“Video is everywhere,” begins the wall text at the entrance to MoMA’s largest video show in decades, as if on a cautionary note. Equally, to borrow an aphorism from Shigeko Kubota, subject of a recent MoMA exhibition: “Everything is video.” (It is worth noting that Kubota said this in 1975.) In tracing the evolution of video from its emergence as a consumer technology in the 1960s to its present-day ubiquity, “Signals” covers a dauntingly vast sixty-year span. A lot happened—not least to video itself—in the years separating the Portapak and the iPhone, half-inch tape and the digital cloud, and as the material basis of video changed, so too did its role in daily life.

This sprawling, frequently thought-provoking show proposes a path through these dizzying developments by considering video as a political force. In their catalog essay, curators Stuart Comer and Michelle Kuo call the exhibition “not a survey but a lens, reframing and revealing a history of massive shifts in society.” Not incidentally, this view of the medium—as a creator of publics and an agent of change—is in direct contradiction to a famous early perspective advanced by Rosalind Krauss, who in a 1976 essay wondered if “the medium of video is narcissism.”1 Seen in this light, Song Dong’s Broken Mirror (1999), on view in the first gallery, acquires a neatly symbolic function. In Song’s four-minute loop, one Beijing street scene after another is revealed as a reflection when a hammer enters the frame, smashing the mirror to expose an entirely different scene behind the glass, often startling bystanders who direct curious gazes at the camera. The mirror-reflection that was, for Krauss, inherent to early video’s operations vanishes in an instant, giving way to an altered social situation, a more complicated reality.

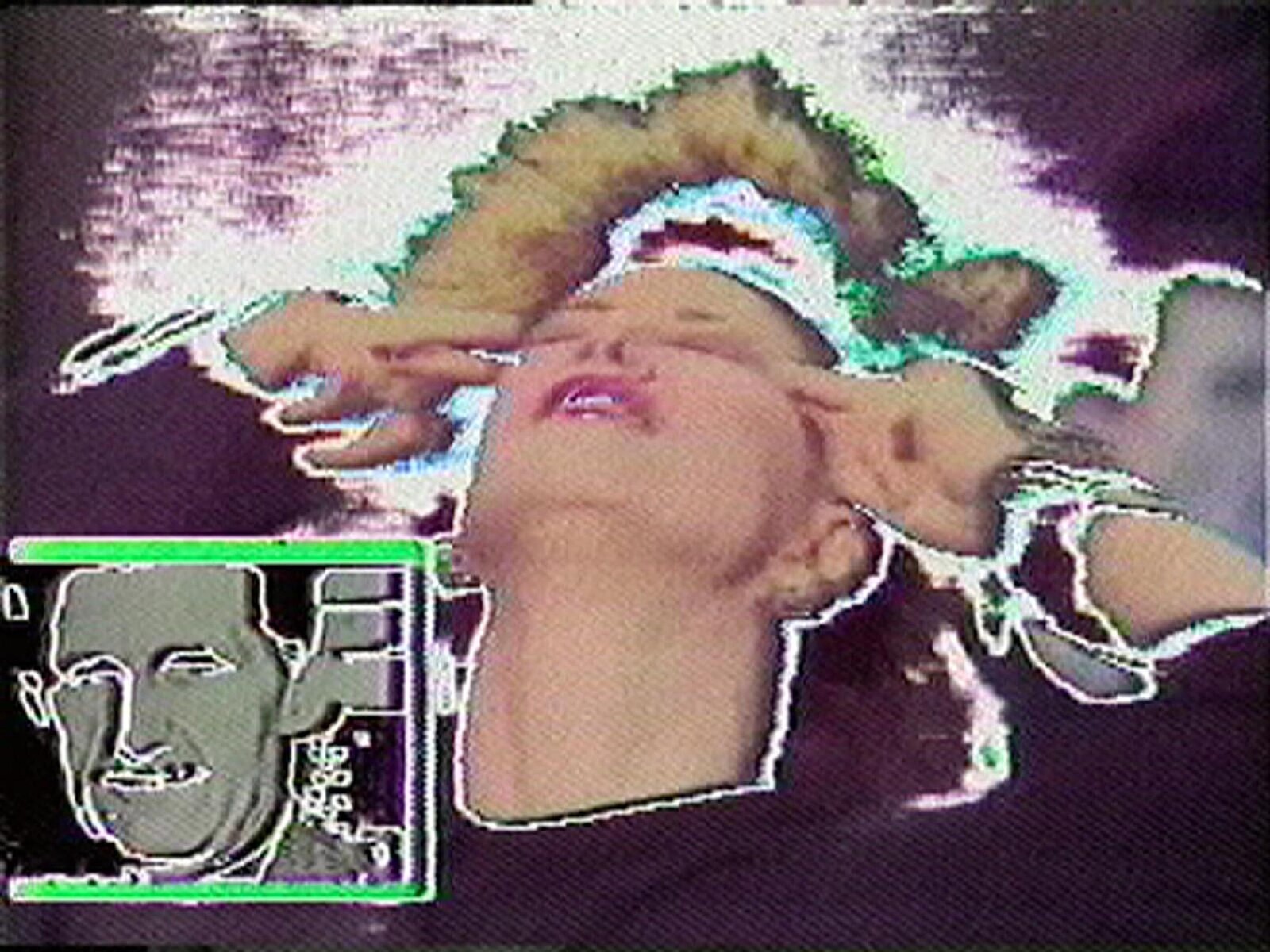

Occupying MoMA’s sixth floor galleries and spilling over onto an online channel, “Signals” includes more than seventy works, drawn largely from the museum’s collection, and running the gamut from single-channel tapes to multi-screen installations. The multiplicity of forms speaks to video’s adjacency to performance and conceptual art, and also to its eventual absorption into the broader categories of multimedia and digital art as well as artists’ cinema. Many of the pieces here were conceived for the gallery space, but a significant number have also circulated on television, in cinemas, or on the internet. The plasticity of the medium is pronounced throughout, evident in the glitch and ghostly decay of old analog tape, the synthesized distortions of Nam June Paik and other formalists, and the increasing malleability of the video image as it is coupled with CGI, game technology, or AI software.

The show’s notion of politics affords an alternative genealogy, bypassing many of the usual suspects who might otherwise populate a decades-spanning video exhibition. Conflict zones, historical cusps, and social movements are well represented, in works that encompass acts of witness and testimony, performance and protest, allegory and ethnography. Many share an oppositional stance, and “Signals” suggests that one way to tell the story of video is to note its many adversaries, the systems and structures that this most viral of formats has attempted to circumvent or infiltrate: broadcast television, corporate media, government repression and censorship, surveillance technology, the carceral state, and various regimes of visibility that have shaped and skewed our understanding of the world.

This exhibition captures the early promise of video in an array of works that seize on the nascent technology’s ease of recording, playback, and transmission relative to film. The documentary impulse, prizing vérité immediacy and spontaneous vox-pop testaments, is strong in the late ’60s and early ’70s—in electrifying footage of Fred Hampton, interviewed in Chicago in 1969 by the Videofreex collective weeks before he was murdered by the police, or in TVTV’s guerilla foray behind the scenes of the 1972 Republican National Convention, Four More Years. Pre-internet telecommunications experiments reveled in the wonders of simultaneity: for their “Send/Receive” project (1977), Liza Béar and Keith Sonnier secured the use of a NASA satellite link to create a live feed between artists in New York and San Francisco; with Hole in Space (1980), Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz staged a proto-video chat, establishing real-time interaction between public spaces in New York and Los Angeles, to the delight of unsuspecting passers-by who happened upon screens showing their counterparts in the distant city at life-size. Fujiko Nakaya’s Friends of Minamata Victims - Video Diary (1972) documents the eighty-first day of a sit-in at the Tokyo headquarters of the Chisso Corporation, responsible for a wastewater discharge that caused widespread mercury poisoning. The tape concludes with the day’s footage being replayed for activists on a portable monitor, refiguring video’s signature feedback loop as a dynamic political process.

It would be naive to think that video was ever simply a window onto the world. One might argue that another mode comes to dominate not long into the medium’s existence: video as a contestation with the world that video wrought, a world of too many images, too much information. Well before our age of post-truth bombardment, the television news broadcast is taken up as a form and a language to warp (Wolf Vostell’s Vietnam, 1968–71/72), deconstruct (Martha Rosler’s If It’s Too Bad To Be True, It Could Be DISINFORMATION, 1985), and parody (Marcelo Tas and Fernando Meirelles’s Varela in Serra Pelada, 1984). Dara Birnbaum’s Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission (1990) dislodges several fragments from the media repository produced by the Tiananmen protests of 1989, including the exact moment that the Chinese authorities cut off the access of TV news crews, and disperses them across a display—four small LCD monitors suspended from the ceiling and one larger, wall-mounted cathode-ray monitor switching among the four at random—that encourages a closer look at these partial views.

“Signals” repeatedly attests to the impossibility of grasping the big picture. While an installation like Birnbaum’s gets this across with rigor and purpose, this position can also settle into glib conventional wisdom, as in Frances Stark’s U.S. Greatest Hits Mix Tape Volume I (2019). Across six tablet screens, YouTube clips pertaining to what the accompanying text vaguely and confusingly calls “the history of US military intervention”—in Syria (1949), Iran (1953), Afghanistan (1979), Libya (2011), Ukraine (2014), and Venezuela (2019)—are paired with a Billboard chart-topper of the day. There is no prospect of sensing, let alone comprehending, the very different particulars of these situations (which range from coup d’etats to popular uprisings) or the nature of American involvement in each, since the point is to flatten everything into an atmosphere of distanced distraction.

In individual works—and in the show as a whole—the condition of inundation is both subject and strategy. The problem of our shattered attention spans, for which many would blame the proliferation of video screens, is not unrelated to the problem of exhibiting moving images in gallery settings. “Signals” confronts the viewer with no less than thirty-five hours of material. Certainly, a good number of these works do not ask to be experienced in full or from beginning to end. Temporal linearity is thwarted in the circular polyphony of Nil Yalter’s Tower of Babel (Immigrants) (1974–77/2016), and in the enveloping planetarium-like attraction that is Stan VanDerBeek’s reconstructed Movie-Drome (1964–65) (which actually deploys 16mm projection; the video aspect stems from the work’s unrealized potential as one node in a global “culture intercom”). But many single-channel pieces that require sustained engagement are presented as part of looped programs. Nearly forty videos—including important work by Ant Farm, Howardena Pindell, and Walid Raad, and lesser-seen standouts like Michael Klier’s Der Riese (The Giant) (1983), an eerie city symphony assembled from surveillance footage, and Yau Ching’s layered portrait of exile and dislocation, Flow (1993)—reside within the nine monitors that make up a viewing nook beyond the last gallery. Over two lengthy visits to the show, I could not help noticing that most museumgoers did not linger here for more than a few minutes, if at all. Anticipating the limits of spectatorial attention, MoMA has made many of these videos available for online streaming—a logical and meaningful decision that increases the reach of these works even as it effectively consigns them to a context of even greater overload and inattention.

The central propositions of “Signals” are inarguable. It is self-evident that video is everywhere, that it has transformed the world. The exhibition offers a compelling selective history of how this happened, cutting through multiple technological and geopolitical upheavals. What is less certain is video’s place in this transformed world: the view of the present that emerges here is diffuse and tentative, perhaps understandably so. It is hard to discern the shape of things as they change before our eyes, but it is also all too easy from our clouded, cluttered perspective to succumb to a kind of defeatist teleology. In accounts of both moving-image circulation and political film and video, one often detects a palpable longing for the before times: before the digital deluge in the former instance, before helpless despair and apathy in the latter.

At its most suggestive, “Signals” complicates these familiar chronologies, putting old work in productive conversation with new, as in the first gallery. Here one finds Gretchen Bender’s eternally relevant TV Text and Image (Donnell Library Center Version) (1990), with its sly block-lettered phrases (“SELF-CENSORSHIP,” “NO CRITICISM”) superimposed on live television broadcasts; the participatory playfulness of two early experiments in interactivity, Marta Minujín’s Simultaneidad en simultaneidad (Simultaneity in simultaneity, 1966) and Frank Gillette and Ira Schneider’s Wipe Cycle (1969/2022); and two recent works that chart different ways through and around the media flood. Martine Syms’s Lessons I-CLXXX (2014–18) consists of 180 30-second clips, fashioned from internet-sourced and original material and playing in randomized order, an epic collage of Black existence that uses its whiplash tonal shifts as a poetic organizing principle. Largely shot in a vertical aspect ratio and strikingly mounted in front of a floor-to-ceiling window at the show’s entrance, Tiffany Sia’s Never Rest/Unrest (2020) seeks to capture the 2019 Hong Kong protests as it was lived on the front lines, searching for an ethical vantage on events that are usually spectacularized and seen from the outside. The works in this space are disparate in their methods and registers, but in their complex entanglements with issues of immediacy, circulation, and (self-)representation, one senses a common question being addressed with urgency and imagination, the question of what it means for video to be political—and, as per Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, to be made politically. “Signals” shows us a multitude of answers, some more persuasive and consequential than others. In so doing, it also affirms that this is a question always worth asking.

Rosalind Krauss, “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” October, Vol. 1. (Spring 1976): 50-64.