be exempted, you might take a look at the album cover, which features a fist clenched in a gesture of solidarity that is so wildly at odds with the content of the work that one has to admit that there is something fishy going on here. Art that is politically ambiguous is important: there are other mediums more suited to clear political statement, and an expectation of clarity or legibility in artworks is a political position in itself. But are we really going to talk about, as Artforum’s David Velasco does, Imhof’s “radar for something that is not tangible” and compliment her ability to calibrate “different levels of intensity” when something very tangible and obvious is being referenced? And when the intensity is obviously derived from real and urgent political problems?

Sure, androgyny is potentially interesting, one can always say something about subjectivity, anomie is not irrelevant and, given that I have no firsthand experience of the endurance aspect of watching the live, four-hour performance, I will assume that I am missing something there. But the overall impression that one gets from documentation of these performances is of behind-the-scenes footage from a 1994 CK One commercial. As someone who is just about Imhof’s age, I recognize—as I think I am supposed to—what Velasco referred to as the “supremely entitled cool” conveyed by the runway grunge of my adolescence. Headbanging features in the performances as well as in the commercial. And I am not the first to note the resemblance of the German Pavilion to an Apple Store.

The comparatively modest show at Gallery Buchholz is, similarly, deriving its intensity and its content from industrial production. The emptiness of this locker room might speak to capital flight. The gesture of scratching a desire for sabotage. Keying cars as they came down the line was not an unknown “negotiating” tactic in US factories. The concrete blocks are the stuff of cheap institutional architecture: essential for buildings in places we do not care about, like rustbelt elementary schools. The clouds, beautiful and metallic, might call to mind environmental degradation in the register of the industrial sublime. I don’t know what Imhof has to say about this installation. Maybe it reminds her, like the recent nature mortes, of being in a band. But she has yet to speak publicly about low-wage workers, changing in a locker room because their job is dirty and dangerous (which is better than the job simply disappearing), environmental degradation, or the total devastation of communities wrought by capital flight.

We currently inhabit a world where some people are allowed to make art at the expense of the exploitation and early death of large portions of the population. Capitalism is not corrected—it may not even be challenged—by the art that it produces. This is not Imhof’s fault. We are all stuck inside of this system and, as her art accidentally points out, this is terrible even for the people who benefit most from gross inequality. Still, there is something especially unethical in the unacknowledged appropriation of explicitly political symbols and histories. Imhof’s work has the effect that it does because of its content—an array of symbols, objects, and references that cannot be detached from their non-art signification. To professionally benefit from historical and ongoing political struggles without acknowledging them is a form of symbolic suppression and violence that is surprising even in the context of the supremely cynical universe of art-stardom.

If you are going to use industrial workers, prisoners, and refugees as your subject matter and place symbols of solidarity among the oppressed on your album cover, you can, at the very least, acknowledge their presence in the world that you inhabit together.